The G-7 Summit in Hiroshima, Japan has been used to ramp up western aggression towards China. History and geopolitical reality tell us that the US is a much bigger threat to world peace than China is ever likely to be

Ben Wray is a freelance journalist and co-ordinator of BRAVE NEW EUROPE’s Gig Economy Project. He is co-author of ‘Scotland After Britain: The Two Souls of Scottish Independence‘ (Verso, 2022).

IT’S an interesting fact of history that although the European colonialists were the first maritime powers to subjugate foreign populations, they were by no means the first to dominate the seas.

In the early fifteenth century, Chinese admiral Zheng He’s voyages, which reached as far as modern-day Saudi Arabia, were navigated by ships well in advance of anything European nations could produce at the time. For four and a half centuries, China was the world’s leading maritime power, but by the time the Europeans were enslaving large parts of the global south and growing rich out of their resources, China had long since abandoned its seafaring ambitions.

There are various reasons for China’s ‘isolationist turn’, but fundamentally it was about how Chinese elites envisaged the country’s development.

“Although large numbers of Chinese migrated to South-East Asia, the Chinese state, unlike the European nations, showed no interest in providing military or political backing for its’ subjects overseas endeavours: in contrast, the Qing dynasty displayed great concern for its continental lands in the north and the west, reflecting the fact that China saw itself as a continental rather than maritime civilisation,” Martin Jacques writes in ‘When China rules the world’. “Ironically, it was the European powers that were to begin the colonisation of South-East Asia, especially from the mid-nineteenth century.”

History could have turned out very different if China decided to build on Zheng He’s voyages and expand outwards. Perhaps the Chinese would have developed the same ‘missionary’ zeal that European colonialists used to rationalise their foreign plunder and subjugation, a paternalism that remains strong among the apologists for western imperialism today.

As it is, China’s “continental civilisation”, as Jacques puts it, remains ruthless in the forced assimilation of its periphery – see the Uyghurs and the Tibetans – into the Han Chinese dominated centre, but it has never had ambitions to conquer nations in distant lands. Beyond the countries which it borders, China has no track record of backing up its economic muscle with military interventions.

The future never replicates the past, but it does offer us insight into the sort of world power China is and will be. While the United States – which was forged through settler-colonialism – has sought to impose ‘free-market’ capitalism all over the world through endless wars and institutions like the World Bank and IMF, China’s relationships with other nation-states have been coldly transactional, marked by a remarkable disinterest in the ideology of their interlocutors. Many westerners view Chinese foreign policy as amoral, but if you are in Chile or Iraq or Libya, a policy of domestic non-interference may appear infinitely preferable to western meddling.

The Chinese can be ruthless in their business dealings with foreign states, and the tendency of Chinese firms to bring their domestic workforce with them when delivering big infrastructure projects abroad often riles local populations. However, when contrasted to the punishing debt obligations of western capital and the disastrous IMF ‘structural adjustment programmes’ imposed on debt nations, is it any wonder that many states in the global south are now far keener to work with China than their Western counterparts?

The fact that an alternative to the west for finance and investment now exists is emboldening many of the world’s poorest nations, which would have previously had to suck up whatever the neo-colonialists were feeding them. Witness German ambassador Herbert Beck being given a dressing down by Namibian President Hage Geingob, after Beck complained about the fact that there are four times as many Chinese in Namibia as Germans. The President of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Felix Tshisekedi, was similarly frustrated by French President Emmanuel Macron’s “paternalistic” tone in a recent joint press conference, reminding Macron that “Francafrique no longer exists.”

There is no need to be gooey-eyed about Chinese power in the world: Xi Jinping’s regime is state-capitalist with its own geopolitical interests. But those interests motivate China towards a different vision of the world to that of the United States, as Wolfgang Streeck has recently pointed out. Whereas Uncle Sam’s project is a new “bipolar order” – maintaining its position as the hegemonic power in the majority of the world by containing China’s rise – China’s “geostrategic project, by contrast, seems to be a multipolar world”.

Streeck explains: “For reasons of both geography and military capacity, the goal of Chinese foreign and security policy cannot really be a bipolar order with China battling the United States for global dominance, nor a unipolar world with itself at the centre. As a land power bordering on a large number of potentially hostile nations, it needs first and foremost something like a cordon sanitaire, whereby its neighbouring countries are bound together with China by shared physical infrastructure, freely awarded credit, and a commitment to stay out of alliances with potentially hostile external powers – as opposed to the American desire to subject the world as a whole to a globalized Monroe Doctrine. (The United States has only two neighbours, Canada and Mexico, which are quite unlikely to turn into Chinese allies.)

“In addition, China actively encourages the formation of something like a league of non-aligned regional powers, including Brazil, South Africa, India and others: a new Third World which would keep out of a Sino-American confrontation and, importantly, refuse to join American economic sanctions against China and its new client state, Russia.”

