‘Green growth’ withers in the heat of evidence. Humanity’s demands are creating a ‘global land squeeze’. Another year of murder for environmental defenders.

Peter Sainsbury is a retired public health worker with a long interest in social policy, particularly social justice, and now focusing on climate change and environmental sustainability

Cross-posted from Pearls and Irritations

Green growth: saviour or snake oil?

Economic growth, expressed as an ever-expanding GDP, often justified with the claim that a larger pie makes for a fairer redistribution of its delights, is frequently presented as an unchallengeable necessity and a desirable social goal. Those pro-growthers who are aware of and want to tackle climate change (and other environmental problems created by industrialisation) insist that endless economic growth can be ‘green’. That is, they assert that the direct positive association over the last two centuries between GDP and CO2 emissions can be broken; that GDP can keep rising indefinitely while CO2 emissions fall to zero. This is often expressed as ‘absolute decoupling’ of emissions from GDP.

If we assume for a second that absolute decoupling is possible, and bearing in mind the tremendous urgency of reaching net zero CO2 emissions, the next question is ‘can absolute decoupling be done quickly enough to meet the requirements of the Paris Agreement, prevent warming of 1.5oC and avoid at least some of the looming environmental and human catastrophes?’

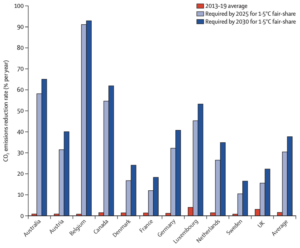

Between 2013 and 2019, of 36 rich countries for which there was appropriate data, 11 (including Australia) had achieved absolute decoupling of their GDP from their consumption-based CO2 emissions. However, not one of those 11 got within cooee of doing it fast enough for them to meet their fair share of global emissions reductions for the world to have even a 50% chance of limiting global warming to 1.5oC. Each country’s ‘fair share of emissions reductions’ was calculated by weighting the global carbon budget to stay under 1.5oC by its population size. The historical carbon debts of the 11 rich, industrialised countries were ignored, being regarded as a separate issue that is best handled through other mechanisms.

The 11 decoupled countries would each take not 30 years (from 2020 to 2050, the target date for net zero CO2 emissions) to reach net zero but somewhere between 70 and 370 years. On average it would take them 220 years and they would burn 27 times their carbon budgets. The eleven’s average CO2 emissions reduction rate for 2013-2019 was 1.6% per year. This would need to increase to about 35% per year for them to meet their net zero targets by 2050.

Australia (which with Belgium, Austria, Canada and Germany is one of the lowest-performing of the 11) would now need to achieve a CO2 emissions reduction rate of around 60% per year to achieve our fair share reduction, more than 30 times our recent rate (see graph below). In fact, we’d need to hit net zero emissions about 2029 – no, that’s not a typo; yes, it’s six years away.

The authors conclude: ‘green growth approaches are inadequate for high-income countries to deliver on their Paris obligations. Further economic growth in high-income countries is at odds with the climate and equity commitments of the Paris Agreement. Narratives that celebrate decoupling achievements in high-income countries as green growth are thus misleading and represent a form of greenwashing.

If high-income countries are to reduce emissions in line with the Paris Agreement, they will need to abandon the pursuit of aggregate economic growth and instead adopt equitable and sufficiency-oriented post-growth policies’.

And remember, first, that these 11 countries are the best performers among 36 rich nations, the ones that have actually achieved some decoupling of GDP and CO2 emissions; second, that collectively the 11 are responsible for only 7% of current annual global CO2 emissions; and third, that it was a pretty low bar of ultimate success, just a one in two chance of staying below 1.5oC.

Saviour or snake oil? You decide!

Penny Wong ducks and weaves in New York

Christiane Amanpour, CNN: ‘You have said that climate is the number one national security issue in the Pacific. And yet the government is expanding coal mining this year. Can you honestly say that your record on climate is in the right direction?’

Foreign Minister Wong: best to watch Penny’s verbal terpsichorean skills for yourself.

Penny Wong was in New York for the annual meeting of the United Nations in September. But why, you ask, was she being asked about Australia’s climate hypocrisy? Here’s the reason.

At least one man remains hopeful

UN Secretary-General António Guterres convened an international Climate Ambition Summit on September 20th to take advantage of the presence in New York of many government leaders. At the end of the Summit, Guterres said:

This started as the Climate Ambition Summit and I believe it ends as the Climate Hope Summit. The 1.5 degrees limit is possible to be achieved.

We are in many aspects even moving backwards. I was in the G-20. I was quite disappointed by what the G-20 concluded about climate, because the geopolitical divides are still not allowing for what must be an historic compromise between developed economies and emerging economies that are the biggest emitters.

It’s true that we still see many fossil fuel companies, asset owners, other companies that seem to be betting and investing in the same logic of those that, in the beginning of the [20th] century were betting and investing in horse drawn carriages, thinking that will guarantee their maximum profits.

