The EU, notorious den of money laundering, taking years to finally have a functioning authority and most concerned about where the offices will be.

Sebastian Diessner is an Assistant Professor at Leiden University

Cross-posted from LSE EUROPP

Until recently, the question of who is in charge of cracking down on money laundering in Europe should arguably have been answered with: ‘the US’. After all, it has been the US Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) that has acted as the sheriff in terms of discovering and penalising major scandals among European banks failing to live up to their anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing requirements in recent years.

These have included investigations into the Estonian branch of Danske Bank for laundering no less than €200 billion over the course of a decade and several probes into Deutsche Bank, including for its implication in a laundromat scheme that enabled the laundering of another $20-80 billion (many details of which only became known through the FinCEN Files leak), in both cases out of Russia.

But this might be about to change. The European Union has belatedly woken up to the challenge and has proposed legislation which effectively strips the European Banking Authority (EBA) of its few anti-money laundering powers, to the benefit of a proper EU-wide authority – a step which had long been called for by MEPs and outside observers. With the zeal of a convert, the new Anti-Money Laundering Authority (AMLA) is now supposed to be established by 1 January 2023 already, although it is only expected to be operational by the beginning of 2024, to be fully staffed by 2025, and to directly supervise financial institutions as of 2026. As a result, a number of key questions remain.

Why now?

Debates about centralising capacities to fight money laundering at the European level are at least as old and contentious as those around Europe’s economic and monetary union. When the euro was set to be introduced in the late-1990s, Germany in particular became one of the holdouts who staunchly opposed progress in the area of anti-money laundering, on the spurious grounds that it would force the German state to interfere with its independent judiciary. In reality, according to participants at the time, it seemed that policy-makers rather sought to protect an industry of legal and accounting professionals who benefitted greatly from lucrative financial activities that enabled money laundering (professionals which the Council of Europe’s Moneyval committee nowadays refers to as ‘gatekeepers’ and the US House of Representatives as ‘enablers’).

Why and how (and perhaps even whether) such long-standing opposition has finally been overcome is a pertinent question for future research. For now, we may take ‘comfort’ with the functionalist explanation that the sheer scale of the problem, and the failures to resolve it, have become plain for all to see: according to one recent report, 90% of the biggest European banks have been found culpable of money laundering activities in the past decade.

One root cause of the current malaise has been the patchy transposition and enforcement of previous anti-money laundering directives on behalf of EU member states and the leeway they were given by the European Commission, which has resulted in a fragmented regulatory landscape marked by a critical lack of coordination. The new authority will be expected to rectify some of these shortcomings.

What will it do?

The current legislative proposals suggest at least three main functions for the new authority: the harmonisation of supervisory practices in both the financial and non-financial sectors; the coordination of financial intelligence units (FIUs) and other institutions across member states; and, most importantly perhaps, the direct supervision of high-risk and cross-border financial entities.

However, the list of possible tasks and responsibilities appears to be growing by the year, now also encompassing the supervision of crypto assets and perhaps even the enforcement of economic sanctions related to the war in Ukraine. All of this raises immediate follow-up questions, including how AMLA’s relationships with existing national and international authorities will be structured, which risks it will prioritize, and, above all, how many and which entities it will directly supervise. Moreover, the exact set of functions that AMLA is ultimately expected to fulfil will (or at least should) influence the upcoming battles over finding an adequate home for the authority, which are about to kick off in earnest.

Where will it be based?

The most immediate question, perhaps, relates to AMLA’s location. Although the authority is slated to become established and open its doors over the course of the coming year, where exactly those doors will be still remains anyone’s guess. What does it take to host an EU regulatory agency?

If the epic battle over who would become the new host of EBA after Brexit (officially fought out between Brussels, Dublin, Frankfurt, Luxembourg, Paris, Prague, Vienna, and Warsaw at the time) is anything to go by, the brochure of the successful Paris bid suggests that it is all about making the location attractive and accessible to prospective staff (the same goes for Amsterdam’s successful bid to host the European Medicines Agency, trumping no fewer than 18 other offers from across the EU). The recently adopted Council position on concluding a headquarters agreement for AMLA is sparse, but it does highlight the need for ‘the best possible conditions to ensure the proper functioning of the Authority, including multilingual, European-oriented schooling and appropriate transport connections’.

