CDOs’ were widely blamed for fuelling the financial crisis. Now similar instruments called ‘CLOs’ are in the ascendance. Is it time to start worrying?

Adam Leaver is a senior lecturer in Financial Innovation and Business Analysis at Manchester Business School.

Daniel Tischer is a Lecturer in Management at the University of Bristol.

Cross-posted from Open Democracy

A crisis the scale of the 2007/8 banking collapse required a dismantling of the intellectual, regulatory and financial networks at its core. When networks are not broken up, systems and behaviours tend to reproduce themselves. It was therefore no surprise when, soon after the crisis, securitization was again extended as the only viable solution to any number of economic problems, from the funding of SMEs to the rekindling of corporate investment. Handed a rare, fleeting moment of reconstructive possibility, our political classes and technocrats, in consultation with the banking lobby, chose to try to recreate 2006 – the pinnacle of the Goldilocks economy, forgetting the bear economy that followed.

There are strong indications that today’s economy may be entering the equivalent of its 2007/8 phase. A recent article in the Financial Times reports that the Financial Stability Board has launched a review of the leveraged loans market – a market which has boomed over the last five years in large part due to demand from collateralized loan obligations or ‘CLOs’. These securitization vehicles bear an uncanny resemblance to the Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) that drove much demand for sub-prime mortgage backed securities before 2007.

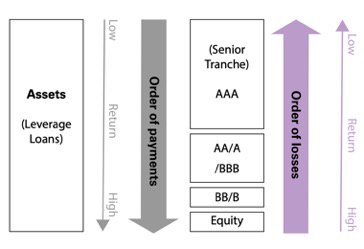

A CLO has a pool of leveraged loans or similar low-grade securities which are its assets or ‘collateral’. Leveraged loans are like corporate ‘sub-prime’ loans – they are made to below investment grade companies, i.e. companies with a credit rating below BBB-/Baa3. This lending is financed by the sale of different tranches of securities which are the liabilities of the CLO. The investors who buy CLO securities are paid in a predetermined order – the holders of the lowest risk tranche (the AAA rated tranche) get paid first but receive the lowest rate of return; only after that point does the next tranche get paid and they receive a higher rate of return because they hold more risk, and so on. At the bottom of the waterfall structure is the ‘equity’ or ‘first loss’ tranche. The tranches receive interest and principal payments based on interests and other cash flows that the CLO collects from its pool of loans (Figure 1). CLOs work on the same alchemic principle as CDOs – the ability to convert trash into gold.

Figure 1: CLO Risk, Return and Priority of Payments

Source: Natixis Asset Management (2017)

To understand the relation between CLOs and leveraged loans, it makes sense to turn the value chain on its head. Most people assume that demand for loans by companies drives bank lending, which sets the limits of what can be securitized. There is some truth in this, but it does not entirely explain the market drivers. Demand from investors for CLO securities also drives demand for those leveraged loans which in turn collateralize CLOs. This may encourage banks to source more collateral for CLOs by lowering their corporate lending standards – for example by reducing or removing covenants, lending to riskier borrowers or even cutting (risk-weighted) interest charges. These actions by lenders will, all things being equal, increase the pool of willing borrowers and so provide more loans to securitize. But that may also increase the risk of defaults and default correlation, which as we know from 2007/8 can create all kinds of problems. Should alarm bells be ringing?

The industry makes much of the difference between CLOs and CDOs. They stress that refinements have been made to the models and risk management structures and that the underlying collateral has a different risk profile. They claim that the rating agencies have revised their rating methodologies, leading to smaller AAA rated tranches and larger equity tranches, with higher margins for AAA notes. It has also been argued that retention rules mean that collateral managers now must have ‘skin in the game’ when they act on behalf of CLO investors, removing moral hazard. Proponents also point to the different default rates between CLOs since 2008 and CDOs before 2008, and the different position of leverage loans in the corporate credit structure.

But there are reasons to be wary.

