Faced with the vicissitudes of neoliberal globalisation, the right-wing’s reactionary narrative may prove to be more potent with voters than the left-wing’s record of modest social justice.

Ben Wray is a freelance journalist and co-ordinator of BRAVE NEW EUROPE’s Gig Economy Project. He is co-author of ‘Scotland After Britain: The Two Souls of Scottish Independence‘ (Verso, 2022). He is based in the Basque Country.

The Spanish election campaign is rumbling towards its close, over before it really got started. It’s been a strange campaign, marked as much by its circumstances – an unbearable heatwave at the peak of summer – than anything either side has actually said or done.

The Ukraine war, the cost of living crisis, even the climate crisis – none of it has really captured the zeitgeist, least of all the war, which seems to be a complete political non-issue (the dead hand of a deadly pro-Washington consensus).

The election has heard much more about an armed militia that long ago ceased to exist, ETA, than the actually existing war in Europe. Indeed, one of the few debates that has broken out is the rights and wrongs of the use of an insult – “que te vote Txapote” – which refers to an ETA member who assassinated various Basque political figures in the ’90s*. You’ld call it surreal if it didn’t seem entirely fitting with our times, where perception and reality seem to have very little to do with one another.

“Que te vote Txapote” does actually provide as good a summary as any of the sort of campaign which the Spanish right-wing have fought, and which will probably win them the election. The PP and Vox are playing on the suspicion of many Spaniards that, after the Catalans tried to break up the country in 2017, the tail now wags the dog in Spain: a weak centre-left in PSOE is reliant on rebellious Basques and Catalans, aided by ‘communists’ (the Spanish left), to stay in power, and all that was good and wholesome about the country is being destroyed by this abomination, which they have dubbed “Frankenstein Government”.

In the minds of those who are moving towards the far-right, the 2017 Catalan wildcat referendum was a rupture, and Vox is the restoration. Not only will they destroy the regional parliaments which the independentists have used to build their power, they will also put LGBT+ people back in the closet, expel every last illegal migrant (especially the Muslim ones), and end all that talk about feminism and gender equality. Vox is your typical European far-right party which Spain had resisted for so long since the end of Franco’s dictatorship. It took the threat of Catalan independence to bring Vox to life.

What you won’t hear from Vox is any criticism of the real structural constraints on Spanish sovereignty. Like Georgia Meloni in Italy, if they do get into office they will be satisfied with picking on the most vulnerable and inflaming culture wars from the comfort of their ministerial cars. There will be no challenge to the international states, institutions and corporations which actually dominate Spain in 2023: the US, the EU, Nato, the WTO, Blackrock, Facebook, etc.

You could say Europe’s far-right nationalists lack ambition, but their dream isn’t actually national sovereignty: it’s to capture the EU machine for itself. That’s an aim that – as they continue to rack up election successes across the continent – looks far more realistic than ’Spexit’ or ‘Italexit’ right now.

If Vox get ministers, they will be constrained within a PP dominated government which is led by a leader, in Alberto Feijóo, who is on the party’s moderate wing. He will ensure Vox can’t exercise control over the big levers of state, in the same way as Pedro Sánchez kept Podemos ministers away from the most powerful ministries. Vox’s real role is to push back against the PP when it seeks to reach into the political centre-ground, as Feijóo would like to do.

Indeed, the PP leader has even said he will not even undo the most significant structural reform of the PSOE-Podemos coalition government: the labour reform of Yolanda Díaz, leader of the Spanish left’s new umbrella coalition, Sumar. The labour reform passed due to a buffoonish PP representative voting in error, but Feijoo now says that it is “substantially good”.

“Among my proposals, modifying the labour reform is not there,” he told journalists in Brussels.

It’s noteworthy that Feijoo made this announcement from the heart of the EU. It was the EU that had demanded Spain do something about its exceptionally high rate of temporary labour contracts, the highest in Europe after Poland. Bringing the Spanish labour market into line with European norms was a precondition for Spain receiving its full tranche of ‘Next Generation EU’ funds, as well as reforms to its pension system. The fact that EU funding was tied to undemocratically mandated reforms did not raise even a hint of complaint from PSOE or Podemos.

