Trying to determine why Stalin initiated the Great Terror resulting in so many deaths.

Branko Milanović is an economist specialised in development and inequality. His new book, The Visions of inequality, was published October 10, 2023.

Cross-posed from Branko Milanović’s blog Global Inequality and More 3.0

As I mentioned on Twitter, I just finished reading the second volume of Aragon’s Histoire de l’URSS (published by Edition 10/18 in 1962). It is purely by accident that last week, when I was in my apartment in Belgrade which is stuffed with hundreds of books bought by my father and myself when I was young, that I stumbled upon Aragon’s three volume opus. I chose the second volume, running from 1923 to the end of the Second World War. The picture on the cover was appropriately that of Stalin.

The book is strangely part of a UNESCO project done in the early 1960s, imagined and directed by a UNESCO official, Carlos de Azavedo. UNESCO commissioned André Maurois, a French writer and biographer, to write a history of the United States, and Aragon, the history of the Soviet Union. Aragon who was a poet, not a historian, but a dedicated Communist party member spent two-and-a-half years collecting and readings reams of documents. Because of Aragon’s Communist links he obtained access to some Soviet archives that were, at that time, closed to other researchers. Despite a very sympathetic treatment that Aragon gives to the Soviet Union, the book was never published there. By the 1990s it probably became obsolete as much new evidence was unearthed.

However, it would be wrong to dismiss the book. It is ideologically very Khrushchevian, and gives us an insight into what the accepted (Khrushchev’s CPSU) version of Soviet history was: dismiss Trotsky because of innumerable political vacillations, downplay the importance of Zinoviev and Kamenev, accept that Bukharin was (in Lenin’s words), the “darling of the Party”, and attack Stalin for the cult of the personality and the Great Terror, but otherwise accept that he accomplished great things. Aragon elides the human costs of collectivization, laying the blame on kulaks’ intransigence on the one hand (and never questioning who the famed “kulaks” were), and abuses of the individual party members and secret police on the other. Things become more alive with the Great Terror of 1936-38 when Stalin is unambiguously portrayed as a tyrant. Foreign policy of the USSR is throughout, but especially after the mid-1930s, presented in an undiluted favorable light, and all the blame on the lack of cooperation between France, Great Britain, and the USSR against Nazi Germany is placed on the former two countries. While an informed reader is sometimes startled by Aragon’s statements (e.g. the unmitigated enthusiasm of the working masses in the Baltic countries and Bessarabia when being annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940), there are nonetheless the facts that Aragon brings up and that are in today’s historiography forgotten or ignored. In that sense Aragon’s book is a useful antidote to today’s versions of history: it pushes the reader to look for the discussion of the events that he or she was not even aware happened.

There is an also an element that Aragon, perhaps because he was a poet, provides that other, more sober, historians do not. It is an almost lyrical juxtaposition between a huge working elan of thousands of young people unleashed by the Revolution and dark murders happening at the same time. This is brought with especial poignancy during the Great Terror. At the same time when top Bolshevik members are dragged by dark NKVD creatures, killed, and their families dispersed across the Soviet Union, ordinary workers achieved remarkable feats of productivity, new factories were built, children sang songs, and many believed they lived in most glorious times ever. Only a poet can see the light and darkness as coexisting so dramatically and daily: a person who gave the most uplifting Stalinist speech in the morning may be arrested in the evening and executed at dawn.

The description of this period brought me back to the greatest puzzle of all with which I grappled with since my teenage years: What was the objective of the Great Terror? Why did Stalin want all these people killed? As Bukharin wrote to him in a note found in Stalin’s drawer after Stalin’s death, “Koba, why do you need my death?” Nobody knows.

I have read at least a dozen of books that, directly or indirectly, try to explain the Great Purge. I am convinced that the purge cannot be explained by looking at it narrowly, that is only at the time when it happened, without knowing or discussing the events from 1917 to 1936, or even going back to before the Revolution. Even then, it remains a puzzle. Stalin wanted to kill everybody who was close to Lenin and was an “Old Bolshevik” so that he himself may be the only correct interpreter of Leninist legacy and no opposition could ever coalesce along a generally recognizable political figure? Yes, it is possible—but how would it explain that about 500,000 people were executed too: half-a-million people were certainly not Lenin’s close collaborators nor likely leaders of the opposition. And how does it explain the decimation (or more) of the entire officer corps of the Red Army? Did the Red Army brass show any tendency to overthrow Stalin? No. Was Trotsky’s influence there, on account of his past, particularly strong. No.