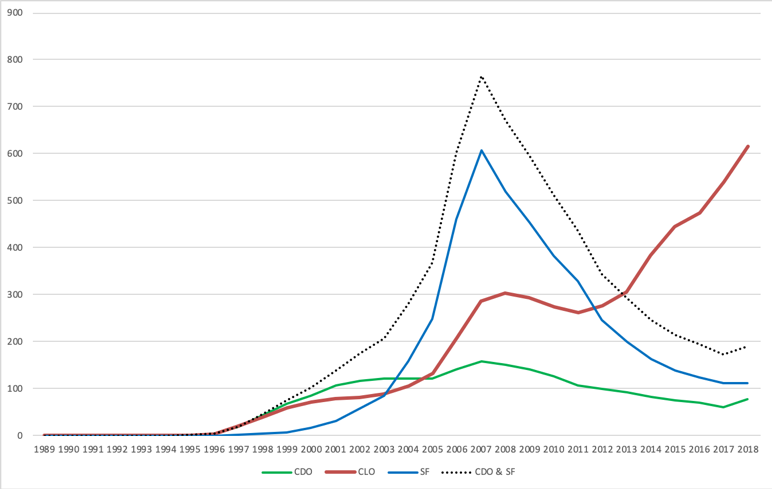

First, CLO volumes in 2018 are at (roughly) where CDO volumes were in 2006, according to Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) data. Default rates on CLOs in 2018 are currently low, but they were low on CDOs in 2006, and we know what happened next. The default performance of CLOs may therefore be contingent upon the business cycle, rather than the innate attributes of the security.

Figure 2: CLO and CDO/Structured Finance Amounts Outstanding (US$bn)

Source: SIFMA (2019).

Second, what happens next depends on how far-reaching those industry refinements have been. In our view, CLOs have more in common with CDOs than there are differences. The much-maligned pricing models are broadly the same. Similarly, both CDOs and CLOs use historic default data to calibrate their future default assumptions. This ignores the interactive or counter-performative relation between the models and default outcomes: that the application of the models using low historic default rates creates complacency. This can encourage lenders to issue riskier loans, which, when they go wrong, lead to much higher default rates and default correlations than was evident historically. For example, the percentage of leveraged loans classified as ‘cov-lite’ is now around 80% compared with just 30% before the last crisis.

Third, the ‘skin in the game’ adjustments mis-read the problem and have now been watered down in any case. Although collateral managers were required to hold some stake in the structures they managed, some did this voluntarily in the last crisis. In some cases this caused them enormous problems, as in the infamous Abacus CDO. The risk is not that collateral manager and investor interests become mis-aligned, but rather that collateral managers are unable to pick winners in a context where collateral quality declines universally across the asset class.

Finally, the reforms did not address the fundamental problem: that the temporalities of returns and risks are out of sync when elite employees are paid on a ‘Day One P&L’ basis. This accounting method allows bankers to be paid today for the arrangement of a securitization, even though the income streams that securitization may (or may not) remit many years later. This leaves bankers with the bonuses today and future risks with the CLO security buyers, or even their own banks. This inter-temporal moral hazard explains the willingness of bankers to ignore diminishing collateral quality to a greater or lesser extent.

There are some reasons to believe that CLOs could be even more risky than CDOs. For example, achieving diversification in a portfolio of leveraged loans may be more tricky than in mortgage markets, because of the stronger interconnectedness of companies across industries. Leverage can also be used to pay out dividends to shareholders, which hollows out firm equity buffers.

However, the most salient, and from our reading under-acknowledged, problem relates to recovery rates. Leveraged loans, like mortgages, are in most cases secured – creditors have a claim on the borrowers’ asset in a default event. The recovery rate (i.e. the amount a creditor expects to recoup upon seizing an asset and reselling it in the event of default) plays a key role in the pricing of CLOs, because payments into the structure do not stop if the majority of the money from the loan can be recovered in the event of a default. Hence with CDOs, banks could seize the house from a homeowner in default, resell it and recover most of the cost of their loan. A good recovery rate therefore allows structurers to create a larger amount of AAA paper – which is a key aim of the securitization. However, houses and companies are very different entities because companies are a combination of tangible and intangible assets. Firms have ‘goodwill’, an intangible asset which is created when a firm buys another firm – it is the difference between the acquired firm’s book price and the market price paid by the acquirer.

Leveraged loans are often used to make these acquisitions. And in this period of loose credit, partly driven by CLO demand, firms are paying much higher multiples of annual net profit for their target firms. In many cases, this means that firms are carrying much more goodwill than they ever have done historically. When you combine cov-lite leveraged loans, which limit a creditor’s capacity to recover assets early, with an increasingly intangible balance sheet, then there is a risk that when things start to go wrong one of two things can happen.

First, if the abundance of cheap credit has encouraged overpayment for M&A targets, a large goodwill impairment will suddenly reduce the net asset value of the firm, limiting what can be recovered by creditors. Second, covenants may be so light that firms close to bankruptcy sell assets to pay shareholders, leaving creditors with nothing to recover – a phenomenon described well in Akerlof & Romer’s paper on looting. At the moment recovery rates are assumed to be around 70-80%, depending on which publication you read. That seems wildly optimistic.

The current risks in the CLO market and its effects on credit markets are underappreciated; as are the parallels with the pre-crisis CDO market. Perhaps that is to be expected – a defining feature of late capitalism seems to be its capacity to forget. After all, when you have the same people in the same decision-making positions, or people who share the same ideas in those positions, forgetting is the first stage in a rinse and repeat profit cycle, where there is no downside for the protagonists.

Be the first to comment