The Odra disaster is just one of many cases across Europe where exploitation of rivers is still prioritised over restoration.

Ewa Leś is a biologist with a background in environmental law. Her work focuses on freshwater security, water policy, water democracy building, and water conflicts. She is the founder of the River University, and co-founder of the Polish Save the Rivers Coalition (2016).

Cross-posted from the Green European Journal

Jumping in headfirst can be risky, especially into unknown waters. This time, however, we know the waters. They are our waters. Across Europe and around the world, rivers are under serious stress from pollution, hydromorphological pressure, and climate change. By neglecting to manage and maintain the health of our river systems, we are jumping headfirst into the unknown.

Once free-flowing water bodies full of life, Europe’s rivers are dying. The facts are alarming and are the result of human activity. A majority of European river basins are not on track to meet the goals of the EU Water Framework Directive. Introduced in 2000, this crucial piece of legislation was designed to protect the integrity and health of river systems. To safeguard all aspects of their life, rivers must flow naturally and with continuity. Yet in Europe, there is an average of 0.74 barriers for every kilometre of watercourse. Even more strikingly, in Poland, there is a weir every 2.28 kilometres. Imagine how a river feels to be tangled, immobile, and unable to move freely.

The situation of Polish rivers is particularly dire for other reasons too. Over 90 per cent of rivers in the country are in bad condition and in urgent need of restoration. Poland was in the spotlight in 2022 due to the ecological catastrophe of the Odra, its second-largest river after the Vistula. Industrial discharges of salt waters on the Polish side of the Odra basin, in combination with high levels of nutrients and drought, enabled toxic algae to bloom, causing devastating environmental and economic damage that spilled from Poland into Germany. It was a sharp reminder of how rivers and the effects of their mistreatment know no borders. 97 per cent of the Baltic Sea area suffers from eutrophication due to excessive inputs of nitrogen and phosphorus via inland waters from the surrounding countries.

Across the border into Ukraine, water has even become a weapon of war. In June 2023, Russian aggression took on a new dimension with the destruction of the Kakhovka dam. The explosion caused an immediate, uncontrolled, and massive water discharge from the dam’s reservoir, the largest in Ukraine in terms of water volume. The result is a man-made disaster across the middle and lower Dnipro River catchment, the consequences of which will be felt for decades.

Though the health of our rivers is crucial for water security, the plans and actions necessary to preserve or restore it are not in place. Water policy, and especially its implementation, is becoming increasingly urgent. Are we jumping in headfirst?

The EU’s proposed Nature Restoration Law is a potential game changer for Europe’s rivers. Put forward by the Commission in 2022, it aims to contribute to the long-term recovery of damaged nature across the EU’s land and sea areas, and to achieve EU climate and biodiversity objectives.

After the legislation narrowly survived a conservative attempt to sink it, its final details are now being negotiated by the EU Parliament, Council, and Commission. The agrifood lobby that spearheaded the push against the law is the same that holds significant responsibility for the pollution of Europe’s rivers. The proposed law has as its targets the restoration of almost all nature habitats in need (in particular riverine and alluvial habitats) and of 25,000 kilometres of free-flowing rivers, as well as the transition of agriculture towards more sustainable practices (including extensive wetlands rewetting, which would reduce the presence of agricultural pollutants in rivers).

Troubled waters in Poland

When it comes to rivers, the two restoration priorities are allowing them to flow freely and preventing pollution. In 36 European countries, there are at least 1.2 million transverse instream barriers to rivers. Of these, 45,000 are in Poland. Breaking river connectivity also harms economic activity and the flow of water to the sea. There are also barriers disturbing river connectivity with the floodplains. Such alterations cause structural changes to riverbeds and valley systems, affecting citizens in river basins.

Pollution is the second major threat to Polish waterways. Rivers contain above-normal amounts of toxins and heavy metals from fossil fuel emissions, transport, and industrial discharges. Poland remains a “coal island”, relying on fossil fuel for transport, energy, and heating, despite the Europe-wide transition towards renewables. Besides being coal-intensive, Poland was also the perpetrator of the Odra ecological disaster. But it is also the first country in Europe to have a systematic analysis of what needs to be done to restore and safeguard its rivers. The question is whether it will implement it.

