Why efforts to limit tax competition should be at the centre of global economic policy cooperation, and about the role of trade agreements

Brad W. Setser is the Steven A. Tananbaum senior fellow for international economics at the Council on Foreign Relations

Cross-posted from the website of the Council of Froeign Relations

There is, now, I hope a growing recognition that tax avoidance has a significant impact on the structure of global supply chains—some “supply” chains also function as tax chains, with transfer pricing shenanigans allowing firms to shift profits to low tax jurisdictions.

This is obvious to anyone who has spent much time with the data on trade in pharmaceuticals for example.

More on:

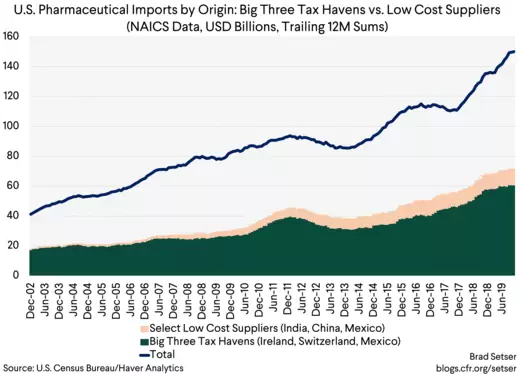

Ireland, Switzerland and Singapore account for 40 percent of the dollar value of U.S. pharmaceutical imports (using the NAICs data), while India, China and Mexico supply only 7.5 percent (by value).

These tax games appear to have only gotten more intense after the U.S. tax reform.

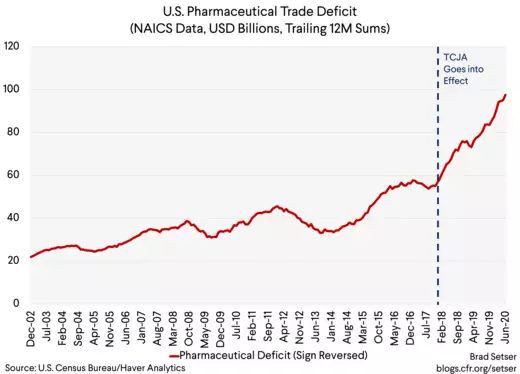

The U.S. trade deficit in pharmaceuticals is one track to go from just over $50 billion dollars at the end of 2016 to close to $100 billion by the end this year.

This reality has fairly obvious implications for U.S. tax policy—the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act created a clear incentive to shift profits offshore, and the related provisions of the tax code clearly need to evolve. There is the formal incentive created by the tax treatment of intangible assets*, but even more important is the opportunity, with enough tax engineering and actual production abroad, to shift the profit on U.S. sales of pharmaceuticals out of the 21 percent tax bracket.

But does it also have implications for trade policy?

After all tax—like currency for that matter—often drives trade outcomes at least as much as the set of issues that are often now at the center of a trade deal.

Elizabeth Warren, for example, suggested that the U.S. only do trade agreements with countries that participate in the OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Initiative (BEPS).

Simple enough. Yet it is possible to be compliant with the OECD’s initiative, as it now stands, and still be a center of tax avoidance. Ireland, for example, is ending double Irish structures as part of the BEPS process. But less will change than it would seem, as the tax structures that are replacing the double Irish continue to allow companies operating in Ireland to pay an effective Irish tax rate in the low single digits.

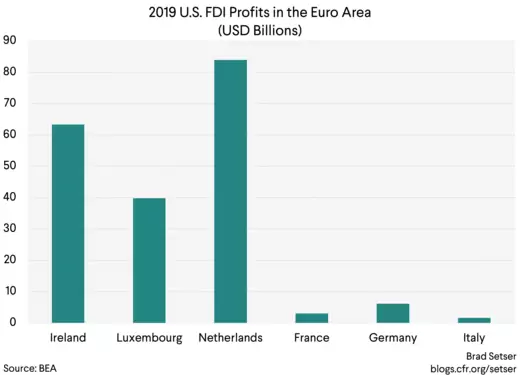

An even stronger standard would be to refrain from entering into any new trade agreements with any country that acts as a center for corporate tax avoidance—with centers of tax avoidance defined by a low rate of effective taxation on American subsidiaries and very high profits per employee. That though would mean no trade agreements with the EU until the EU convinces Ireland to make some significant changes to its tax code, and no trade agreement with a country like Singapore (which has long provided a tax home for certain U.S. semiconductor design firms it seems).**