It should not be forgotten that in this ‘new cold war’, America still retains overwhelming dominance militarily, if no longer economically. As Streeck adds, China “cannot be sure it would not lose a war against the United States” and as such it “would prefer to be seen as a neutral power among others, rather than one of two combatants for world domination”.

This imbalance of power helps to explain why American provocations are not matched by an equal and opposite response from the Chinese. Take the all-important case of US sanctions on Chinese use of advanced semiconductor technology. In a speech in September, US national security advisor Jake Sullivan announced that the US was abandoning its previous strategy of trying to stay two generations of chips technology ahead of China, and instead it would try to “maintain as large of a lead as possible”. What followed was a ratcheting up of semiconductor sanctions on China from the US and its allies, in an attempt to consign China’s 1.4 billion people to permanent technological inferiority. Beyond a strongly worded letter to the WTO, China has offered no direct response to American escalation*, despite the sanctions beginning to bite.

One need not have any sympathy with Xi Jinping’s authoritarian regime to see that it is the United States which remains by far the largest threat to peace in the world today. As the G7 gathered in Hirsohima, Japan this weekend, it was a reminder that US President Joe Biden’s predecessor, President Harry S. Truman, struck the civilian population of that city with a nuclear bomb some 78 years previously, the first ever use of a nuclear bomb in warfare, which was followed three days later by the US bombing of Nagasaki. Thankfully, nukes have never been used on civilian populations by any country ever since.

It was remarkable that the memory of one of the worst crimes of history – which killed between 90,000 to 146,000 in the first couple of months and many more from the effects of radiation long after – was used not for self-reflection by the United States, but to take aim at China. A White House statement failed to mention that it was the US that conducted the “atomic bombings of 1945”, before quickly moving on to take aim at “China’s accelerating build-up of its nuclear arsenal without transparency nor meaningful dialogue”.

Biden, who refused to offer an apology for the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima, sought to use the trip to East Asia to rally regional allies against China. Rahm Emmanuel, former chief-of-staff to President Obama and now ambassador to Japan, described it as a chance for “developing the tools to deter and defend against China’s economic intimidation and retaliation.”

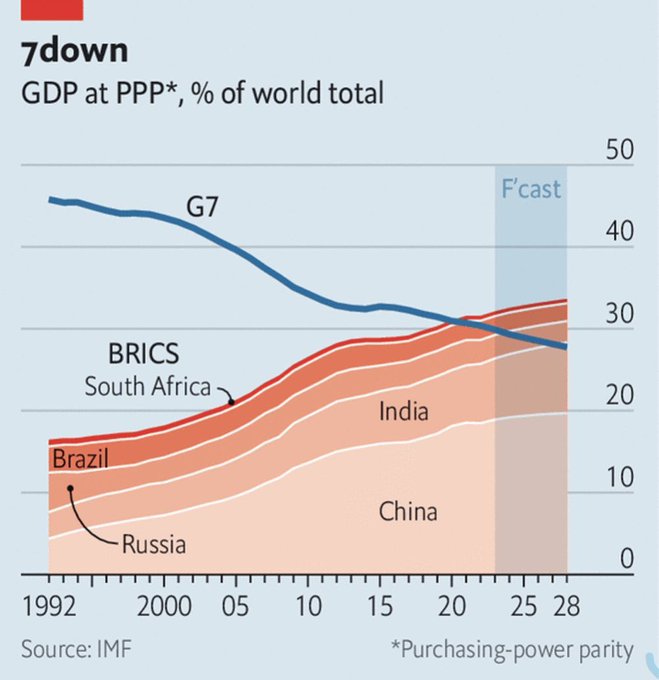

The fear that animates the G-7 is the fact that they are now smaller than the BRICS economically, a shift that will only accelerate in years to come. Indeed, China is economically as big as all of the G-7 combined, minus the United States. The G-7 are desperate to keep China down and will use US’ military superiority to do it.

While in the immediate term we should all be worried about the US backing fighter jets for Ukraine at G-7, crossing yet another red line, the bigger picture is all about China. History and geopolitical reality both tells us that when it comes to foreign wars, we should be much more worried about the old superpower in the West than the new one in the East.

*Shortly after publication of this article, China did finally retaliate to the US crackdown on Chinese semiconductors, in a significant move

Thanks to many generous donors BRAVE NEW EUROPE will be able to continue its work for the rest of 2023 in a reduced form. What we need is a long term solution. So please consider making a monthly recurring donation. It need not be a vast amount as it accumulates in the course of the year. To donate please go HERE.

One can add that the US looked rather nice until the end of WWII (provided you weren’t a Latin American). It behaved nice towards people who were subjugated by European colonialists, and posied itself as a future ally against these. And they really were, since the world was decolonized after 1945.

Alice Amsden even thought it behaved decently until 1975 (Escape from Empire, 2007). The countries of the world were free to do whatever they liked – provided they didn’t line up with the Soviet Union. It wasn’t until after the oil shock the US began to be really nasty.