In 2020, the Polish state water company developed a national programme for surface water restoration. The document states that 91 per cent of Polish rivers require restoration measures (in many cases consisting simply in changing watercourse maintenance practices, but in other cases requiring technical restoration measures).

The European Centre for River Restoration defines river restoration as “the process aiming at restoring the natural state and functioning of the river system in support of biodiversity, recreation, flood management and landscape development”. As the EU Water Framework Directive mandates that European freshwaters should be in good environmental condition by 2027, large-scale river restoration in Poland would have to start immediately. But this urgency has so far not been visible in the actions of water authorities.

While the restoration programme provides a strong basis for action, the government remains the key decision-maker. Analysis by the former head of the programme Ilona Biedroń found that the government’s draft river basin management plans are highly insufficient. Restoration efforts most often mean only the construction of fish ladders. In total, only around 30 per cent of rivers would see their restoration needs met, while 27 per cent are set to be affected by new developments transforming their hydromorphology. This is not the direction we and our rivers would like to flow.

Poland’s strategic documents talk of “repairing” rivers, but at the same time outline plans for further exploitation. The tacit assumption of government plans is that environmental measures will only be implemented in the future planning period, i.e. after 2027, which would mean deliberately failing to meet European objectives.

The Odra disaster, one year on

In August 2022, a massive fish kill was recorded on the Odra. Several millions of fish were found dead (360 tonnes were collected) and 500 kilometres of the river spanning Poland, Germany, and Czechia were affected. The fish kill was caused by toxic algae, which multiplied due to the high salinity of mining wastewater discharged into the river. The disaster also hit businesses related to the Odra, such as tourism and fishing. This buildup of human pressure on the river did not happen overnight, data says. But under the additional environmental stress of drought in 2022, it led to disaster.

As the main cause of the high salinity of Poland’s rivers, coal mining is a key challenge for water management. The citizens of the Odra basin, as well as social activists and organisations are well aware of the problem. In the aftermath of the disaster, they reacted much faster than state services, which initially denied the facts.

Intensive research is now underway on both sides of the Odra to stop the “golden algae” bloom and manage the ecological effects of massive fish kill. The International Commission for the Protection of the Oder River against Pollution, an inter-government body set up by Czechia, Germany, and Poland has been following the steps taken closely. According to its official proceedings, unpublished but released for this article:

“In Poland, a number of actions have been taken at the central and local level. Many inspections of sewage discharges into waters were carried out and water-legal permits issued in this regard were revised. A pilot 24-hour monitoring of the physical and chemical parameters of the Odra water was introduced using automatic measuring probes in 9 representative places on the river. ”

“Intervention monitoring is also carried out at 30 points (twice a week) located on the Oder and its tributaries (including the Gliwice Canal), as well as reservoirs and oxbow lakes connected to the Odra. As part of this monitoring, the following are controlled: salinity, water temperature, dissolved oxygen, conductivity, pH, the amount of nutrients, or even algae. An instruction manual on the occurrence of Prymnesium parvum in the waters of the Odra River has been developed.”

“The Polish government has developed an act on the revitalization of the Odra [the Odra Special Act], which streamlines procedures for key investments on the river, appoints the Water Inspection, and increases the amount of fines for water management offences. An early warning system is also being developed for mines operating close to flowing waters, which will inform in electronic form about low water levels, salinity levels or, in the event of a threat, about the need to suspend discharges of sewage into waters, even in quantities provided for in water-legal permits.”[1]

The Polish government’s Odra Special Act is viewed negatively by independent experts and socio-environmental organisations in Poland. The legislation was proposed with a lack of public consultations and relies on a long list of hard hydro-technical investments, which experts argue will bring further destruction to the Odra. In June and July 2023, again, fish kills at specific points of the river were observed, saline discharges are still a threat, and toxic algae are still present.

