Regional elections in Umbria on 27 October produced a clear victory for Matteo Salvini and the Italian right. Daniele Albertazzi and Mattia Zulianello write that with the Five Star Movement and Democratic Party failing to pass their first electoral test since forming a government together in the summer, Italy could soon be heading for a new general election.

Daniele Albertazzi is a Reader in Politics at the University of Birmingham.

Mattia Zulianello is a Research Fellow at the University of Birmingham.

Cross-posted from LSE EUROPP

The Italian right scored a stunning victory in the regional election that took place in Umbria on Sunday 27 October, casting doubt on how long the current government backed by the left and the Five Star Movement (M5S) can survive. The winning candidate for the regional governorship came in the shape of Donatella Tesei, a League senator who, besides her own party, also enjoyed the backing of Forza Italia (FI), and Brothers of Italy (FdI). Tesei’s victory over her main rival, Vincenzo Bianconi, was overwhelming: she gained 57.5% of the vote vs. his 37.5%.

Despite the region having always been governed by left wingers since the institution of regional administrations some fifty years ago, the writing for the ruling centre-left Democratic Party (PD) had been on the wall for some time. Not only had the League gained an impressive 38.2% of the vote here at the 2019 European elections, but the PD’s reputation had taken a hit when the previous governor, a member of the party, had to quit due to a scandal. What had not been expected, however, was the scale of the defeat, particularly since the PD had reached an agreement with the populist M5S that they would both throw their weight behind Bianconi’s candidature for the governorship.

Winners and losers

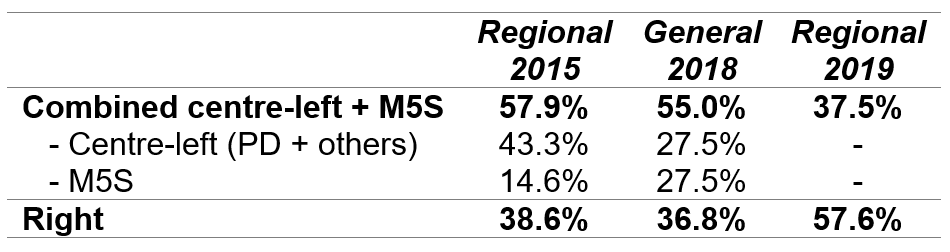

An early sign that something of note was going on was provided on the day by the 9% increase in turnout, compared with the regional elections of 2015 (64.4% vs. 55.4%). This is yet another confirmation that, when people believe they can bring about change, they do participate in larger numbers. Interestingly, the right swapped places with the PD/M5S alliance percentage-wise, as it secured almost exactly the same percentage of votes that its opponents had gained in the previous regional election (see Table 1).

Table 1: Electoral results in Umbria for the major Italian coalitions

Note: The table shows the combined vote share for the centre-left (the Democratic Party – PD / others) and the Five Star Movement (M5S). These parties ran together in the 2019 regional election in Umbria, but did not run together in the two earlier elections.

Note: The table shows the combined vote share for the centre-left (the Democratic Party – PD / others) and the Five Star Movement (M5S). These parties ran together in the 2019 regional election in Umbria, but did not run together in the two earlier elections.

