Member states play a hugely important role in EU decision-making, but too often they act as middlemen for corporate interests. This new report combines case studies, original research, and analysis to illustrate the depth of the problem – and what you can do about it.

Cross-posted from Corporate Europe Observatory

The member states of the European Union are intimately involved in, and responsible for, the EU’s laws and policies. Governments set the EU’s strategic direction, are closely involved in both the drafting and implementation of EU rules, and have final sign-off on all EU legislation. “Captured states: when EU governments are a channel for corporate interests” focuses on the democratic deficit that sees too many member states, on too many issues, become captured states, allowing corporate interests to malignly influence the decisions they take on EU matters. Instead of acting in the public interest of their citizens and those in the wider EU, they often operate as channels of corporate influence.

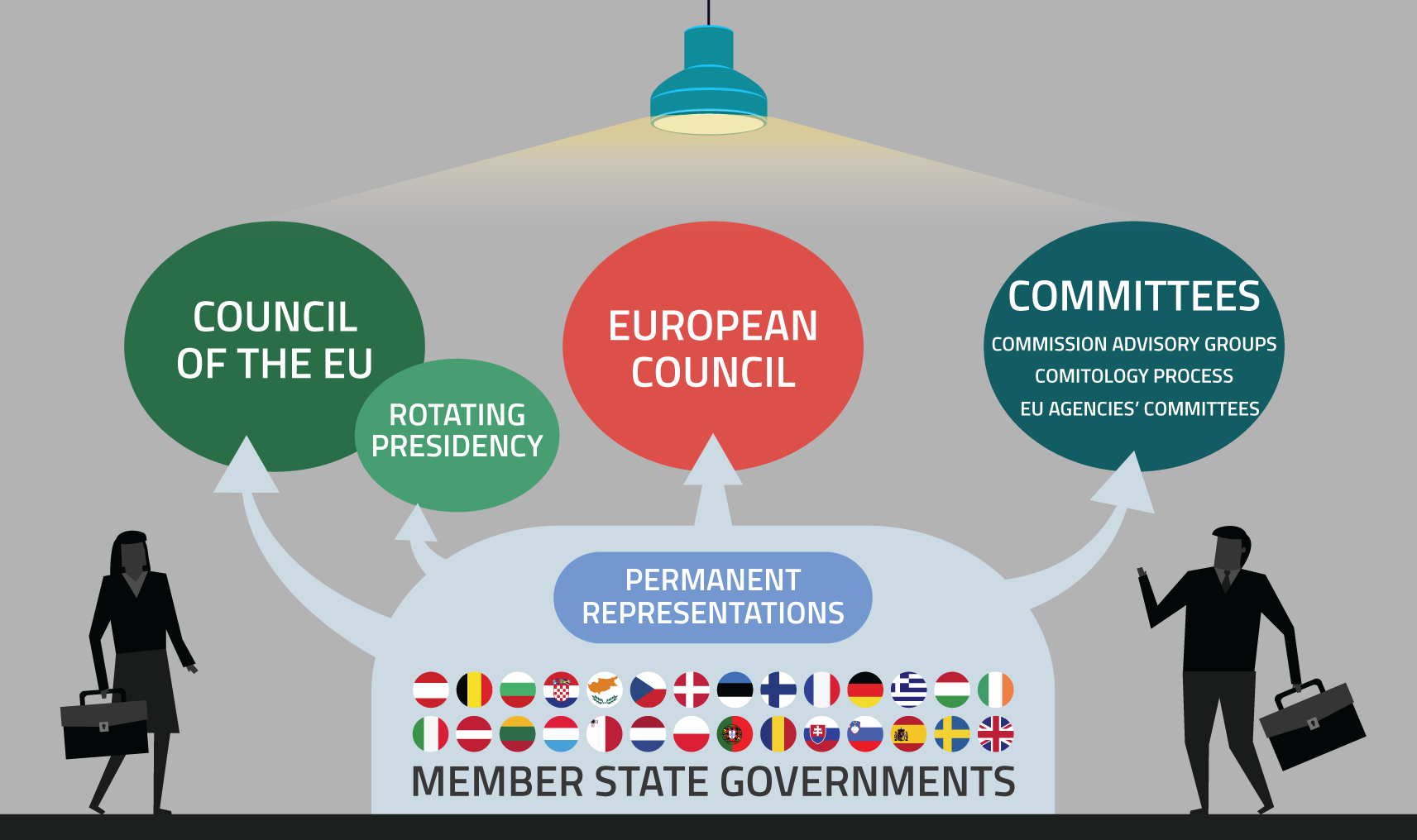

Many of the ways in which member states feed into EU decision-making are not well-known, and are neither transparent nor commonly studied. The report breaks new ground by providing an overview of how member states act as middlemen for corporate interests with a focus on the following European institutions:

|The Council of the European Union where member states’ ministers and officials input into EU law-making and policy-making. The six-month rotating presidencies of the Council of the EU also feature here.

|The European Council where heads of government of EU nations gather regularly for summits and to make pronouncements on the EU’s broad future direction.

|The EU’s committee structure which provide member states with key seats at the table to discuss the technical and scientific detail of proposals and their ultimate implementation.

