In order to be effective in stopping the climate crisis unions will have to build alliances with a wide range of progressive social forces around shared commitments.

John Treat is a researcher with Trade Unions for Energy Democracy, http://unionsforenergydemocracy.org/

Cross-posted from Trade Unions for Energy Democracy

For more than a decade, trade union responses to the unfolding climate and ecological crisis have mainly focused on the idea of “just transition.” This idea has brought much-needed attention to the serious disruptions facing many workers, and the need to minimise those disruptions where possible, or provide alternatives where necessary. Unions have generally affirmed the findings of climate science and recognized the urgent need for dramatic transformation of our societies, but this affirmation has mostly found expression in echoing broader social calls for “more ambition” from governments.

At the international level, and especially in Europe, union discourse and engagement around the need for a “just transition” has been shaped profoundly by the fate of social democracy, and the related ideas of “social partnership” and “social dialogue.” But despite their origins in what could be seen as a true “social contract” between roughly equal partners, the erosion of political power for unions in recent decades has largely hollowed out these terms, leaving unions and workers left increasingly dependent on appeals to governments and private companies to “do the right thing” for workers and the planet.

This state of affairs calls for critical reflection. It is vital that unions ask whether existing approaches to the crisis are not only sufficiently ambitious, but whether they are even aimed correctly at the target.

Rising Energy Use and Emissions, and “The Pandemic Pause”

The outbreak of the global pandemic set in motion a chain of events that is expected to result in a record fall in global energy use and emissions in 2020. Many may have been tempted to hope that this fall could represent a turning point in the struggle for climate protection, but this could hardly be further from the truth. In the words of Dr. Fatih Birol, Executive Director of the International Energy Agency (IEA): “Despite a record drop in global emissions this year, the world is far from doing enough to put them into decisive decline.”[1] Low economic growth, he added, “is not a low-emissions strategy — it is a strategy that would only serve to further impoverish the world’s most vulnerable populations. Only faster structural changes to the way we produce and consume energy can break the emissions trend for good.” Far from helping catalyse systemic change towards a low-carbon future, the pandemic crisis has thrown the lives of working people into chaos, decimated unions, and undermined the capacity of public authorities to respond either to the immediate crisis, or to the larger crisis still lurking behind it.

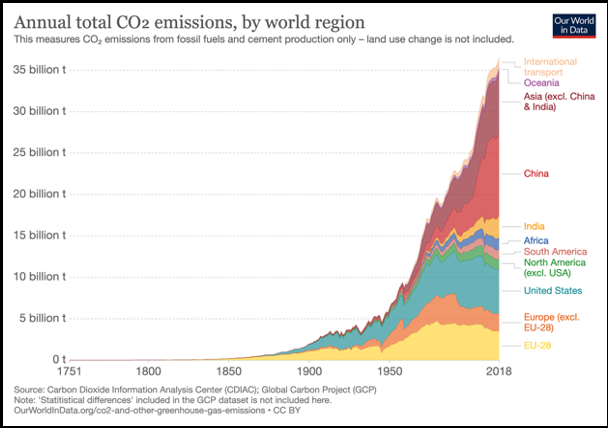

In the years before the pandemic, it had become increasingly clear that, globally, the world is not experiencing a transition to sustainable energy systems, but rather a reconfiguration of energy sourcing, against the backdrop of an overall expansion of energy use. Despite some modest reductions in the use of some fuels in some places and some sectors, overall demand for energy has continued to rise even faster than the deployment of new, “clean” energy sources, so that nearly all sources of energy are growing together, and few countries are on track to reach even the very inadequate, minimal targets they agreed under the 2015 Paris Agreement.[2]

As of 2019, according to international consulting firm PwC, simply limiting overall warming to 2°C would require reductions in global “carbon intensity” — the amount of carbon released during productive activity for each unit of economic value produced — of roughly 7.5% per year, every year, until 2100; achieving the somewhat less dangerous target of 1.5°C would mean annual reductions of 11.3%.[3] In the words of the report’s authors, “There’s a huge gap between the rhetoric of the ‘climate emergency’ and the reality of an inadequate global response.”[4]

For unions, it should be clear that the transition to a sustainable, low-carbon economy is not happening — and furthermore will not happen without a radical shift in politics. Unions should also know very well that there is almost no chance that such a shift will take place at all without a decisive contribution from the international labour movement.

“Just Transition”: Two Visions

The idea of a “just transition” for workers facing displacement has its roots in work by the leadership of the U.S. Oil Chemical and Atomic Workers Union (OCAW; now part of the United Steelworkers) to negotiate support for workers facing closure of a New Jersey chemical facility in the mid-1980s. Under the leadership of OCAW President Tony Mazzocchi, the union sought not only income protection for the plant’s 650 workers, but government-funded retraining for those to be displaced. But Mazzocchi understood “just transition” as not merely the pursuit of “safety net” provisions, but as a means of raising deeper questions about societal priorities and principles, in order to help workers imagine a different future.[5]

In our 2018 Working Paper, “Trade Unions and Just Transition: The Search for a Transformative Politics,” we distinguished between two distinct conceptions of “just transition” that have shaped trade union debates: a narrow conception focused essentially on workers alone, and a broader conception focused on the need for radical social and ecological transformation.[6] Union debates have not always recognized these very different meanings of just transition. While many unions understand that they must address the concerns of workers in the here-and-now, fewer seem to have internalized the need to exert maximum effort towards ensuring a radical socio-ecological transformation, rather than simply appealing for a fair management of the fallout of industrial reconfiguration, encouraging employers to “green the workplace,” or pressing for decarbonization targets in collective bargaining processes.

