In this article, Chantal Mouffe, philosopher, professor at the University of Westminster and theoretician of left-wing populism, proffers an analysis of the strategy of Jeremy Corbyn, a strategy which seeks to transform the internal dynamics of the Labour Party and to revitalise British Social Democracy.

This article was translated and reprinted in The New Pretender from Le Vent Se Lève, with permission from the author and Le Vent Se Lève. Translation by Liam Farrell.

The crisis of European social democracy has now been confirmed. After the failures of PASOK in Greece, Partij van de Arbeid in the Netherlands, PSOE in Spain, the SPÖ in Austria, the SPD in Germany and the Partie Socialiste in France, the PD in Italy have just received the worst election results in its party’s history. The single exception to this disastrous vista across Europe is to be found in Great Britain, at the Labour Party, which under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn is rapidly growing in size and power. With more than 600.000 members, Labour is now the largest left-wing party in Europe.

But, how did Corbyn, much to the surprise of his own party, pull this off?

After an attempted leadership coup by the right-wing of the party in 2016, the decisive moment in the consolidation of Corbyn’s leadership came with the strong growth of the party at the polling booths in the June 2017 elections. Even though opinion polls gave a 20 point lead to the Conservative party, the Labour Party gained a significant 32 seats, depriving the Tories of their outright majority in parliament. The strategy put in place for this election is precisely what gave Corbyn his success.

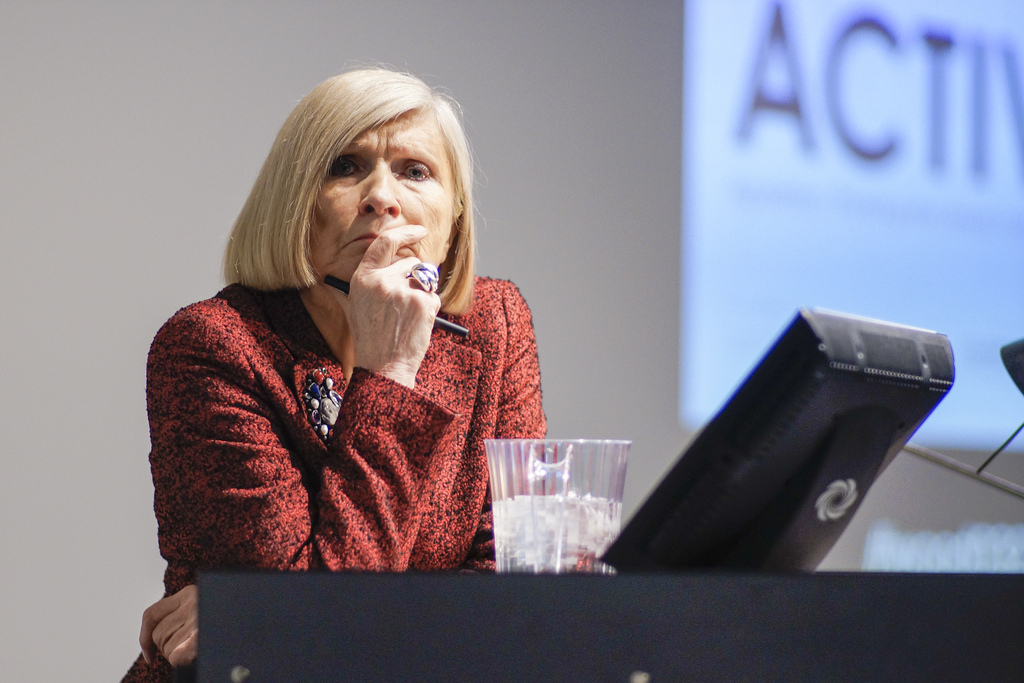

© Sophie J. Brown [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Such a success, and Corbyn’s breakthrough was down to two principal factors.

First of all, a radical manifesto, which captured the widespread rejection of austerity and the policies of neoliberalism by a very large portion of British society. Secondly, this was supplemented by the support and formidable mobilisation of activists by Momentum, the movement established in 2015 in order to campaign for Corbyn’s leadership candidacy.

