Ecolibertarianism is a political philosophy that offers a distinctly different response to the environmental crisis than the agenda being promoted by global elites

Jem Bendell is Professor of Sustainability Leadership, University of Cumbria, UK. He has recently published the book ‘Breaking Together – a freedom-loving response to collapse’

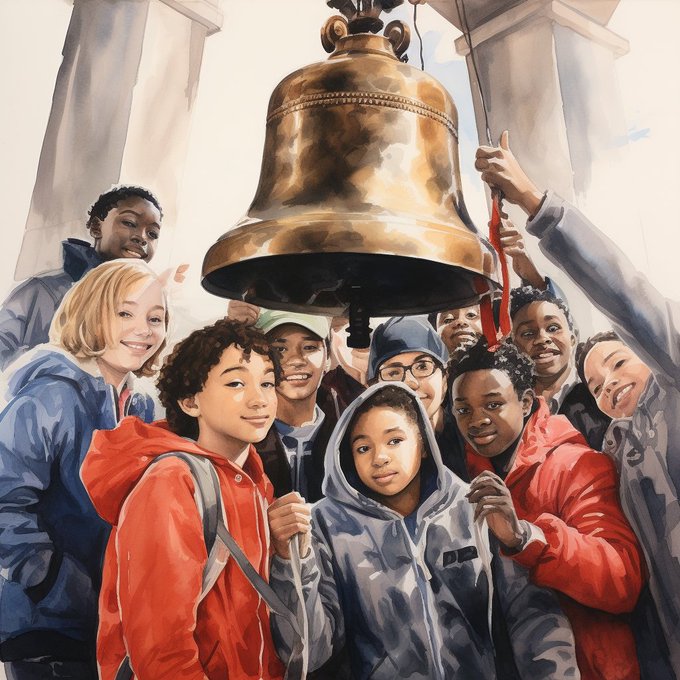

Image by Jem Bendell using Midjourney

In some of my interviews about the book Breaking Together, I have been asked what I mean by a freedom-loving response to our times, and what, specifically, I mean by ‘ecolibertarianism’. For some people concerned about climate change, to speak of freedom in relation to nature could seem rather strange. Especially as most environmental groups avoid saying much about politics. Instead, most of them express hope that we can fix the climate and ecological crisis by reforming society. You might recognise the components of their reformist agenda as technological innovation, entrepreneurship, philanthropy, large state subsidies for renewables, public education, far-off bans on combustion engines, and the censorship of content deemed by powerful institutions to be ‘misinformation’. Unfortunately for all life on Earth, including us humans, little has been achieved through that reformist agenda dominating environmentalism over the past 30 years. Worse, it is now triggering a backlash against state overreach and big tech control of our lives. Unfortunately, the fact their efforts have been useless-to-counterproductive, matters little to the ‘fake green globalists’ as they enjoy their dubious moral backslapping at fancy eco-branded events in New York, Davos and elsewhere.

Ecolibertarianism is a political philosophy that offers a distinctly different response to the environmental crisis than the agenda being promoted by those global elites. The people I regard as ‘ecolibertarians’ have concluded that societies destroy their eco-social foundations because the self-interests of the powerful are institutionalised to either coerce or manipulate us to experience life as unsafe and competitive. That means more of us cope by becoming more unthoughtful, uncaring and acquisitive. So rather than arguing that authorities and powerful groups should do whatever they decide to try to save the world, ecolibertarianism supports our freedom to care for each other and nature.

