Libertarian economics was always farcically out-of-touch with the realities of modern capitalism and it has proved as such in the case of Javier Milei, perhaps the world’s only libertarian head of state.

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and a prolific blogger.

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts’ blog

Last week US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent offered a $20bn swap line to Javier Milei’s government in Argentina and pledged to buy its bonds, as the Trump administration moved to shore up its ideological ally. The measures temporarily halted a rout in Argentine foreign exchange and bond markets triggered by the rapid depletion of the country’s foreign reserves as Milei sought to defend an overvalued currency.

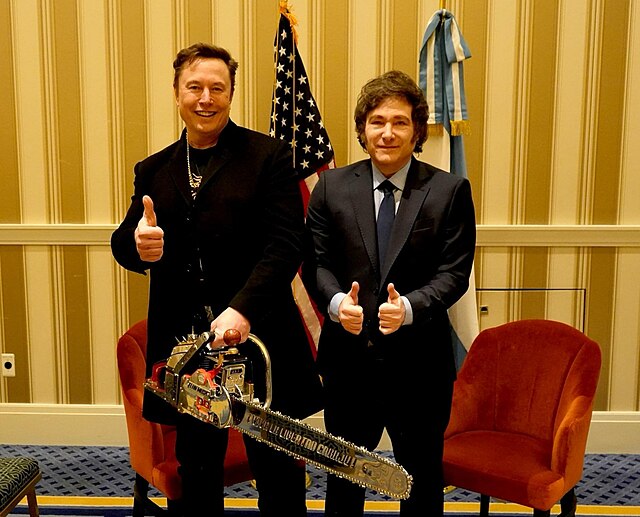

Over the past months, there has been wild optimism in financial markets and among mainstream economists and international agencies that Milei’s self-styled ‘chainsaw economics’ was working. Since taking office, Milei had taken a ‘chainsaw’ to government spending in welfare and public services and sacked thousands of public workers. As a result, the government budget was put into balance. Relying on record high IMF bailout funds to prop up the peso against the dollar, the Milei government has held the peso well above its real effective rate against the dollar in order to drive down Argentina’s horrendous inflation rate. It seemed that all was going well and all those the leftists and doommongers had been proved wrong – chainsaw economics was working.

Foreign investors and international agencies rushed to praise the free market economics aims and fiscal austerity measures of the Milei government as a successful alternative to ‘pink socialism’. With a pin of Javier Milei’s signature ‘chainsaw’ affixed to her jacket, during a press conference at the IMF spring meeting, IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva urged Argentinians “to stay the course” and back Milei at the upcoming legislative elections in October. “It’s very important that they don’t derail the will for change,” she said.

Then the OECD followed up the acclaim. In its report on Argentina in July, their worthy economists pronounced that “against the background of a difficult legacy of macroeconomic imbalances, Argentina has embarked on an ambitious and unprecedented reform process to stabilise the economy. Reforms have started to bear fruit, and the economy is set for a strong recovery. Inflation has fallen to levels not seen in years. The upfront fiscal consolidation process started in late 2023 has been instrumental to taming high inflation. Still, fiscal policy will require further fine-tuning to maintain fiscal prudence in the medium to long-term, while boosting potential growth.”

But then the chainsaw broke, triggered by the provincial elections in Buenos Aires, the largest region in Argentina. Milei’s party was expected to do well, based on the apparent success of his economic policies. But instead – disaster. Milei’s party lost by a staggering 14 points and the opposition Peronist party won 6 out of 8 electoral jurisdictions, including three it hadn’t won in 20 years. Milei’s party’s vote share fell in all eight districts and he lost by 10 points in the crucial first district, which is both a bellwether and a major economic hub for the province.

So, unlike the mainstream economists, the IMF and the OECD, the Argentine electorate were not so enamoured of the ‘anarco-capitalist’ Milei’s chainsaw economics, especially with the scandals that abounded in the Milei administration. His sister Karina, called “the Boss” by him and appointed General Secretary of the Presidency (the highest ranking non-Cabinet office in the executive branch), allegedly has been taking bribes from all and sundry (‘Karina takes 3%’, said Milei’s personal lawyer).

But more important for the voters of Buenos Aires province was that Milei’s chainsaw had destroyed jobs, good paying jobs, closed many businesses and forced people into ‘informal’work ie to make a peso anywhere they could. Milei claimed that the Argentine poverty rate has fallen under his government. And it is true that, as the inflation rate fell, the official poverty rate also dropped, to 31.6 percent in the first half of 2025. But the official poverty rate uses an outdated basket of goods to measure the cost of living. When that is updated (soon), the results could well be worse. Anyway, the huge cuts in government spending have led to high environmental risk, according to an index that considers the presence of pests, accumulation of garbage, and proximity to sources of pollution. Only 27% of homes are on paved streets, while 46% are on dirt roads. Half of households studied didn’t have a formal water connection and the figure was as high as 95% in some neighborhoods. Meanwhile, 63% were not properly connected to the power grid; and 41% of families rely on community kitchens, a figure that reaches 60% in some neighborhoods.

The Milei administration has defunded soup kitchens, accusing the social organizations that run them of being corrupt. So in Córdoba, a study found that 58% of families couldn’t afford the basic food basket in August. Half of households said they were skipping one of their daily meals, usually dinner. Two-thirds of Argentine children under the age of 14 are living in poverty. Multidimensional poverty (measured as income plus lack of access to key welfare factors) increased inter-annually from 39.8 to 41.6 percent and within that figure, structural poverty (three wants or more) rose from 22.4 to 23.9 percent. In sum, 25-40% of Argentine families are in deep poverty. And there has been a further increase in inequality. The top 10% of income earners now earn 23 times more than the poorest decile, compared to 19 times a year ago. The fall in income reached 33.5% year-on-year in real terms among the poorest decile, but only 20.2% among the richest. The gini inequality index has hit an all-time high of 0.47.

