AAP/Boris Jancic, CC BY-ND

Christoph Schumacher, Massey University

New Zealand’s first “well-being budget” has landed, prioritising well-being over economic growth. So how is it different to any budgets that we have seen in the past?

The government has moved away from GDP as a sole indicator of our nation’s prosperity. It justified this move because GDP is a good measure of economic growth but doesn’t provide us with any information about the quality of the economic activity or the well-being of people.

GDP doesn’t tell us whether people are struggling to meet basic needs or if everyone has access to health care and education. Neither does it give insight into whether people have social connections, feel safe, are happy and feel proud to live in New Zealand.

A nation’s well-being

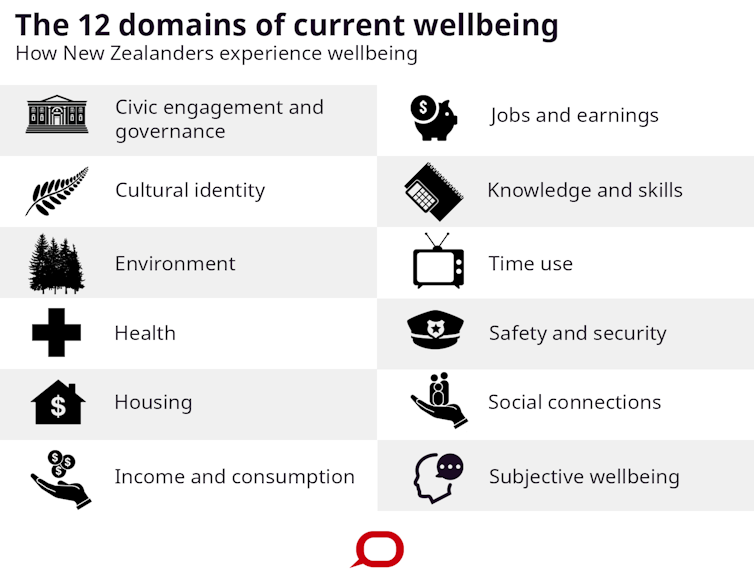

In order to quantify these social concerns, the New Zealand government has decided to take a more holistic approach to measuring how well we are doing as a nation. It developed the Living Standards Framework (LSF) as a practical set of meaningful well-being indicators to guide policy advice. Overall, there are 12 domains that describe and capture how New Zealanders experience well-being.

At a first glance, the government is doing something different. But given the close link between well-being and economic growth, it might simply be called budget 2019. Without a well functioning economy, we don’t have the resources to spend on well-being. And, if you look at the key dimensions of the LSF – health, housing, income, environment, employment, education and safety – you’d be right to think that they are the same focus areas we’ve seen in previous budgets.

So, does the budget earn the government’s well-being title? To answer this question, we have to check if spending matches up with the domains of the LSF. This is not straight forward, as some of the domains have intangible components. For example, while it is relatively easy to see if funds are allocated to some of the domains, it is less straightforward to determine the impact of the domains of civic engagement, cultural identity, time use, social connections and subjective well-being.

Investment in mental health

In December last year, finance minister Grant Robertson announced five main spending areas: creating a low-emission economy, supporting social and economic opportunities, lifting Māori and Pacific incomes and opportunities, reducing child poverty and supporting mental health. These priorities are not substantially different from priorities of previous budgets, but they cover the key LSF domains.

Let’s now take a close look at the actual budget figures. Mental health is getting NZ$1.9 billion over five years – its biggest investment to date with NZ$200 going into new mental health and addiction facilities.

Whānau Ora, a programme that puts Māori families in control of the services they need, gets an NZ$80m injection over four years. There is NZ$1.7b going towards fixing hospitals and child welfare is receiving funds, as promised, with NZ$1.1b is going to the child welfare agency Oranga Tamariki. An additional NZ$200m will be spent on improving the welfare system and NZ$320m will go towards tackling family and sexual violence.

Housing First also gets a boost with NZ$197m from within the mental health budget. This should help tackle homelessness but it is not enough to address the housing shortage in our main cities.

Conservative spending on security, education

Safety and security receive a relatively conservative injection, with corrections receiving NZ$183m and justice NZ$71m. There is also NZ$98m being spent on trying to break the cycle of Māori re-offending and imprisonment.

There will be NZ$1.2b going into new schools and classrooms over the next ten years, with a further NZ$95m towards increasing the number of teachers. But looking at the current and ongoing teacher strikes, this doesn’t appear to be enough to meet the demands and expectations of teachers.

Primary and secondary teachers took to the streets for a

Primary and secondary teachers took to the streets for aThere is little in the budget targeting income and employment other than a NZ$530m package to index main benefits to wage growth from April 2020. This means that benefit payments will rise in line with wages, not inflation.

There is a surprisingly large NZ$1b injection into Kiwirail to revitalise rail networks. The benefits of this in terms of well-being are not yet clear.

The government delivered on most of its pre-budget promises and covers a variety of its specified well-being measures. But is it a well-being budget? Yes, but the real difference to other budgets remains to be seen in terms of whether the associated social development initiatives will actually raise the living standards of all New Zealanders.

Well-being happens at the front line in people’s homes and workplaces. Time (and next year’s numbers for the Living Standards Framework domains) will tell if the money allocated translates into a real improvement to people’s perceived sense of well-being. Only then will it have justified its new title.

Christoph Schumacher, Professor of Innovation and Economics, Massey University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Be the first to comment