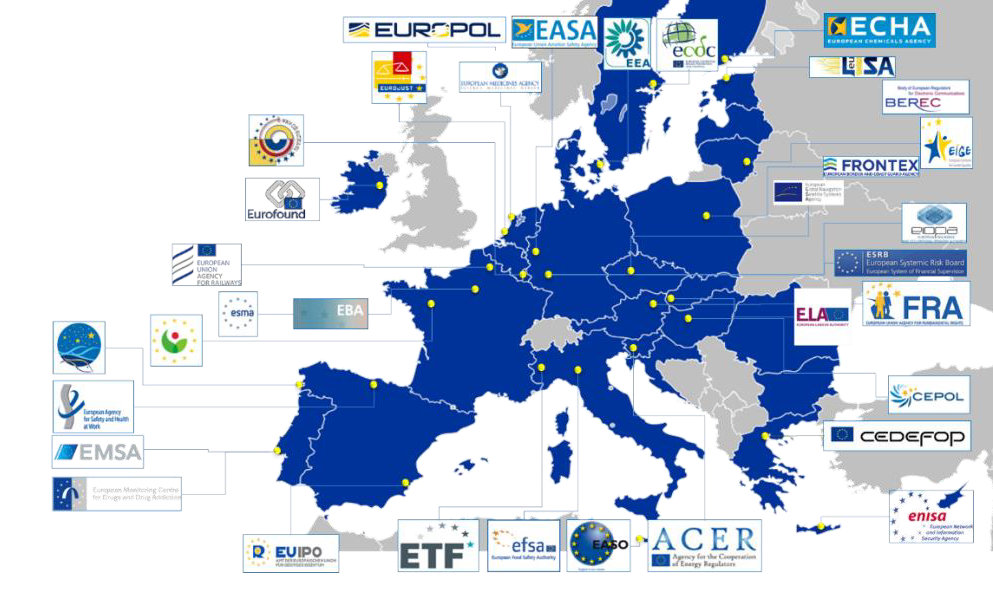

Figure 1: Location of EU agencies

Source: Kaeding (2020), More important than ever – EU agencies in times of crisis, European Institute of Public Administration

At a more fundamental level, however, the allocation of agencies between member states is one of the major horse-trading exercises which characterise EU politics and which may or may not ultimately be decided by the actual qualities of the prospective host countries and cities. Organisational synergies and geographical distribution are among the key variables that will need to be reconciled. Here is a selection of the various potential hosts that have been floated together with some of the arguments that may speak for or against them:

Germany (Frankfurt)

One might deem it a supreme irony – given the aforementioned opposition to supranational anti-money laundering capacities and underwhelming track record in preventing money laundering – but Germany is one of the main contenders for hosting AMLA (and is said to have already made budget preparations to this end, in addition to announcing an own national authority). This is in large part due to the significant overlaps between anti-money laundering and financial supervision, the latter of which is currently under the auspices of the Single Supervisory Mechanism housed at the Frankfurt-based European Central Bank. Among others, a major money laundering scandal at the ECB-supervised Latvian bank ABLV in 2018, which was first flagged by FinCEN, put the central bank on the spot for its lack of information and powers in anti-money laundering.

Netherlands (The Hague)

Despite Amsterdam being the financial (and national) capital of the Netherlands, it is the administrative capital The Hague which hosts two key agencies that are already cooperating successfully with member states in the fight against money laundering, namely Europol and Eurojust, thus creating obvious potential for synergies. While the Netherlands’ largest bank ING has had its own major failings in the area of anti-money laundering, those have at least been dealt with at home by Dutch prosecutors, including a landmark probe into ING’s former CEO (and current UBS CEO) Ralph Hamers.

Italy (Rome/Milan/Palermo/Turin)

The names of various Italian cities have circulated in terms of applying to host the new authority. Italy is deemed to have made ‘good progress in establishing the legal, regulatory and operational framework’ for anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing, according the latest follow-up report by the G7-initiated Financial Action Task Force, owing in large part to the leadership of the Banca d’Italia’s Financial Intelligence Unit.

Austria/Estonia/Ireland/Latvia/Lithuania/Poland

Vienna, Tallinn, Dublin, Riga, Vilnius, and Warsaw have all been rumoured in recent months to be throwing their respective hats into the ring as well. Achieving some geographical balance in the overall distribution of agencies will surely feature in the upcoming discussions, as is common for the EU (see figure above for an overview).

In sum, we currently have far more questions than answers indeed. Consequently, more work by policy-makers – and closer observation by researchers and other stakeholders – on the details of the EU’s anti-money laundering agenda over the coming months and years will be needed if one is to make sure that the question of who is in charge of anti-money laundering in Europe can finally be answered with: ‘the EU’.

Support us and become part of a media that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking going.

Be the first to comment