The Basque coastal hotspot San Sebastian is the most expensive city in Spain; a virtual feeding frenzy for rentier capitalism that is driving away its young people. The Basque Government, however, remains unmoved

Ben Wray is a freelance journalist based in the Basque Country, and co-ordinates BRAVE NEW EUROPE’s Gig Economy Project. He is co-author of ‘Scotland After Britain: The Two Souls of Scottish Independence‘ (Verso, 2022).

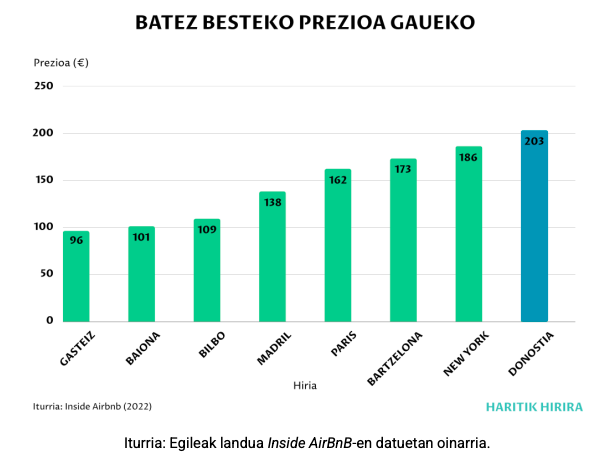

What is the most expensive city for renting an AirBNB? Not London. Not Paris. Not even New York. It’s San Sebastian (called ‘Donostia’, in the Basque language).

The graph (in Basque) is from the Haritik Hirira collective, which published a study on AirBNB in San Sebastian at the start of this year.

“For the prices to be even higher than New York, this was even surprising for us,” Josu Del Campo, one of the study’s authors who was brought up in Donostia and now lives in Barcelona, tells Brave New Europe.

Haritik Hirira’s report shows how AirBNBs have bounced back in the Basque city following the pandemic. At their lowest point in 2020 there were 1311 AirBNBs listed in San Sebastian, before rising to 1659 in 2022. The latest ‘Inside AirBNB’ data shows 1,811 listings, just short of the peak level of 1852 in 2018.

“The most AirBNBs is always July to August, so we can expect it to increase more,” Del Campo says. “We knew when we did this study that if they don’t take any measures to stop this, it’s going to keep increasing every month.”

Happy days if you are a landlord renting your properties on AirBNB, and why wouldn’t you? Tourist flats generate three times as much revenue as residential private rents in Donostia, a city that is the second most expensive in Spain to rent a home.

Indeed, so lucrative are the tourist licenses that some speculators are known to have acquired them without any intention of ever renting the property out to tourists, safe in the knowledge that the value of the property is higher with a license in hand. When houses are commodities, a governmental stamp of approval to rent-seek from backpackers is gold-dust.

But whereas the speculators and landlords see Euros flashing before their eyes when tourists come to town, for locals the tourist increasingly symbolises displacement. Basque Government data shows thousands of young people have left the city over the past decade in search of a house they can afford.

“I say to my friends that when you walk through the centre of the city you hear French, English, you don’t hear Basque and you don’t feel at home,” Jon Macías, the other author of the Haritik Hirira study who lives in the city, says. “I don’t live in the centre and I prefer not to.”

“I am 27 and all of my friends who live in Donostia, they still live with their parents and they are working,” Del Campo adds.

Asset price inflation

The AirBNBification of Donostia should be seen in the context of the city’s skyrocketing asset price inflation. Not only does San Sebastian have the highest house prices in Spain, average houses are worth 22% more than the next most expensive city (Barcelona), 26% more than Madrid and 39% above Bilbao, just an hour’s drive away. Average prices are half a million Euros. No wonder it has been described as ‘una ciudad para ricos’.

Part of the explanation is that Donostia’s tight geography – caught between the sea on one side and mountains on the other – means that the typical urban sprawl of most modern cities has been to some extent constrained.

“It is true that the very configuration of Donostia as an urban element is conditioned by the different natural elements,” Ricardo Burutaran, a councillor in the City Council for Basque left nationalist coalition EH Bildu and an expert in urban planning, tells Brave New Europe. “We have always defended that the development has to adapt to the terrain. Obviously it is necessary to build, but when we are limited by space there is more necessity to plan very carefully the already-existing urban environment.”

Instead, the domination of market forces in a confined geographical space has seen the price of land and property accelerate out-of-control. Under the leadership of mayor Eneko Goia since 2015, the city council has prioritised hotels and big events venues. Over 50 hotels have been built in the city in under a decade.