But a meaningful number of countries, regions and cities are already fully aligning their policies with the 1.5 degrees goal. There are companies, and there are asset owners and other financial institutions that are already aligning their strategies or their portfolios with a 1.5 degrees strategy.

So, to all the first-doers that are here today, and I think now it’s a matter of doing, I’d say: ‘Scale up. Bring together all those that you can bring together with you.’

But the world’s political leaders didn’t attract all the attention in NYC. The community also had their say, many regarding Guterres’s initiative as the Unambitious Climate Summit and expressing their frustration in the streets and in front of the Federal Reserve Bank. In fairness, Guterres himself is trying as hard as he can to drag the world’s nations to effective climate action.

‘Buy land, they’re not making it anymore’

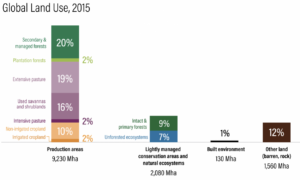

Currently, as the World Resources Institute (WRI) figure below details, over 70% of the world’s (ice-free) land surface area has been significantly impacted by humans. Although concrete, steel and glass are what many of us see most in our daily lives, the built environment occupies only about 1% of land surface area, approximately 70% is devoted to growing things that we eat, wear or inhabit.

Worldwide, agricultural use has resulted in clearing or converting 70% of grassland, 45% of temperate deciduous forest and 27% of tropical forest, and draining about half of the wetlands. If we continue current trends, to feed the increasing size and affluence of the global population we will need to expand agricultural land by an area about the size of Australia between 2010 and 2050. Fulfilling the world’s growing demand for wood during the same period will require an even larger area. Then there’s the need for more land for the fibres we wear, sit on, sleep in, etc. and the materials we use for human habitation and infrastructure. All the while, we must reduce greenhouse gas emissions, not destroy carbon sinks, halt the loss of biodiversity and respect Indigenous rights.

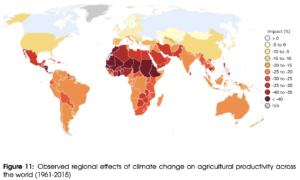

On top of all that, we must also manage the declining productivity of the agricultural sector as global warming increases. To date, agricultural productivity has decreased by about 20% globally as a result of climate change. The reduction has been greatest in the countries to the south of the USA, Europe and China, and has been particularly marked in Central America, North Africa, and the Middle East (all considered to be part of the Global South even though they are all north of the equator).

The WRI recommends four ‘Pillars’ for successful management of the ‘global land squeeze’ – i.e., society’s competing demands on the world’s finite land resources:

- Sustainably produce more food, feed, fibre and wood from existing lands. This will necessitate increasing annual crop yields by 20% and meat and dairy yields by 60% compared with 1960-2010;

- Protect remaining natural and semi-natural ecosystems from conversion and degradation. All conversion and degradation of forests, grasslands and forests should stop by 2030 at the latest;

- Reduce the demand for goods that have a large land footprint. For instance, reduce food loss and waste, shift diets to more plants and less meat, particularly in rich countries, reduce the demand for bioenergy, avoid creating additional demand for wood products, and promote high-density, liveable cities;

- Restore degraded ecosystems and marginal agricultural land to nature. For instance, reforest an area the size of Australia and restore peatland in an area equivalent to half of NSW by 2050. I’m no expert but this one seems to me to be the most challenging Pillar to implement.

To add to the difficulty, but also increase the chances of success, all four Pillars need to be pursued simultaneously and in a coordinated way. Equally importantly, implementation must improve the lives of people, especially the most vulnerable, e.g., reduce poverty, make food affordable, reduce rural unemployment, empower women, and respect Indigenous people’s territories.

The second clause of Mark Twain’s quotation that heads this piece is a pertinent observation but one might argue that the recommendation in the first clause is a large part of the problem. Some believe that land (and the world’s other natural resources) should belong to all humanity, be part of the common wealth, not be privately owned for the accumulation of personal wealth. To quote Karl Polanyi in1944: ‘What we call land is an element of nature. To isolate it and form a market for it was perhaps the weirdest of all the undertakings of our ancestors’.

Hundreds more environmentalists murdered

I think I cover this issue every year, for obvious reasons. In 2022 at least 177 environmental activists were killed for defending their land rights and protecting nature. More than a third were Indigenous people. Columbia (60 killings), Brazil (34), Mexico (31), Honduras (14) and the Philippines (11) are particularly dangerous places.

These numbers represent only those victims than can be clearly identified. The actual number for Brazil may be close to 200. Thanks goodness that Global Witness, an NGO, documents the murders when they can. They can’t stop the intimidation, violence and murder but they do ensure that it doesn’t go completely unnoticed.

Sarapo Kaapoor was murdered for defending the rainforest land of the Ka’apor people in Brazil from destruction by cattle ranchers, soy planters, loggers and mining companies, with drug cartels also using the activities to launder drug money.

Be the first to comment