The Buenos Aires election ended the fantasy that Milei’s chainsaw economics and ‘free market’ policies were working. Capital, both domestic and foreign, suddenly realised that Argentines could soon vote out their hero and return the dreaded Peronistas to office. There was a run on the peso and the government and central bank was forced to use its scarce dollar reserves to try and keep the peso within the agreed exchange rate band with the US dollar, and so preserve the downward pressure on inflation. FX reserves dropped by more than $1bn a week, a rate that would soon have emptied the purse. Argentina has only $30bn in FX reserves. The government would not have been able to sustain the peso for much longer.

Source: Brad Setser

Milei may have balanced the government budget but the fiscal chainsaw did not deal with the continued weakness in the trade account. Under Milei, exports rose a little but imports also rose and income from exports flowed out. The monthly income deficit on the current account rose.

Source: Brad Setser

As soon as investors got hold of these FX dollars, they took them out of the country. In 2024, outbound investment totaled $3.3 bn (Argentines making portfolio investments abroad) and a $1.4 bn reduction in foreign portfolio investments into the country; so a total of $4.7bn outflow. In 2025 so far, another $2.6bn has left the country. This leakage of dollars is unsustainable.

Why was this happening? As the government aimed to maintain a strong peso to keep inflation falling, it had to use its dollar reserves to fill the income and investment gap. The strong peso may have driven down inflation as import costs fell, but it also meant that Argentine exports could not compete in world markets. And balancing the government budget did not deliver more dollars, but instead led to economic stagnation. Indeed, in the last few months, economic growth has petered out.

And ironically, even the artificially overvalued peso is no longer pushing down the monthly inflation rate – it’s been rising for the last three months.

Given the strong peso, Argentine industry cannot compete, so it is not investing at home. Over the past six quarters (from Q2 2024 to Q2 2025), the investment-to-GDP ratio averaged a new low of 15.9%. Investment rates are low because the profitability of capital invested in Argentina is at a record low.

Source: EWPT series and author’s calculations

And that’s the long-term story of Argentine capitalism. The economy has basically stagnated since the end of the Great Recession in 2008-9, particularly since the end of the global commodity prices boom in 2012. In the 13 years from 2012 to 2024, average real GDP growth was just 0.1%. Industrial output is falling and household consumption is stagnant, with retail sales falling. That’s hardly surprising when state salaries are down by 33.8% in real terms and Argentines are forced desperately to find work ‘informally’ as best they can.

According to the IMF, real GDP growth was expected to expand by about 5½ percent this year. That does not seem likely now. But such a rise in real GDP in 2025, even if achieved, would only take per-capita GDP back to the level of 2021, when the economy was emerging from the pandemic. Indeed, the per capita GDP index would still be well below its peak of 2011 (at the height of the commodity price boom), some 15 years ago.

The key to economic success in Argentina, as it is in all economies, is an increase in the productivity of labour through more investment in the productive sectors of the economy. All the previous IMF loans ended up being smuggled or invested abroad or used for financial speculation. Neither right-wing nor Peronist governments did anything to stop this speculative robbery of the Argentine people and resources.

As Argentine Marxist economist Rolando Astarita has pointed out, Argentina’s underlying weakness is related to technological and productive backwardness. Except in sectors where Argentina has natural advantages, such as energy from the Vaca Muerta region or the soy and corn complexes, productivity standards are low relative to international standards. Even in soybeans, wheat, and corn, productivity is below that of US producers. These differences are essentially due to differences in the level of investment in inputs and technology.

Source: Conference Board, TED2

Argentina’s foreign exchange reserves are lower now than they were in 2018, despite the IMF making huge loans since then. Former President Mauricio Macri borrowed $50bn that year — the fund’s biggest ever bailout — before his political downfall blew the IMF programme off course and hit the currency. Now after allowing for the IMF’s loans and liabilities such as a swap line from China, Argentina’s reserves have stayed heavily negative this year despite the IMF advancing more than half of a fresh $20bn bailout upfront.

Beginning in September 2026, large FX debt service obligations to private bondholders are coming due. Argentina has $95bn of dollar- and euro-denominated debt, against net reserves of just $6bn, according to Barclays. And it has to make $44bn worth of debt repayments between now and the end of Milei’s term in 2027. So Milei can ill-afford to use scarce foreign exchange reserves to prop the peso.

Also the US government will expect to get its $20bn back and the IMF ia already owed $57bn of credit outstanding to Argentina, or 46 per cent of the total. Will they be prepared to add more bad money after good?

So a devaluation of the peso looks increasingly inevitable. The peso needs to fall about 30 per cent to restore Argentina’s competitiveness and rebuild FX reserves, according to Capital Economics. But if that were to happen quickly, inflation would spiral upwards just as before Milei came into office. Thus the Trump admistation has stepped up (temporarily) to fix the chainsaw. “The plan is as long as President Milei continues with his strong economic policies to help him, to bridge him to the election, we are not going to let a disequilibrium in the market cause a backup in his substantial economic reforms.”

The aim now is for Milei to win the mid-term congressional elections and then devalue (gradually?) to boost exports and bring in dollars. But that will also mean the return of high inflation. So much for chainsaw economics.

Be the first to comment