Nevertheless, something is slowly changing. The industries responsible for introducing salinity and other pollutants into the waters of the Odra have undertaken to reduce their impacts. KGHM, a Polish multinational metal mining corporation, recently announced a huge investment in a plant for the production of evaporated salt from saline mine water. The goal is to reduce the salt deposited with mine drainage waters by around 50 per cent. Meanwhile, some coal mining companies declared their intention to invest in saltwater storage to decrease discharge in critical hydrological conditions and enable better diluting. Communities on the Odra expect these plans and promises to be fulfilled, which would improve the condition of the river.

A transboundary river running through three countries, the Odra demands coordination between countries and stakeholders to make sure that the river is healthy from source to sea. If the environmental and economic impact of the disaster is the result of poor transboundary cooperation, it is now time to set a different example.

The Baltic, a shared sea

As rivers know no boundaries, integrated planning and economic development compatible with environmental sustainability should be agreed upon among all nine countries that have their shorelines along the Baltic Sea: Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, and Sweden.

An excess of agricultural and industrial pollution currently runs into the Baltic Sea. Throughout the region, wastewater treatment and management is still in need of modernisation. As a result of eutrophication, algae blooms can at times prevent bathing in the sea. But most importantly, there are several dead zones where there is no oxygen for marine wildlife.

Seven major rivers, including five transboundary ones, flow into the Baltic Sea: Daugava, Gota, Nemunas, Neva, Odra, Tornio, and Vistula. Together, they cover 50 per cent of the Baltic Sea catchment area, and nearly 55 million people inhabit these rivers’ catchment areas. The southern ones are the most densely populated and have the most intensive agriculture.

HELCOM, the Baltic Marine Environmental Commission, found that 40 per cent of the total nitrogen and phosphorus load in the Baltic Sea is deposited by these seven rivers; among them, the Vistula is the most polluting. The load of nutrient deposits is decreasing, but not at the speed needed to restore the good condition of the rivers and the Baltic.

The problems seen in Poland are felt across the Baltic Sea region. There is an urgent need for the restoration of water ecosystems, the immediate cessation of land drainage in the catchment areas, and wetland restoration. In addition, more land must be made available for the protection of the water bodies, including buffer zones along the river banks to prevent the flow of polluting nutrients. The modernisation and reconstruction of wastewater treatment systems can also play an important role in reducing nitrogen inputs.

Protecting water, restoring nature

The EU Water Framework Directive outlined how to achieve environmental objectives for each river basin. Over 20 years later, it is sufficiently robust in terms of the measures it calls for. The stumbling block has consistently been implementation.

The deadline for EU countries to meet the directive’s legislative objectives was 2015, with the possibility of extension in exceptional circumstances, but no later than 2027. As of today, it appears that not only will the targets not be met, but many necessary measures will likely not be implemented by 2027. This shows that the failure depends on the lack of action by member states, not on the time that restoration naturally requires.

Across the EU, governments are responsible for preparing river basin management plans. Updated every six years, these crucial documents must also undergo public consultation, allowing citizens and civil society groups to help shape the future of their rivers. The current plans (2022-2027) are the last ones before the EU directive’s official deadline.