Just Transition, Social Dialogue, and the Crisis of “Social Europe”

This is not the place to recount the history of social partnership and social dialogue in Europe. But the outcomes of that history are crucial to recognize and understand.

The institutionalization of “social dialogue” in Europe, beginning with the Treaty of Rome and continuing through further commitments in subsequent years, effectively codified a rejection of “class struggle” politics in favour of “permanent peace.” That rejection of continuing conflict came, however, from a position of exceptional and growing trade union strength at the time — the product of decades of militant, class-based activism (including industrial action) in the early and middle decades of the twentieth century, bolstered by the existence of the Soviet Union and ongoing anti-colonial and national liberation struggles in the global South.

With the post-war recovery, social democratic and socialist parties broke, one by one, with their more radical pasts and embraced the compromise — a compromise that delivered real results: union recognition; real social protections (the “welfare state”); a relatively fair distribution of the (growing) economic surplus. Whatever gains were to be had through that specific compromise were made possible by the actually existing power of the international labour movement (and the configuration of geopolitical realities) at the time. In the words of Norwegian trade union activist Asbjørn Wahl, “It was the result of a very specific historic development, in which the trade union and labour movement was able to threaten the interests of capital through mobilisation and struggle.” In other words, it was not a result of appeals to employers, but of “having taught them a lesson through industrial action.”

The turn to neoliberalism beginning in the 1970s brought a steady reversal of the post-war gains. Collective bargaining would be gradually but surely undermined, leading one researcher to observe in 2013, “Systems of collective bargaining that were once robust have been systematically eroded and destroyed. The collective agreement itself — as an instrument for collectively regulating wages and other employment conditions — is manifestly now at risk.” A 2017 assessment by the European Trade Union Institute (ETUI) similarly noted, “the trend has clearly been towards lower collective bargaining coverage, which directly goes against the declared objective of the EU to increase the role of collective bargaining.”

This linking of “just transition” with the idea of “social dialogue” began more than a decade ago, when the ITUC joined UNEP and the ILO in promoting a jobs-focused vision of “green growth.” What had begun life as a set of radical demands aimed at winning protections for workers while raising fundamental questions about political economy, began to be seen as a means to “bring economic life into a democratic and sustainable framework… grounded in meaningful social dialogue and driven by broadly shared economic and social priorities.” Although the full implications of this shift linking “just transition” and “green growth” may not have been appreciated at the time, in retrospect it may have marked the beginning of a fateful turn towards the instrumentalization of “just transition” — turning it from a project to raise awareness about the need for radical social transformation, into a means for breathing new life into the faltering project of social democracy.

Another factor undermining prospects for social partnership and social dialogue to deliver a real “just transition” has been the collapse of support for the major social democratic parties. The embrace of “Third Way” thinking marked an important ideological shift among many such parties, but the full impact may only have become apparent with the financial crisis and economic collapse of 2007-09, when social democrats joined parties of the centre and right in administering deep austerity. The results were catastrophic for millions of people across Europe, as well as for the parties carrying them out, which saw electoral support collapse in France, Germany, Greece and elsewhere.

Confronting the Crisis and Forging Another Path

The implications may be unpalatable but must be confronted. It is clear that “climate action” is not taking place at anything like the speed and scale required to avoid catastrophic climate impacts. Workers around the world are being displaced by reconfigurations of energy and other sectors, but the changes wreaking havoc on their lives are not even sufficient to protect the climate for their children. The Europe that produced meaningful “social partnership” and “social dialogue” no longer exists, and the political space in which such an approach could deliver a “just transition” has been severely constrained through a series of EU treaties and directives.

A growing number of unions are now working together towards an approach to “just transition” that embraces and works to strengthen the social power of the international labour movement, and is willing to deploy it. This “social power” approach is guided by the belief that a “just transition” cannot be accomplished without a deep restructuring of the global political economy. It is guided by the belief that current power relations must be challenged and changed.

In relation to energy, the “social power” approach means organizing to reclaim and extend full public ownership and democratic control of energy. A commitment to “social dialogue” that takes contestation over ownership off the table has already lost the fight for climate protection, relinquishing responsibility for existential decisions to big business, and serving the neoliberal agenda that aims to “liberalise and privatise to decarbonize.” The promise of “green jobs” has proven again and again to be frequently hollow — often monstrously so, as in the case of workers at Scotland’s BiFab, abandoned for the manufacture of wind turbine jackets to be deployed off the Scottish coast, which will instead be built in Indonesia.

Meeting this challenge requires not only a more candid embrace of the reality and sharper political conclusions, but also a level of detailed, programmatic work that will require time and commitment. This task must be international in scope, must involve planning and cooperation at all levels, and must proceed with unprecedented intensity. Most crucially, if unions are to develop effective responses to the climate and ecological crisis, they must abandon any pretence that the transition to a sustainable future is in any way assured by having a “seat at the table.” Dramatic change at this point is inevitable, but a transition to a sustainable future is not — let alone a “just” one.

The international trade union movement is uniquely placed to serve and lead in the pursuit of a truly just transition to a truly sustainable future. In fact, it is difficult to imagine how the transformations required could even begin to take place without decisive leadership from the international trade union movement. In order to be effective, such leadership will also have to build alliances with a wide range of progressive social forces around shared commitments. If ever the trade union movement had a “historic mission,” it is this. And the time is short.

Be the first to comment