Sometimes historical events occur and no one really notices. The decision of the German social democrats to once again enter a grand coalition heralds the end of a political party with a history of over 150 years. But no one really cares, anyway. With its pact with neo-liberalism it lost its soul.

Mathew D. Rose is an Investigative Journalist specialised in Organised Political Crime and an editor of BRAVE NEW EUROPE.

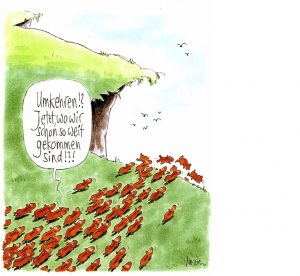

“Turn around? But look how far we’ve come.”

Caricature by

As I participated in my first political demonstration in Germany in 1979 – against nuclear energy – the chant I learned was “Wer hat uns verraten? Die Sozialdemokraten” (Who betrayed us? The Social Democrats). This harks back to 1914 as the then left-wing Social Democratic Party (SPD) voted to support Germany’s entry into the first world war. Betraying its voters is what the SPD has been doing ever since – except maybe during the chancellorship of Willy Brandt (1969 to 1974).

While the SPD portrays itself as a centre-left party, at least when elections occur, it is rabidly neo-liberal. The SPD has been in decline since Gerhard Schröder was elected chancellor in 1998 and, together with the Greens, smashed the social market economy. Like Tony Blair and Bill Clinton he realised that neo-liberalism was the ideology to bet on. He was – and will probably remain – the last Social Democratic chancellor of Germany. Schröder and many of his fellow cabinet and junior ministers from the SPD and the Greens went on to become well-paid lobbyists for international corporations. Schröder himself works for Nord Stream (a German Russian gas pipeline company) and Rosneft (a state-owned Russian oil company).

The party has lost its political credibility, as Germans increasingly view it simply as a collection of self-seeking, corrupt politicians working against their interests. In the recent national election it had its worst result in post-war Germany, just scraping together 20 percent of the vote – something it will probably never achieve again.

Although the party is still strong in some parliaments of Germany’s 16 federal states, it is only the third or fourth largest parliamentary group in a quarter of those state parliaments. This trend will increase in the coming years if surveys are to be believed. On the national level the SPD, according to the polls, is in a duel with the ultra-right party, Alternative for Germany (AfD), for second place. The AfD, like populist parties everywhere, claims that Germany’s political class are thoroughly corrupt, and interested only in filling their own pockets, not in the welfare of the nation. That has been confirmed by the composition of the newest version of the grand coalition as put together by Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats and the SPD.

How did Germany arrive at yet another grand coalition? The logic behind grand coalitions in Germany used to be that in times of crisis it would enable the government to act decisively. It consciously sacrificed the chance of a strong opposition, something rather necessary for the exercise of true democracy. Grand coalitions are the sort of thing that is supposed to transpire maybe once in a generation. This will be the third in the four parliamentary terms since 2005.

To make matters worse, the SPD became entangled in its desire to appear to be a centre-left democratic party (at their party convention I attended a few years ago members were singing the Communist International in the lobby) and the reality that it has sold itself to neo-liberal forces.

The question of forming yet another grand coalition has highlighted this. Following the recent elections the then SPD leader Martin Schulz declared that the SPD’s poor election results were a resounding message from voters that they no longer wanted a grand coalition. Schulz promised that the SPD would respect the will of the German people. Actually this was an empty gesture, since Ms Merkel had plans for a coalition with other parties. Unexpectedly her other coalition plans failed. Leading SPD politicians realised that the gravy train was again on offer and declared, with the support of corporate media, that it was their patriotic duty to provide Germany with a stable government in the form of a new grand coalition. As most Germans reacted with incredulity, the SPD tacked on a further goal: to create a stronger Europe. Nothing however changed in favour of SPD policy. Germans had assumed the SPD would drive a very hard bargain, since Ms Merkel’s political survival depended on a deal. But the coalition negotiations actually ended up with a continuation of the old neo-liberal programme. The reason became clear shortly afterwards.

The last session of negotiations for the grand coalition was purportedly the longest and hardest. The media reported that Schulz had fought like a lion to clinch the deal to save Germany. Later it came out that the day and the night had been spent arguing about who got which ministerial post. The SPD had traded policy for ministries. Schulz who, besides promising not to resurrect the grand coalition, had declared he would never serve as a minister under Ms Merkel, had bagged the foreign ministry for himself. In the eyes of the public, this went beyond betrayal. It was blatant greed. The SPD finally saw this as an opportunity to dispose of the increasingly unpopular Schulz.

Most Germans do not want another grand coalition. At the SPD’s special party congress in January, attended mainly by party functionaries, four more years of well-paid jobs were on offer, as well as bribes and donations from corporations. Still, the decision was close. Senior SPD politicians – who wanted one more helping from the corporate trough – were pitched against the junior members, who feared they would never make it to the trough. The latter knew that a grand coalition meant the party would be doomed to extinction. Their idea was to renew the SPD in opposition.

This still does not explain why 66 percent of SPD party members ended up voting for this fatal grand coalition. To understand this one has to look at the structures, demographic and cultural, of the SPD. The average age of SPD members is over 60. That means most of them were socialised in the post-Nazi era, which was very authoritarian. The SPD served them well, improving their living conditions, increasing social mobility, supporting unions. However the SPD is a party created in the time of the Kaiser: authoritarianism was embedded in its relationship with its members, something from which it has never emancipated itself. The trade-off was clear: we improve your life, you vote as you are told. As one SPD functionary put it: “You can count on our members”.

Schröder terminated this arrangement. The SPD knew however that while younger Germans are not terribly politically active, elder citizens vote. While younger Germans today are confronted with a deteriorating economic situation ushered in by the SPD, the party has been very generous with pension increases for those citizens who are already retired – and vote for them. For most Germans however the SPD has become irrelevant. Inequality is high (and increasing), 1.5 million Germans use food banks.

Another relic of the old Kaiser government is corruption. This tradition was reborn after the second world war. A German journalist colleague related an interesting story: after the war the West-German politicians drummed together the owners of the German press, blaming them for being a major element in discrediting the “democratic” parties as corrupt during the Weimar Republic, enabling the Nazis to come to power. What the politicians offered in return for freedom of the press was not to eradicate corruption, but that the media should not report on it. This functioned for quite a while. The first major post-war corruption scandal in West Germany came to light in the 1980s, and of course had no real consequences. Germany was one of the last nations to permit its companies to deduct bribery payments from their taxes (no questions were asked concerning the recipient). Interestingly, since the ultra-right AfD has become a political force in Germany and has raised the issue of corruption in government, the amount of reporting concerning political corruption in corporate media has radically decreased. It is mainly thanks to a couple of NGOs and independent websites that the topic has not disappeared altogether.

With its volte face on the grand coalition the SPD has signed its own death warrant. But it was caught between a rock and a hard place: if it opted for a grand coalition it would be considered hopelessly corrupt; if it opted against joining Ms Merkel the corporate press would scream that the SPD had let down the nation. The die was cast months ago, when the SPD first raised the spectre of a new grand coalition. The rest was window dressing.

It is high time for Germany to rid itself of a party that belongs to another political era. With maybe the exception of some SPD functionaries and employees, no one will really miss the party and its ceaseless betrayals.

Be the first to comment