That describes a people’s environmentalism, and it is alive and well in communities around the world. In my book I describe people from Madison to Mombasa and Toulouse to Cape Town, who are working towards re-localising their economic activity with the help of local exchange systems that communities control themselves. These efforts mean that people are locally sourcing more healthy and affordable fresh food, accessing help with their care needs, and leaking less money from their local businesses into global corporations. Such initiatives are often small-scale and rely on committed volunteers. With help, their efforts could combine into an ecolibertarian agenda for a ‘great reclamation’ of our power from that merger of corporate and state power which plagues so many countries. It is a merger that reflects the ideology of ‘Imperial Modernity’. That is a bit of a grand term for the interlocking set of political, economic and cultural systems that shape our everyday lives to favour the accumulation of power by elites. It explains why, whatever the issue or crisis, and whatever the government, the elites always benefit the most. If we could reclaim our power from that system, we would finally have the chance to live in ‘ecofreedom’. By that, I mean the individual and collective state of being free and enabled to care for each other and the environment, rather than coerced or manipulated towards behaviours that damage it.

In the US city of Philadelphia there hangs a bell, with a crack running through it. Due to its association with the United States’ Declaration of Independence, that Liberty Bell is a symbol of freedom. And just like the bell, there has been a fracturing of our liberties as societies are disrupted, impoverished and manipulated. Our collective commitment to freedom also risks breaking. Because we are told by mainstream media that concerns for personal liberties are selfish, rather than being key to our solidarity against exploitation. I have lived most of my adult life outside my country of birth. I have noticed that outside of Western countries, the goal of liberty is more quickly recognised as a collective endeavour to thwart oppression. In the West, however, people are being misled by the media that there could only be a narrow and partisan version of liberty to defend. It’s time to reclaim the concept as well as the practice of freedom. To do so, we must recognise the environmental context we live within today, and the impediments to us all responding to that as our best selves. That is where ecolibertarianism moves beyond the narrow and incomplete ‘right libertarianism’ that has come to dominate political conversations in the US and elsewhere.

Whether left or right, libertarians are primarily concerned with enabling the freedoms of individuals and our voluntary collaborations, and protecting them from the influence or intrusion by external and hierarchical powers, unless that is knowingly and voluntarily consented to by the people affected. All strands of libertarian thought regard personal freedoms as being our original state, whether that is understood as God-given or natural. Ecolibertarianism is a departure from right libertarianism, because it is not blind to the influence and intrusion of corporations—and the money-power of capitalism more generally—into our lives. Rather, it holds that freedom from such influence and intrusion must be central to us all recovering our liberty. Right libertarianism can be understood to have downplayed such threats to freedom precisely because of the power of corporations and capital in both culture and politics. That power has meant that many people assume that freedom is individualistic, rather than always being experienced collaboratively. It also has led to a denigration of attention to whether some rights are being mistakenly upheld at scale, with the key example being the freedoms of corporations to escape accountability to those they affect.

That limitation in their political agenda is not because of an absence of right libertarian thinkers who encouraged us to curb corporate power in the interest of everyone’s freedom. For instance, both Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman were keen on antitrust laws to prevent monopoly practices. Murray Rothbard went far further to argue that corporations should not exist in their current form, where they have protections such as legal liability and unusual advantages in financing and tax—features he argued are a product of their influence over government.

On environmental issues, the mainstream right libertarianism of the US has mainly focused on making the argument that spreading property rights and trusting human ingenuity is the way to respond. As chronicled in my book, that has been an influential idea that has not got us far with protecting the environment. Although one family owning their property might mean that they take better care of it and consider long term environmental issues, transferring that idea to the global scene where billion-dollar corporations shape policies to maximize profit is a rather cavalier intellectual mistake. It is a mistake that serves elite interests. Instead, by recognising the abuse of corporate power as a feature, not side effect, of our economic system, ecolibertarianism breaks with the popular but failed market fundamentalism of some right libertarian thinkers on the environment. Instead, it is resonant with the existing range of left libertarian thought, which all support alternative economic systems that prioritise forms of worker and community control, such as worker and consumer cooperatives. One of the key thinkers in this field was the American writer Murray Bookchin, who emphasised the decentralisation of power as a pathway to ecological sustainability and social justice.