The 2019 U.S. data on foreign direct investment leaves no doubt that U.S. companies systematically shift profits toward low tax jurisdictions—just consider the geography of the European profit of U.S. firms. It speaks for itself, and also broadly maps to the 2017 IRS country by country data.

If avoiding trade deals with centers of corporate tax avoidance is too onerous, there is another potential approach—one that mirrors in some ways the approach taken to currency provisions in the USMCA—namely full disclosure of the tax treatment of U.S. subsidiaries operating in all trade agreement partner countries.

The disclosure could be modeled on the Internal Revenue Service’s country-by-country reporting on the offshore profits of U.S. firms for example, with new disclosure from the host country of aggregated data on the tax treatment of U.S. subsidiaries operating in offshore jurisdictions. The basic idea is simple: countries that are facilitating tax avoidance by U.S. companies would have to disclose that fact, and it in turn would hopefully become the subject of discussion in other, tax focused foras.

New trade agreements could also be conditioned on full compliance with the OECD’s BEPS principles and, if agreement is reached, the OECD’s new Inclusive Tax Framework. If failure to participate in international efforts to limit tax competition meant automatic loss of the benefits of trade agreement (reverting to WTO tariffs for example), that would generate a significant automatic sanction.

I suspect there are other ideas as well.

Of course, the United States could do a lot to limit tax avoidance simply by changing U.S. tax law in ways that reduce the incentive of U.S. firms to take advantage of low tax jurisdictions abroad. Tax avoidance by U.S. companies is as much a function of U.S. policy as the result of say Irish or Singaporean policy. But there is, by now, I hope growing agreement that efforts to limit tax competition should be at the center of global economic policy cooperation, not at the periphery.

* The Global Intangible Low Tax Income (GILTI) provisions allow companies to deduct a deemed return on their tangible assets abroad from their global minimum payment (hence the “intangible” part of the provision’s name). The Foreign Derived Intangible Income (FDII) provision reduces the tax on the export revenue of U.S. companies if the company retains its intellectual property in the U.S. but shifts its tangible assets (like factories) abroad. See Kysar or Clausing for the details. But the biggest incentive to shift pharmaceutical production abroad is simply to create a tax structure that allows a U.S. based firm to shift the profits on U.S. sales of patent protected medicines into the lower offshore tax rates, not the formal treatment of tangible assets. Abbvie’s low effective tax rate would not be possible without offshore production.

** When Qualcomm wound up its overseas tax structure after being, apparently, caught up in the BEAT and instead opted to onshore its intellectual property and take advantage of the low tax rate on the export of intangibles (Qualcomm is fabless so at it exports are designs and the rights to its patent suite) it checked a box and turned its old Singaporean subsidiary into a branch … the disclosed unwind in turn helps lay out Qualcomm’s old tax structure, which other chip designers likely still use. That at least is my suspicion, but I am happy to be corrected. Qualcomm disclosed that “In fiscal 2018 and 2017, the foreign component of income before income taxes in foreign jurisdictions consisted primarily of income earned in Singapore” and “During the third quarter of fiscal 2018, we entered into a new tax incentive agreement in Singapore that results in a reduced tax rate from March 2017 through March 2022, provided that we meet specified employment and investment criteria in Singapore. Our Singapore tax rate will increase in March 2022 as a result of expiration of these incentives and again in March 2027 upon the expiration of tax incentives under a prior agreement. During fiscal 2018, one of our Singapore subsidiaries distributed certain intellectual property to a U.S. subsidiary reducing the benefit of these tax incentives almost entirely going forward”

Be the first to comment