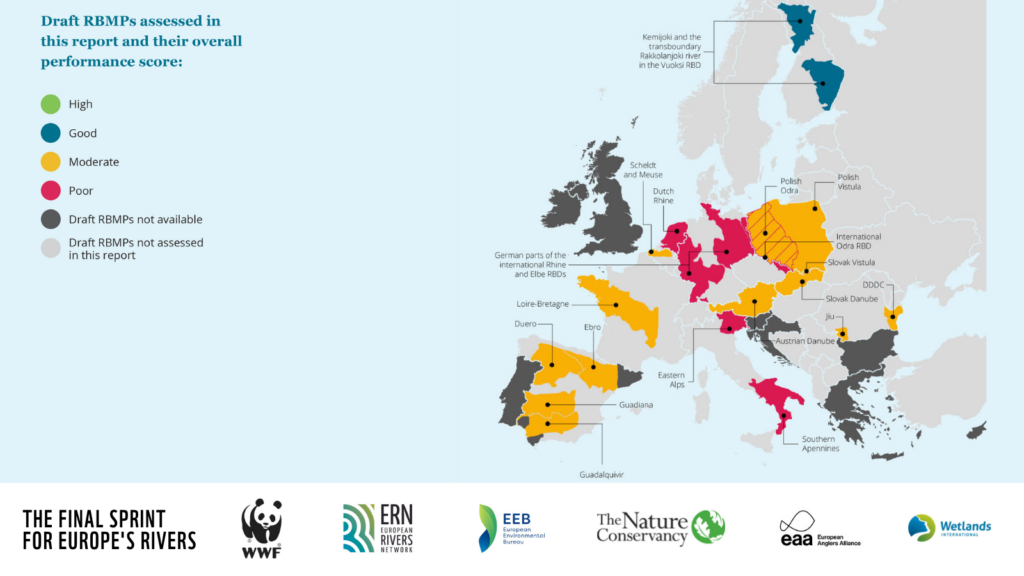

The Final Sprint for Europe’s Rivers analysis, released in 2021, looks at how 21 draft projects in 11 EU member states are dealing with the main pressures on water. Its overall findings show that EU countries are failing to integrate water protection and environmental objectives with energy, agriculture, and infrastructure policies. That is, major economic sectors outsource their environmental and resource costs to river and water systems. Two decades after the adoption of landmark EU water legislation, member states continue to channel enormous amounts of public funds into environmentally harmful activities, which hinder the achievement of a good ecological, chemical, and quantitative status for our waters.

The analysis concludes that most water bodies “will not reach good status by 2027”. For citizens, this means prolonged exposure to the health impacts of a polluted environment.

They are our rivers too

On 5 June 2021, we entered the United Nations Decade of Restoration. The initiative is a global response to the ecological emergency and an expression of governments’ commitment to “build back better” after the pandemic. The EU’s proposed Nature Restoration Law fits into that picture too. And the situation of Poland’s rivers is one of many examples showing that an ambitious restoration strategy is long overdue.

Article 68.4 and Article 74 of the Polish constitution guarantee ecological safety and the prevention of environmental degradation. These provisions are too often forgotten. Policy and government exist to serve the people, not privileged sectors, and what the people need are healthy rivers. All stakeholders should be represented at water roundtables. Yet, at least in Poland, many important decisions about the future of waterways are made between government and economic actors, with no involvement of water authorities.

Society has also become more active in shaping the future of rivers. Coalitions for river protection are increasingly important, from national groups such as the Save the Rivers Coalition in Poland and Aktionsbündnis Lebendige Oder in Germany, to international ones such as the Coalition Clean Baltic and Living Rivers Europe.

Public awareness about the need for healthy rivers is growing, also thanks to initiatives that popularise the life and needs of rivers with accessible language, such as the podcast Zdrowa Rzeka (Healthy River) and the River University, an annual gathering of river stakeholders.

Despite the advances in scientific understanding, an outdated approach to water management is still pursued, favouring technical investments that can do more harm than good over restoration and nature-based solutions. Policies should connect regulatory authorities and practitioners to enable a shared vision for Europe’s waters. Coordinating sectoral policies across areas such as agriculture, environment, economy, and energy is key. The challenges of water management in Poland, in the Baltic Sea region, and across Europe need to be faced bravely and budgeted properly. If the old approach was dominated by lobbying, today we need to think about environmental assets and the citizens’ future.

We now know much about our rivers and how to take care of them. We shouldn’t be scared to swim in them.

¨[1] Translation from Polish of the minutes of the 47th meeting of the International Commission for the Protection of the Oder River against Pollution, G1 Working Group, on May 15-16, 2023.

Thanks to many generous donors BRAVE NEW EUROPE will be able to continue its work for the rest of 2023 in a reduced form. What we need is a long term solution. So please consider making a monthly recurring donation. It need not be a vast amount as it accumulates in the course of the year. To donate please go HERE

Be the first to comment