France introduced a CO2-based bonus-malus system for new passenger cars in January 2008. The car buyer would either pay a fee (malus) for vehicle CO2 emissions above certain levels (as officially determined by the EU vehicle type approval procedure), or receive a rebate (bonus) if the vehicle’s CO2 emissions were below certain limits.

France is one of only a few countries to apply CO2-based fees and rebates simultaneously. This feebate system is one of the key tools that the French government is using to bring down carbon emissions from vehicles.

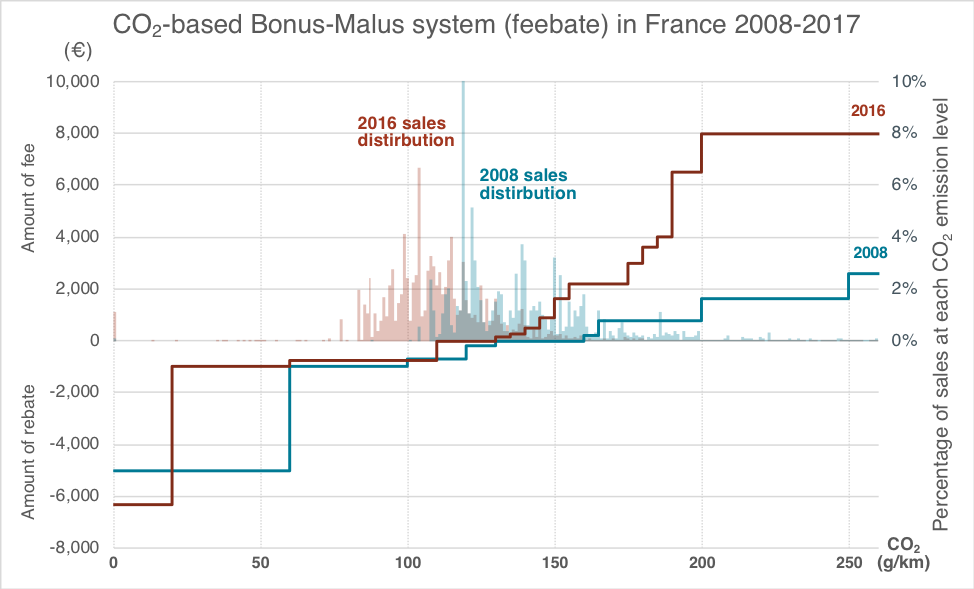

In the last decade, the French government has been adjusting this system. The chart below graphs the bonus or penalty (y-axis) against the vehicle CO2 emissions (x-axis). The CO2 emission levels at which the government starts to impose fees and provide rebates have decreased over the years, as have the CO2 “steps” between each category.

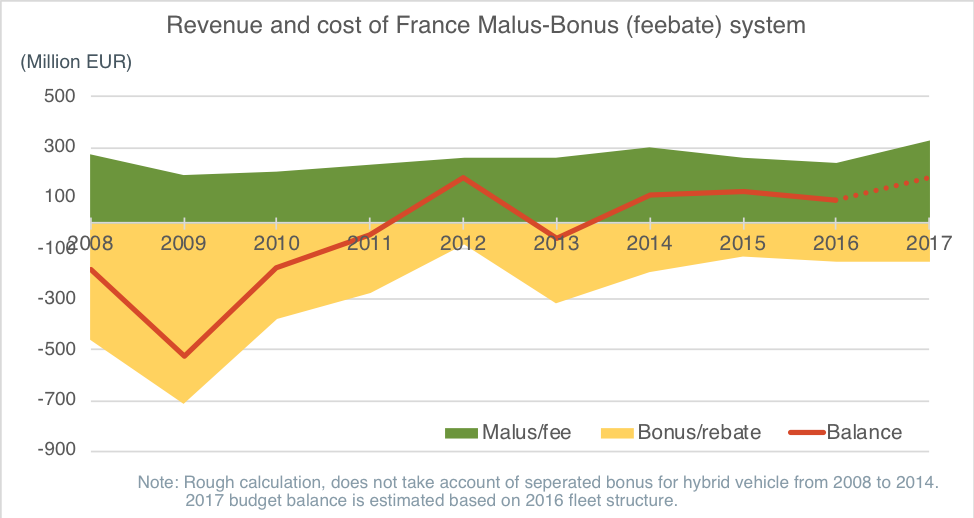

France pioneered this type of system, and the government had little empirical evidence to draw on in forecasting how it would work. They quickly discovered that they were paying out far more money in rebates than they had projected. They had accurately foreseen that as the fleet moved towards lower CO2 emissions, rebates would go up and fees would go down. But they did not anticipate a second dynamic. France used step functions to set levels of fees and rebates, and manufacturers quickly learned that they could greatly increase rebates by designing vehicles to register CO2 emissions during the type-approval tests that were just below the step function cut points. This led to a rapid increase in the rebates paid by France for relatively small CO2 emission changes.

France addressed these issues in two ways: by making annual adjustments to maintain a balance between fees collected and rebates paid, and by reducing the size of the steps to minimize gaming and improve the effectiveness of the system.

In response to the feebates, the EU CO2 standards, and other related policies, fleet-average CO2 emissions in France fell steadily over the past decade. Figure 2 compares the sales distribution of vehicles based on their registered CO2 emission level in 2008 and 2016. We can clearly observe the market transition toward lower CO2 emission vehicles. As more vehicles with lower CO2 emissions were sold to the market, the French government would have collected less in fees and paid out more in rebates if no adjustment were made to the feebate system. Figure 3 shows a rough calculation of the total fee and rebate streams, based on CO2 emissions of registered vehicles and the changing feebate schedules from 2008 to 2017. (Vehicle sales information comes from EU Vehicle Market Statistics Pocketbook.) The figure shows that in the first three years after the feebate system took effect, the French government struggled to find a good budget balance, in part because of manufacturers taking advantage of the step functions, and lost €300 million on average annually. As the government adjusted the feebate system, the income stream stabilized.

To minimize problems with manufacturers taking advantage of the step functions by engineering vehicles to qualify for larger rebates (or smaller fees) in exchange for only small improvements in CO2 emissions, France increased the number of steps and reduced the size of each step with each model year (Figure 1). Which brings us to the latest and most important change: in 2017 the French government changed the “fee” part of the feebate line from a stepwise function to a continuous function.

A continuous feebate function is more effective because it provides an uninterrupted incentive to improve vehicle efficiency. Instead of assigning the same fee to a range of CO2 emissions, which diminishes any incentive to improve the performance of vehicles that are not close to the next “step” where a lower fee would apply, the French system now establishes a continuous fee rate line for vehicles with CO2 emissions between 126 to 190 g/km. Any vehicle within that range will see a reduction in the “malus” fee for every gram by which its CO2 emissions are reduced.

A continuous feebate rate line also means that regulators only need to periodically adjust the pivot point (i.e., the CO2 level that divides fee and rebate) and the slope of the rate to make the system self-funding and sustainable. In addition, it is easier to estimate the fleet trend and budget stream with the continuous fee rate function as it is more straightforward to predict market reaction based on elasticity of the purchase cost of vehicles.

The 2017 revision moves the French feebate system toward a better design than almost all other countries that have a similar CO2-based feebate structure. As more countries contemplate feebate systems as tools to ensure sustainable financing while promoting electric vehicles or lower CO2 emissions (like Sweden, for example), they can profit from France’s experience.

Be the first to comment