The labour reform itself has succeeded in delivering a quick rise in the number of workers getting indefinite contracts, which does benefit the poorest workers the most. On the otherhand, the pro-business side of the law – which makes it easier to sack workers — has not been tested yet by an economic downturn.

In any case, the labour reform is not the only change which the left can point too as a victory of the past three and a half years. Others include a 47% increase in the minimum wage, free public transport journeys, a temporary windfall tax on profits, a deal with the EU to cap gas prices (jointly with Portugal) and a housing law to restrict rent increases.

All of these measures have undoubtedly contributed to inflation falling faster in Spain than any other EU country. It is now below the 2% target central bankers bang on about so much, an inflation rate which German ordoliberals would kill for. Spain looks like one of the few beacons for social democracy in Europe, which is why even Gordon Brown is chipping in with his support for Sánchez.

Brown fails to mention that the PSOE-Podemos coalition government has relied on the votes of Basque and Catalan independence parties to deliver many of its key reforms. More importantly, while Spain may be doing well in relative terms, voters don’t generally think about whether they are doing less bad than other countries, they think in terms of whether they are poorer or better-off than they were before. On this metric, working class Spaniards are going backwards, while the rich are still getting richer.

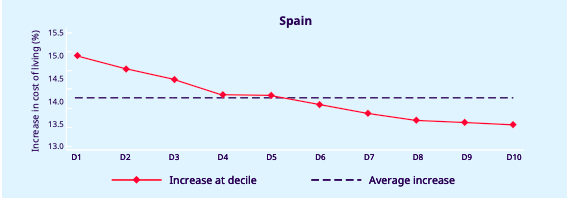

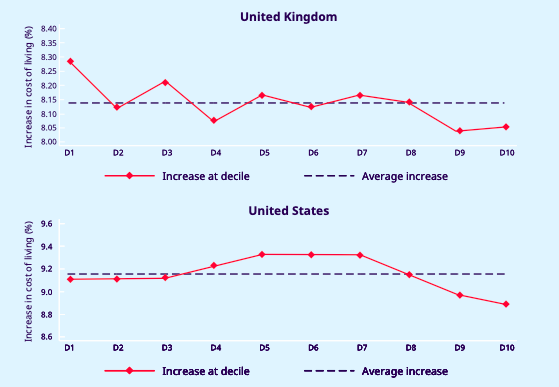

Indeed, an ILO report has found that the poorer you are in Spain, the larger % of your income you’ve lost as the cost of living has risen.

This compares badly even with countries like the UK and the United States.

On poverty, the latest figures show that the percentage of the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion decreased to 26% in 2022, from 27.8% in 2021, a marked improvement. But the year that the coalition government came to power, in 2019, the figure was basically the same as now (26.2%). The number of people who make ends meet with great difficulty has actually risen, from 7.8% in 2019 to 8.7% in 2022.

None of this is to say that the coalition government has not delivered some decent reforms. The point is that the Sánchez’ government has done more than most, but that still has not been enough to shield the working class from the vicissitudes of neoliberal globalisation. And that reality has an effect in elections, as it’s difficult to tell a compelling story about social justice – a story that is better than the right-wing’s one about ‘Frankenstein government’ – if people don’t feel it.

One could argue that the coalition government has faced difficult circumstances, with a pandemic and cost of living crisis, but crisis is the new normal. The left either learns how to deliver during crises or doesn’t deliver at all.

Moreover, there’s lots of reasons to believe that if PSOE and Sumar are able to win another four years of coalition government against the odds, the fiscal circumstances will be more difficult than in the previous three and a half years. Fiscal space grew under the PSOE-Podemos government, with public debt to GDP rising from 100% in January 2020 to 113% at the start of 2023. With fiscally-conservative Germany dominating the debate on new EU public debt rules, austerity is more likely than more fiscal expansion.

There are still good reasons to believe that the left might win on 23 July. But this may just be a reprieve from the clutches of reaction, rather than its defeat. The times we live in require a left politics which can do more than not quite holding back the tide.

*This has been edited after publication for accuracy. The original referred to the assasination of just one Basque councillor

Thanks to many generous donors BRAVE NEW EUROPE will be able to continue its work for the rest of 2023 in a reduced form. What we need is a long term solution. So please consider making a monthly recurring donation. It need not be a vast amount as it accumulates in the course of the year. To donate please go HERE.

Be the first to comment