Discussions just leave the participants where they were before. Or worse, lead them further apart.

Branko Milanović is an economist specialised in development and inequality. His newest book is “Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the World”. His new book, The Visions of inequality, will be published October 10, 2023.

Cross-posted from Branko Milanović’s blog

Over the years I have had political and ideological discussions with at least three groups of people and have concluded that these discussions are, almost entirely, futile in making people either see things differently, or acknowledge that others may see things differently, or -God forbid– change their opinions however slightly. That of course opens the question how people come to hold certain political and ideological positions—since at some level they must be influenced by views of others: their parents, family, school, and even random interlocuters. I do not have a good explanation for that. I think that reading, watching, listening and thinking does lead people to form and then to change opinions but I am very sceptical that direct discussion does it. The former methods are indirect: one reads an author and finds him convincing; but if one has a discussion with somebody acknowledging that that person has produced valid arguments appears to diminish him compared to the other person, and one’s intellectual vanity does not wish to accept that. Hence, I think, discussions almost never lead toward some genuinely-felt greater similarity of opinions. They just leave the participants where they were before. Or worse, lead them further apart.

For the participants who are more passionate or involved in the discussion, such an outcome is more frustrating. They therefore dispense a much greater amount of intellectual, mental and ultimately physical energy in trying to convince the other side—without success. They thus spend hours reviewing the arguments made, look for possibly better ways they should have presented their case, explore the weaknesses of the opponents as if any of that would make any difference. They waste their time and energy.

The three groups of people with whom I had chance (or misfortune) to have discussions and found impossible to move even a millimeter away from their held beliefs were Stalinists, nationalists and liberals. But their way to discuss things was different from each other. They were all equally unyielding in their views, but adopted somewhat different tactics.

Stalinists whom I had the “privilege” to discuss chronologically first introduced me to the type of discussion tactic that were used by the other two groups too. To any strong argument from the interlocutor they would produce either a denial (such and such event never occurred; there is no evidence; it was somebody else’s propaganda etc.), or they would accept that the uncomfortable fact occurred, but will justify it by an even greater perfidy of the other side. As I mentioned, I would see exactly the same arguments used by nationalists and liberals too. One advantage that Stalinists had compared to the other two groups (and that is the advantage of which I became aware much later on) is that they respected the knowledge of communist history. So, if you attacked them, they would produce the denial and perfidy arguments, but would respect your knowledge. They might even ask you about the fact they did not know. Communism thus functioned entirely like a religion. Christians have been at each other throats since the religion was founded: but the knowledge of finer theological or historical points was respected by the different sects even when they disagreed on almost everything else.

Political discussions with nationalists can, I think, best be described as throwing pebbles against an immense rock. You can throw as many pebbles as you wish, the rock will not be hurt nor moved. Like Stalinists they use denial and perfidy of others commonly, but perfidy of others now spreads to everybody under the sun except their favored nationality. In that sense, perfidy was much more widespread than for Stalinists since perfidy included n-1 national groups in the world. Moreover, if you bring two opposite nationalists together, since they both believe that n-1 groups are all equally at fault, the conclusion is that it suffices to have only two of them to prove that the entire world is evil. Thus one quickly establishes the conclusion that in nationalists’ worldview it is ultimately the human nature that is evil since no nation can be exempt from it and the individual characteristics do not matter as they are determined by one’s ethnicity or race.

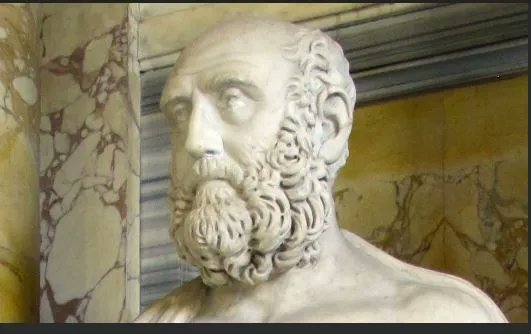

The third immovable group are liberals. They tend to be more sophisticated and more knowledgeable but this does not make them more intellectually honest. Actually, one could say the reverse because they handle sophistry with exquisite skills. Greek rhetorician Aelius Aristide’s comment from 1,900 years ago regarding Cynics applies to them: “They deceive like flatterers, handle insults like superior men, combining the two most opposite and repugnant vices: vileness and insolence.” They also use denial and perfidy of others as arguments, but they find them “served alone” to be too crude. That’s where sophistry kicks in. To any incontrovertible uncomfortable fact they do not produce just a denial, but shift the discussion on secondary or tertiary matters of marginal relevance to the topic discussed. That produces huge frustration in the interlocutor. It is akin to playing a soccer game which one is winning 3-0, but the other side refuses to acknowledge the defeat arguing that what really counts is the number of shots on goal, or free kicks or any other marginal statistics which is in their favor. All attempts to drive the discussion back to the original topic, and to the argument to which they have no valid counterpoint, fail in the face of this intransigent tactic which consistently shifts the realm of the discussion elsewhere.

Since liberals are more sophisticated than the other two groups they also use “rope-a-dope” tactic where, faced with uncomfortable truth, they do not reply to the argument but just shrug it off as irrelevant: “everyone knows that things are like that”. This again has a very negative effect on the interlocutor as it seems to present him as a very naïve person who takes the ideological stance of liberals seriously. In reality, they say, even if not loudly and clearly, flexibility is all: we may do things one way one day, and entirely differently the next day, but ideologically we shall always claim to be unswervingly loyal to our beliefs.

I have not had much occasion to discuss issues with true conservatives (who may not be vulgar nationalists) nor with the new generation of woke liberals, so I cannot tell how their tactics may differ from the ones that I mentioned.

I have thus come to the conclusion that if one believes in a certain point of view and yet has a limited amount of mental energy, it is entirely wasteful to use it in trying to convince others in direct discussions. It is much more effective to write and read and listen than to have Socratic or any other dialogues. They, I think, lead nowhere.

Be the first to comment