However, we need to look beyond the West to see where such ideas gained real influence. Lala Lajpat Rai was an Indian philosopher who was influential in the Indian independence movement in the early 20th century. He viewed natural resources like forests, rivers and mineral reserves, as communal property that should be collectively managed. Although he and Mohandas Gandhi disagreed on some of the methods for achieving independence for India, they shared a vision of a communally governed economics that would respect nature. Perhaps the most important figure in guiding India into independence, the economist Babasaheb Ambedkar, also shared such views on the importance of more common ownership of key resources. The ongoing power of producer and consumer cooperatives in India today is reflective of this tradition.

The global history and experience with left libertarianism is important to recall at this time, as we urgently need a bold politics of solidarity for this difficult age of societal disruption. The left can’t keep pretending that heaven-on-Earth awaits if only the electorate finally choses a properly socialist government. That was my main message during an interview with the leftwing media outlet Novara. I also warned of the need to offer an alternative to growing authoritarianism from the left, right and centre of politics. This is also appearing within the environmental movement. As environmentalists become ever more desperate at the state of the world, some are advocating for more draconian controls from the state and big tech. Ecolibertarianism offers an empowering alternative to such authoritarian nightmares. That is why many people with extensive experience on green issues are resonating with the ideas, including Green Party politicians like Indra Donfrancesco, leading climate activists like Gail Bradbrook, and community development catalysts like Low Impact. The big question is whether they will be joined by the many thousands of professionals who truly care about the plight of people and planet but have ended up in counterproductive day jobs that tolerate, or serve, the destructive and delusional systems of modern societies.

If the professional classes finally accept that their lives will not improve, and ditch their deference to incumbent power, where might a new era of ecolibertarian politics take us? Unfortunately, the ecological situation is dire. Therefore, I think it would be naïve and unscientific to claim we can reach a utopia of environmental sustainability. What we can aim towards is a situation where the majority of humanity awakens to the damage done due to the stories that delude us and the systems that damage us. From that awareness, people will find their own ways to reduce harm, restore nature and find meaning. Therefore, I speak of an ‘evotopia’. The prefix ‘evo’ means to behold or witness and ‘topia’ means a place or reality. Evotopia is the idealised scenario where humanity returns to beholding reality more fully, so that both destruction slows and beauty flows. I consider that a more realistic vision for our time. Let’s remember that young people must live through the future that is coming, not the one that adults prefer to imagine, to assuage our worry and guilt. That means young people might especially welcome a refreshed political philosophical framework that responds to our era of societal disruption and global exploitation. That need was well summarised by Dr Richard Hill, an Adjunct Professor at Griffith University in Australia:

“For growing numbers of young people, the tired modernist stories of certainty, growth and progress no longer hold. The idea of the good life is viewed with disdain. The ravaging of the earth by cannibal capitalists tells of a system of selfishness, moral betrayal and nihilism that utterly repels. Young people now have to face the world as it is, and the future as it is likely to unfold. As Jem Bendell points out in his latest book, ‘Breaking together: A freedom-loving response to collapse’, the old stories of wealth accumulation, endless expansion and extraction are terminally fractured, to be replaced, one hopes, with Indigenous-inspired narratives of reconnection and regeneration. Reaching out to others, building solidarities, relearning skills for survival and cooperation, sharing thoughts and feelings, being still and contemplative rather than dashing into action, all this and more will be needed as we confront the realities of climate nihilism.”

Young people around the world deserve a new kind of leadership that responds to the reality that Dr Hill summarised so well. It’s time that more of us stepped up to make it happen.

References to various points made in this essay are found in the book Breaking Together, which is available in all formats, including a free ebook download from jembendell.com. The image is a midjourney-generated watercolour of young people with the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia.

As far as I know, libertarianism means ‘Why wouldn’t I do what I want – fuck the others”.

Of course, wise people understand that we live in a society, and if I harm society I also harm myself, indirectly. But all people are not wise. There are always quite a lot that think that they gain by cheating. These are usually those who support libertarianism. Others favour some rules and some authority to keep the cheaters in check.