Was it an attempt to shift the blame for the failures of industrialization onto “wreckers” and fantastically-invented counter-revolutionary parties? It is one of possible explanations, but it is not convincing: how to reconcile admittance of planning failures (implicit in the idea of diversions) with fulsome daily praises of what was accomplished? I know that one can square the circle by claiming that Stalin knew very well of the problems, that he knew that others knew, and that the way to explain problems away was to argue they were due to systematic sabotage. But because of the inconsistency I mentioned, it is, in my opinion, a weak explanation. Paranoia is not a good explanation either because if Stalin became paranoid in the last years of his life he certainly was not irrational nor paranoid in the mid-1930s. Every writer is impressed by how carefully planned and well-executed Stalin’s moves in intra-party struggles were. Why would he go mad in 1936?

This great puzzle is highlighted by comparison with Hitler’s purges. They were fully rational and understandable. Hitler destroyed SA, his most loyal servants, because he chose Wehrmacht over the SA; a thing that every rational politician would do. When he eliminated Rommel, Canaris and others, he did so because they were convincingly involved in the Stauffenberg plot to kill him. So, he lashed back in retribution.

In Stalin’s case, the logic escapes us. His punishment of “enemies” did not follow any predictable pattern where it would increase in relationship to the threat they posed to his power. Zinoviev, Kamenev, Tomsky, Rykov, all in exile, were no threat to him. Bukharin clearly chose to serve him. They were all previously thrown out the Party, then reinstated, and subsequently expelled again.

Stalin was considered to be an excellent Machiavellian. But he was not. Machiavelli accepts murders by the Prince but only insofar as they are needed to preserve his power, and so long as the Prince is aware that he is thereby engaged in an immoral act. Stalin failed on both accounts: he had no qualms about using the most foul means while not acknowledging them for what they were, probably not even to himself (although this is something that we obviously can never know). Nor is it at all demonstrable that the unremitting orgy of violence and killings that enveloped the Soviet Union and international Communist movement (whose many leaders were also killed in the purges) during these three years was in any way necessary for Stalin to remain in power. We are thus, as I mentioned in the title, left with one of the great puzzles of recent history: Why was all of this necessary?

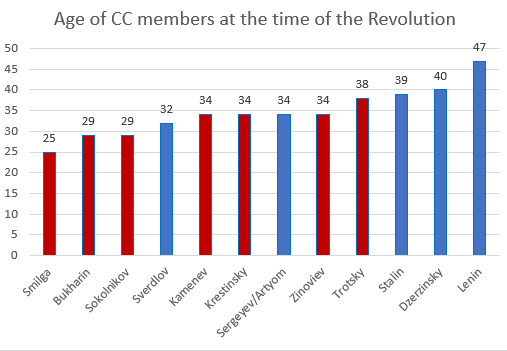

PS1. Some time ago I put together this graph to illustrate the relative youth of Central Committee members at the time of Revolution. The median age was 34. The youngest member was 25. But I also illustrated that more than half of the members of the Central Committee in 1917 (in red) were killed by Stalin. Others died before he could kill them.

PS2. My preferred recent biography of Stalin is by Oleg Khlevniuk, Stalin: New Biography of a Dictator. It is remarkably level-headed book, not given to exaggeration one way or another, based on newly-available sources and very well written. I wrote a review (link here) of a very interesting book by Russian historian Vladimir Nevezhin that documents Stalin’s banquets organized between 1935 and 1949. These were enormous affairs and the most honorific position was, of course, to be invited to sit at Stalin’s table. Out of 21 people thus invited, eight were shot and two killed themselves (to avoid torture). Generally speaking, Russian, or more generally Soviet, historians, in my view, compared to the foreign have the advantage of more direct knowledge of what the period of Great Terror involved because almost no family was spared, or failed to know somebody who was involved. Roy and Zhores Medvedev, with their intimate knowledge of many protagonists, as shown in their monumental Let History Judge, fall in that category. Often, same families had, within its ranks, the executioners and the victims. That level of personal, immediate and difficult-to-transmit knowledge is in instances like this irreplaceable. We know it from Thucydides and Tacitus onwards.

Be the first to comment