Goia, a member of the centrist Basque Nationalist Party (PNV), claims that there was a “capacity deficit” in the city which required such a rapid growth in accommodation and hospitality, admitting that “perhaps what has happened is that the process that in other cities has taken twenty years to develop, in Donostia has taken ten.”

As for run-away house prices, Goia says its a “structural problem” and a “general phenomenon”, in which all “a city Council can do, I believe, is to create more supply”.

But the supply of housing is not just about what is added, but also what is taken away. Every AirBNB is one less property for residential use, and every hotel and conference venue is one less piece of land in which housing could be built.

Moreover, where new houses are built, under what type of ownership and with what sort of community amenities are just as important as how many. Burutaran finds that the periphery of Donostia is becoming hollowed out by its hyper-touristic centre.

“Many big businesses are concentrated in the centre, and this is contributing to the desertification of certain areas of the city where there is absolutely no commerce,” he says. “We are creating neighbourhoods that have nothing except housing.”

As the city is gentrified and becomes increasingly geographically segregated, it should be no surprise that those who gain from AirBNBs are almost exclusively in the wealthier parts of San Sebastian. Sixty-five per cent of AirBNBs are in just two hotspot areas, ‘Gros’ and the centre. The lowest-income areas have under 1 per cent of AirBNBs.

“Donostia is still not at the same level as some big tourist cities in terms of the total number of AirBNBs per population, but in the few neighbourhoods where the AirBNBs are really concentrated, it is at this level,” Del Campo explains.

So much for AirBNBs providing a supplementary income for those who need it, as the platform’s CEO Brian Chesky has argued. Another one of his favourite claims is that AirBNB hosts are not run by businesses with multiple properties – they are just ordinary folk making best use of their extra space. Not in San Sebastian: 68% of available AirBNBs are owned by hosts with two or more properties, up from 61% in 2017.

“The AirBNB market in the city is a lot more about businesses now than it was before,” Macías says.

Isn’t everything?

The politics of property

Goia is standing for re-election in the local elections this Sunday [28 May]. Aware of growing discontent over the city’s over-tourism, the mayor announced a one-year suspension to new tourist licenses just two months ago. Del Campo believes the pre-election announcement is not all it seems.

“There are already hundreds of licenses which they are just now approving, so the new suspension will not include those licenses,” he says. “The number of AirBNB apartments will still increase.”

The lack of any real desire to take substantive action on Donostia’s housing crisis is indicative of the politics of PNV. The dominant party in Basque politics in the post-dictatorship era, PNV can always be relied on if you are a landlord or a big business in ‘Euskal Herria’.

The Basque Autonomous Community is one of the most expensive in the Spanish state for house prices and rents, but PNV have refused to apply a 2015 Basque housing law which would expropriate empty homes from banks and, just last month, sided with Spain’s right-wing parties in voting against a new housing law in the Spanish Parliament.

The PSOE-Podemos coalition government’s housing law, which was passed due to the votes of EH Bildu, gives the regions and municipalities the power to apply a 2% limit on rent increases in ‘stressed’ areas this year and 3% next year. Bildu are the main challengers to PNV in Donostia, and their candidate Juan Karlos Izagirre, who was mayor of the city from 2011-2015, has said he would apply the rent limit immediately across the whole of San Sebastian if he wins.

Better than inaction, but a rent restriction will be small comfort for many ‘Donostiarrians’, who as well as facing rising food and energy prices have seen rents increase by 7% in each of the last two years. The new housing law also had nothing to say about tourist flats, despite their rapid revival across Spain post-pandemic. As for house price inflation, the sort of taxes and credit restrictions which could place serious controls on the property market are not up for discussion in Madrid.

This is the politics of property: while everyone in theory accepts there is a problem, especially in tourist cities like San Sebastian and Barcelona, solutions range between token gestures and sticking plasters on gaping wounds. There is no political appetite to upset the apple cart of perpetual growth in asset values.

Perhaps it’s asking too much to expect governments to prick the bubble of asset price inflation, at least without a substantial push from the asset-less. We have seen the stirrings of such a revolt in cities like Berlin, and in San Sebastian the week before the election a ‘Donostia not for sale’ protest took place.

The unpropertied will have to get organised if they want the right to the city – they’ve nothing to lose but their scandalously expensive tenancies.

Thanks to many generous donors BRAVE NEW EUROPE will be able to continue its work for the rest of 2023 in a reduced form. What we need is a long term solution. So please consider making a monthly recurring donation. It need not be a vast amount as it accumulates in the course of the year. To donate please go HERE.

Be the first to comment