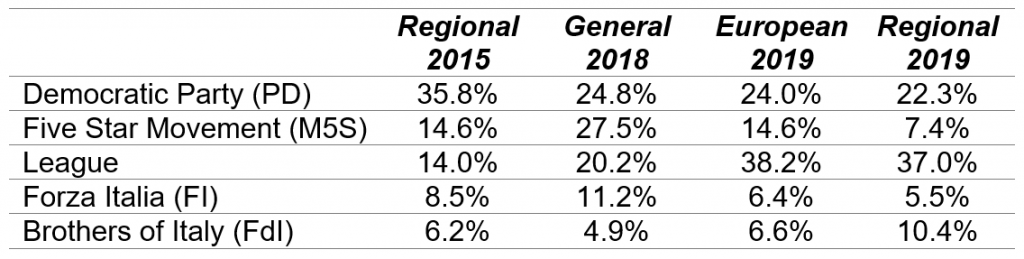

Other interesting trends emerge as one considers the performance of individual parties. The League, which had become the largest party at the 2018 general election, confirmed its status by gaining roughly the same percentage of votes it had secured in the 2019 EU elections: 37% on Sunday versus 38.2% back in the spring. In the meantime, FdI (a party many commentators regard as extreme right) also had a very good night, doubling its support from 2018 (see Table 2), with Berlusconi’s FI limping home on 5.5% of the vote – a nightmare for what had once been the dominant component of the right-wing coalition.

Table 2: Electoral results in Umbria for the major Italian political parties

Note: Compiled by the authors.

Note: Compiled by the authors.

If Berlusconi may not have felt like cracking open the prosecco, the right’s opponents had even less reason to celebrate. This was particularly true of the M5S, as it clinched a mere 7.4% of the vote vs. the 27.5% it achieved in 2018. At 22.3%, the PD’s vote share was not dissimilar to what it had gained in the general election last year and the EU elections this year, hence the main problem for the party was the loss of the governorship and the scale of Matteo Salvini’s triumph.

The right had a good night, so what?

If the success of the right is undeniable, the reasons why this should matter beyond the borders of Umbria may not be immediately apparent, given that only 700,000 people were entitled to vote in this election. In fact, the composition of the losing coalition is the issue here, insofar as it closely mirrored the one governing the country.

Salvini’s League decided two and a half months ago to walk out of the government it had formed with the M5S, but the party failed to trigger a general election. PM Giuseppe Conte managed to stay on, supported by the PD and M5S. Now that these two parties have resoundingly failed to pass the first electoral test they sat together in Umbria, Salvini will inevitably agitate to finally get the election that eluded him in the summer, claiming that the government does not enjoy the support of Italians. Indeed, if a defeat in Umbria sets in motion a series of similar defeats across Italy, an election may well become inevitable. More specifically, if the right wins the election coming up in January in the much larger Emilia-Romagna region – another former stronghold of the left, but one that has not been plagued by scandals – then the momentum could become unstoppable for fresh elections to take place next spring.

The scale of the M5S’s defeat clearly indicates that its decision to integrate into the political system and abandon its isolationist strategy has largely been a failure. The M5S may be one of many populist parties in Europe that are integrated into the coalition game, but unlike many of its counterparts it has lost its credibility as it has started taking on governing responsibilities. Hence, faced by a rapidly weakening party, the most “League-friendly” M5S deputies and senators may have a strong incentive to jump ship and join the League’s group in Parliament, possibly leading to Conte losing his majority. This swapping of t-shirts is hardly unusual in Italy. There are also those within the M5S who see an early election as an opportunity to get rid of “the old guard”– starting with their high-profile leader and current Foreign Minister, Luigi Di Maio. They would be happy to regroup in opposition, if the prize were a fundamental shake-up of the party.

As for the left, unity is obviously not their forte either – the PD recently suffered yet another split when former PM Matteo Renzi left to create his own personal, centrist party. It is impossible to guess for how long Renzi will want to be seen as being on the side of a “coalition of losers” by providing support to Conte (which the PM needs), if indeed more defeats start pouring in. In this case, Renzi may view an early election as the lesser of two evils, to at least establish his party as the novelty of the contest – with an eye to eroding the PD’s support. After all, it was not lost on anyone that Renzi avoided to turn up during the last days of the campaign in Umbria, as rumours about the growth of the right started intensifying.

The result means that the League, once a regionalist actor territorially concentrated in the North of the peninsula, is consolidating its status as a state-wide party, and that Salvini will continue to lead the right for the foreseeable future. Opposing him will be two parties that at present look directionless. If the right can repeat its Umbrian feat in the forthcoming regional elections – a much harder task in Emilia-Romagna – then the election on Sunday may come to be seen as the beginning of the end for the second Conte premiership – and indeed possibly for the M5S as we know it.

Be the first to comment