Giant investment firms now dominate the corporate world. Is it time to rein them in?

Benjamin Braun is a political scientist at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies in Cologne.

Adrienne Buller is policy director of Labour for a Green New Deal

Cross-posted from Open Democracy

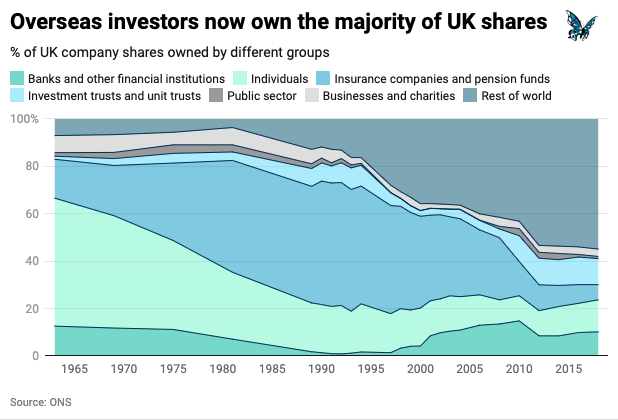

In the space of just a few decades, the ownership landscape of the global economy has been radically transformed. For much of the past half century, our large corporations were primarily owned by individual shareholders, insurers and pension funds. Today however, they are overwhelmingly owned by asset managers – financial intermediaries who invest on behalf of beneficiaries such as pension holders or wealthy individuals.

Crucially, this growth has been accompanied by an enormous concentration of assets and power within the asset management industry itself. BlackRock, the largest manager worldwide, controls $9 trillion in assets; its closest competitor, Vanguard, controls $7 trillion. Together, that’s enough to own every company listed on the London Stock Exchange, four times over. With ownership comes voting rights to shape corporations’ actions on everything from the climate crisis to working conditions.

From snapping up vast real estate portfolios to administering the Federal Reserve’s COVID-19 corporate bond purchase programme and advising on the EU’s sustainable finance legislation, BlackRock’s power has grown enormously during the pandemic. Indeed, the extent of its influence in the US led two Bloomberg journalists to describe BlackRock as a ‘fourth branch of government’. These giant asset managers are now among the most powerful companies in the world, yet most people have never heard of them.

In a new report published by Common Wealth this week, we tracked this concentration of ownership in the 350 largest corporations in the UK (the FTSE350) over the past 20 years, asking what it means for the governance of ‘UK PLC’. We found that a full fifth of the total value of the FTSE350 is controlled by just ten investors. While this may not seem enormous at face value, compare it to a simple analogy: if these corporations were a small country, 20% of its entire voting power would be controlled by just ten citizens among thousands – hardly a democratic arrangement. Then imagine those same ten citizens also had a similar degree of control in hundreds if not thousands of other countries, and the picture becomes less democratic still.

This accelerating concentration is coinciding with the unprecedented rise of fully diversified ‘universal’ portfolios, wherein managers are invested in assets across all geographies, industries and asset classes. Moreover, the players dominating the industry are largely ‘passive’ investors, meaning their portfolios are constructed based on pre-determined indices, often from third party providers, rather than the discretion of scrappy portfolio managers looking to ‘beat the market’. This high degree of indexation means investors cannot, as a general rule, exit investments in individual firms – whether as punishment for undesirable behaviour or otherwise.

In light of these quiet but profound shifts, the UK has entered a new era: the age of “asset manager capitalism”. In contrast with the image of the activist shareholder, on which the prevailing ‘shareholder primacy’ regime of corporate governance is often justified, asset manager capitalism is defined by a structural disincentive for shareholders to be concerned with the actions and performance of companies in their portfolio.

Instead, managers are motivated by growing their asset pool and market share, even going so far as to offer funds with no fees in an effort to capture more of the market. Although financial firms offering products for free seems unthinkable, the move – spearheaded by the US giant Fidelity – is entirely congruent with the fundamental drive of these entities: accumulate, accumulate, accumulate.

The result is that we are sleepwalking into an economy in which a handful of enormously powerful actors not only have decisive influence over the actions of the corporations in which they hold shares – they also have enormous power over the economy writ large.

In theory, the position of firms like BlackRock as long-term, universal shareholders with considerable stakes across the whole economy should make them uniquely attendant to systemic risks like the climate crisis or widening inequality. Yet independent analysis from ShareAction, InfluenceMap, Sarasin & Partners, Friends of the Earth and others has repeatedly found that the largest asset managers are failing to throw their weight behind these issues, and have routinely voted against or abstained on shareholder resolutions on everything from supply chain deforestation to climate targets, to exorbitant executive pay packets.

At the same time, pressure on corporations to ‘disgorge the cash’ to shareholders has helped reorient companies toward prioritising these interests above all other stakeholders, whether labour or the environment. In 2020, aggregate dividend payouts by the FTSE350 companies represented some 90% of pre-tax profits, despite approximately 80 firms not delivering a dividend in the pandemic year. This reflects more than two decades of upward drift in shareholder payouts – increasingly paid for with record levels of corporate debt. Over the same period, productive investment declined substantially.

In aggregate, this type of extractive behaviour undermines efforts to build an inclusive, low-carbon economic future by squeezing the labour share of profit and undercutting the investment needed in decarbonisation or changes to unsustainable and unjust supply chains. The rise of asset manager capitalism therefore marks a new era of corporate governance which has important implications for how our economy operates – and in whose interests.

However, efforts to overcome the extractive and unequal nature of the corporate economy all too often remain stuck in the past, striving to dismantle a structure that no longer exists. Today, comparatively little productive capital is raised on the stock market, and the rise of indexation means that capital is no longer ‘efficiently’ allocated by the invisible hand of aggregate shareholder behaviour. We must therefore ask the question: what are shareholders for?

The corporation is a site of immense productive and organisational capacity, but its extraordinary privileges – as well as those given to shareholders – are publicly endowed. They are not fixed or natural. Going forward, the corporation needs to be reclaimed as a social institution that supports generative enterprise and collective endeavour. In the context of the climate crisis, profound inequality and increasingly entrenched exploitation in global supply chains, this need is urgent.

We can start by reckoning with the role and influence of BlackRock and other asset managers in our economy, and designing strategies to challenge and democratise corporate power.

Be the first to comment