The report’s key findings are:

1. Corporate interests, including EU and national-level trade associations as well as multinational corporations, are really dominant in lobbying member states on EU decision-making and they have numerous successes to show for it.

|Elite corporate lobbies target the European Council of member state leaders, with access that NGOs and trade unions cannot match. For example the regular meetings of the European Round Table of Industrialists bring together 50 bosses of major European multinational companies with the leaders of France, Germany, and the Commission President.

|Rotating presidencies of the Council of the EU provide a key target for corporate lobbies. This report shows, for example, how the 2016 Dutch Presidency promoted both the interests of the arms industry, and the corporate-designed concept of the ‘innovation principle’ in EU decision-making which undermines precautionary approaches. Additionally, corporate sponsorship of rotating presidencies now appears to be standard.

|The EU’s complex and opaque committee structure benefits corporate lobbies with the resources and capacity to influence the final outcomes. The decision-making on the licence renewal of the pesticide glyphosate and the safety of the whitening agent titanium dioxide both demonstrate the reach and staying power of the chemicals’ industry lobby.

|Brussels-based lobby consultancy firms provide specific services to corporate lobbies aimed at influencing member states, such as Fleishman-Hillard’s annual gas forum for member state officials, organised for trade association GasNaturally, a lobby forum for major gas companies such as Shell, Total, and RWE.