Inspired by the movements of Bernie Sanders in the USA, as well as new radical groups across Europe, Momentum has seized the opportunities of digital resources and social media to create extensive communication networks that have enabled activists as well as many volunteers to come together, and to organise their focus when canvassing in marginal constituencies. It was through this unexpected mobilisation of members and activists that Corbyn managed to defy all of the predictions.

But, it was Corbyn’s radical manifesto which stood as the condition of possibility for all of this mobilisation. The manifesto’s title ‘For the Many, Not the Few”, re-articulated an old Labour slogan, giving it a new content, through the drawing of a new political frontier, between an “Us” and a “Them”. This involves the re-politicisation of public debate and the projection of an alternative to the neo-liberalism introduced by Margaret Thatcher, which was then followed and naturalised by Tony Blair.

“The objective is to establish a chain of equivalence between the different democratic struggles across British society and to transform the Labour Party into a large popular movement capable of articulating a new hegemony”

The central measures in the manifesto included the re-nationalisation of public services, especially the rail networks, energy providers, the postal service, and to bring to an end the privatisation of the national health service (NHS) as well as the education system, the abolition of student fees, and to increase spending on welfare. All of this signalled a significant rupture with the Third Way ideology of New Labour.

Whilst the Third Way had articulated the concept of “liberty” in terms of the market, and the ‘freedom to choose’, this new manifesto reaffirmed the Labour Party’s credentials as a party of equality. It’s other important point was its insistence on democratic control, as it gave emphasis to the very democratic character of all of the measures it proposed to establish a more equal social order.

State intervention was invoked by the manifesto, but this role for the state was conceived to be necessary in order to create the conditions that will empower citizens to take part in the management of public services. This insistence on the necessity to deepen and radicalise democracy is one of the key principles of Corbyn’s hegemonic project.

This deepening of democracy resonates particularly with the spirit of Momentum, which proposes and seeks to build links with the social movements. This explains the central place given to the struggle against all of the forms of domination and discrimination, from economic relations to other domains like feminist, anti-racist and LGBTQ+ struggles.

It is the articulation of these struggles alongside other forms of domination which stands at the heart if Corbyn’s strategy, and thus qualifies it as a “populism of the left”. The objective is to establish a chain of equivalence between different democratic struggles across British society and to transform the Labour Party into a large popular movement capable of articulating a new hegemony.

It is clear that the realisation of such a project would signify for Great Britain, a turn as radical as – though in the opposite direction to – that of Margaret Thatcher. Certainly, the struggle to redefine the Labour Party is not yet over, and the internal struggle by the left-wing over Blairism continues. As such, Corbyn’s opponents employ a multiplicity of manoeuvres to try and discredit him, the latest being an attempt to characterise the leadership and the left-wing of the party as tolerant of anti-semitism.

“Under Corbyn’s leadership, Labour has managed to restore the appeal of politics to those which has deserted it under Blair and to attract more and more young people”

Tensions also exist between those who support an older, more traditional account of “Labourism”, and those who advocate the “New Politics”. But, it is the latter group which are winning out. Corbyn’s advantage, which he enjoys unlike his comrades in Podemos or La France Insoumise, is that he finds himself at the head of a large party, which has overwhelming support from the unions.

Under Corbyn’s leadership, Labour has managed to restore the appeal of politics to those which has deserted it under Blair and to attract more and more young people. This proves that, contrary to what many political scientists claim, party politics has not yet become obsolete, and that by articulating itself alongside social movements, parties can be renewed. It was the move from social democracy to neoliberalism that was behind the disaffection of labour voters under Blairism.

When one offers to citizens an alternative vision, and they have the opportunity to participate in a properly agonistic debate, they will be quick to ensure their voices are heard. But this requires that we abandon technocratic conceptions of politics which reduces it to technical questions of economic management, and we recognise and prioritise its properly partisan character.

Be the first to comment