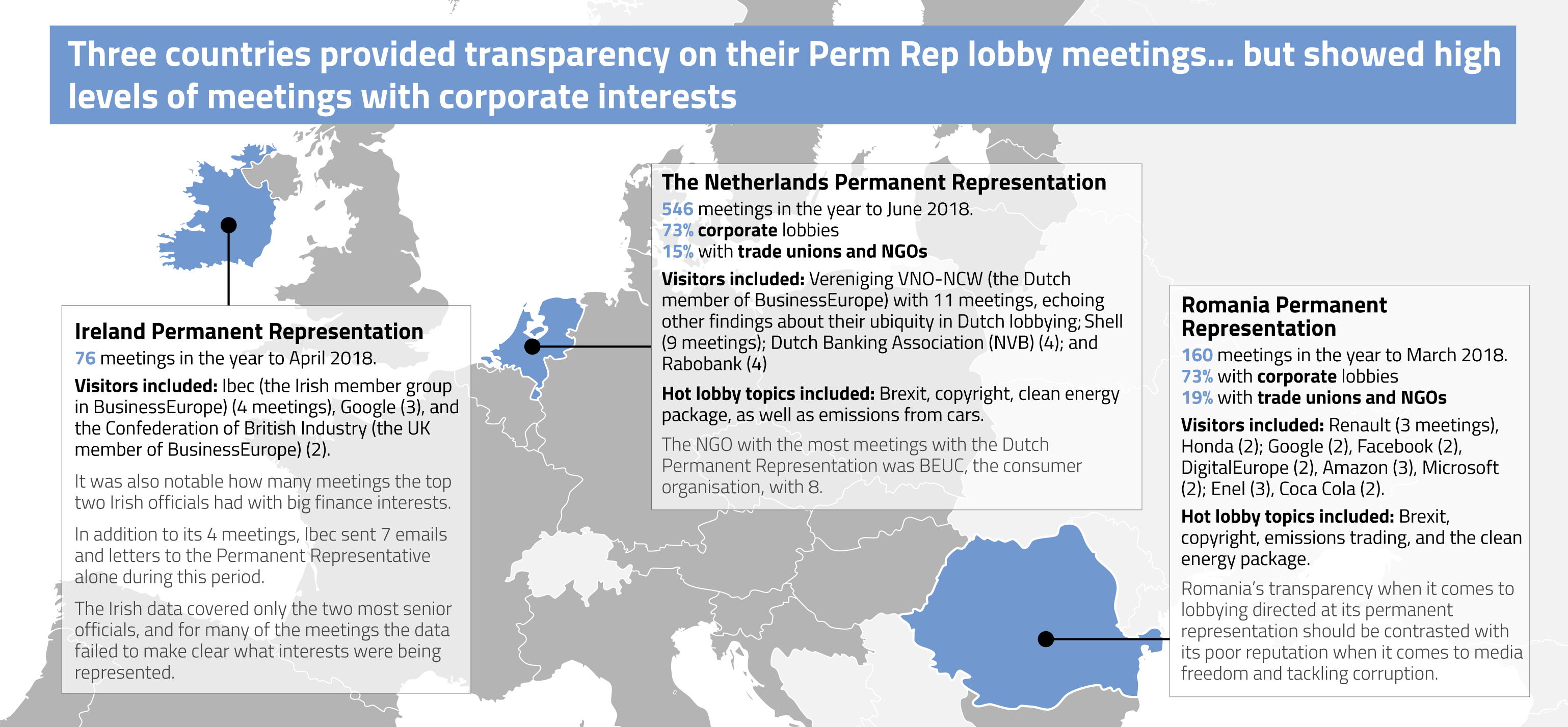

|Where data is available, corporate interests held the clear majority of lobby meetings with officials working at the permanent representations of member states. The Dutch Permanent Representation’s officials held over 500 lobby meetings between June 2017 and 2018 and 73 per cent of these were with business interests, and only 15 per cent with NGOs or trade unions.

2. As a consequence, there is a massive asymmetry of influence on member states’ EU decision-making as civil society groups cannot match the privileged access and far greater lobbying capacity and resources of the corporate sector.

3. Member states and national corporate lobbies have developed a symbiotic relationship whereby the national corporate interest has – wholly wrongly – become synonymous with the national public interest as presented by the relevant government in EU fora. Extreme examples include the influence of the car industry on theGerman political establishment (and the negative impact of this on EU climate and emissions’ regulation); Spanish telecoms giant Telefónica, whose closeness to the Spanish Government ensured its demands were absorbed and promoted; the state-owned coal industry which leads the Polish Government to be such a climate pariah; and the City of London, which can count on the UK Government to back its demands for the lowest possible financial regulation.

4. At the EU level, member states have collectively absorbed some corporate agendas and adopted them as part of the EU-wide agenda, such as on economic governance (strict fiscal rules and austerity) and investors’ protection in trade treaties (allowing corporations to sue states for billions in compensation when governments act to protect their people and the planet).

5. Some member states proactively reach out to corporate lobbies. Rotating presidencies represent a particular opportunity for a member state to actively champion a pet project, issue, or national industry. The recent Austrian Presidency organised a high profile event for EU ministers at the premises of its key national steel producer voestalpine, even launching an initiative to promote ‘green hydrogen’ (which will most likely give a boost to fossil fuel gases) signed by member state ministers.

6. A number of commissioners from the Juncker Commission appear to have a bias towards corporate interests from their own member states when it comes to lobby meetings, providing business with another potential ‘national’ channel, on EU decision-making. Commissioners Oettinger, Hill (who left the Commission in July 2016), Cañete, Hogan, and vestager have all held a disproportionately large number of meetings with corporate lobbies from their own country.

7. Complex EU decision-making procedures, a lack of transparency, the exclusion of citizens in decision-making at national level on EU matters, and generally weak national parliamentary mechanisms, have combined to create an accountability and democratic deficit, which corporate lobbies are happy to take advantage of. As just one example of the transparency problem surrounding the way in which member states participate in EU affairs, only 4 out of 19 permanent representations (Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, Romania) provided some transparency regarding their meetings with lobbyists. The others remain totally non-transparent.

Contemporary nationalist rhetoric argues that a strong EU is imposing rules and regulations on nation states and sometimes it suits member states to play up to this narrative and blame the EU for decisions which are unpopular at home. However, blaming the EU ‘apparatus’ alone is far too simplistic.

Too often, member state governments, acting individually or collectively, are a bastion of corporate influence on EU decision-making. The risk of corporate capture of some member states, on some EU dossiers, is very high, undermining democracy and the public interest. And it is getting worse.

With this report, we hope to alert civil society and decision-makers to the threat that corporate lobbies, influencing member states, have on EU decision-making. Our full report makes suggestions for what you can do and our recommendations set out some initial steps to start to counter this corporate influence. They include:

1. Member state governments must adopt national rules and cultures which reduce the risk of corporate influence on EU decision-making, including an end to privileged access for corporate lobbies and full lobby transparency.

2. Member state parliamentary scrutiny and accountability on government decision-making at the EU level must be strengthened. This should include both pre-decision scrutiny and post-decision accountability.

3. Urgent action is needed by the EU institutions to tackle the democratic deficit in how they operate. These will require reforms of the ways of working of the Council of the EU, the European Council,and the European Commission’s comitology process and advisory groups.

4. We urgently need new models for citizens to both find out more about, and have a say on, the EU matters with which member states are tasked with deciding. These could include participatory hearings, at the national level, on upcoming pieces of EU legislation; on-line consultations; and more.

Download the full report.

Be the first to comment