That climate change will increase the cost of living is unavoidable. Why is that not part of the discussion concerning the climate emergency?

Chloe Musto is Media and Campaing Officer at Positive Money

Cross-posted from Positive Money

Much of the commentary on climate change rightly asks whether our water will be drinkable, our air breathable, and our food edible on an increasingly polluted planet. But given soaring prices over the last year, there’s another question we need to answer first: will the things we need to survive be affordable in the years to come?

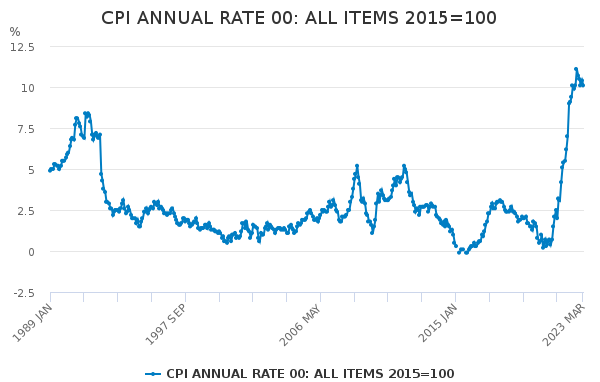

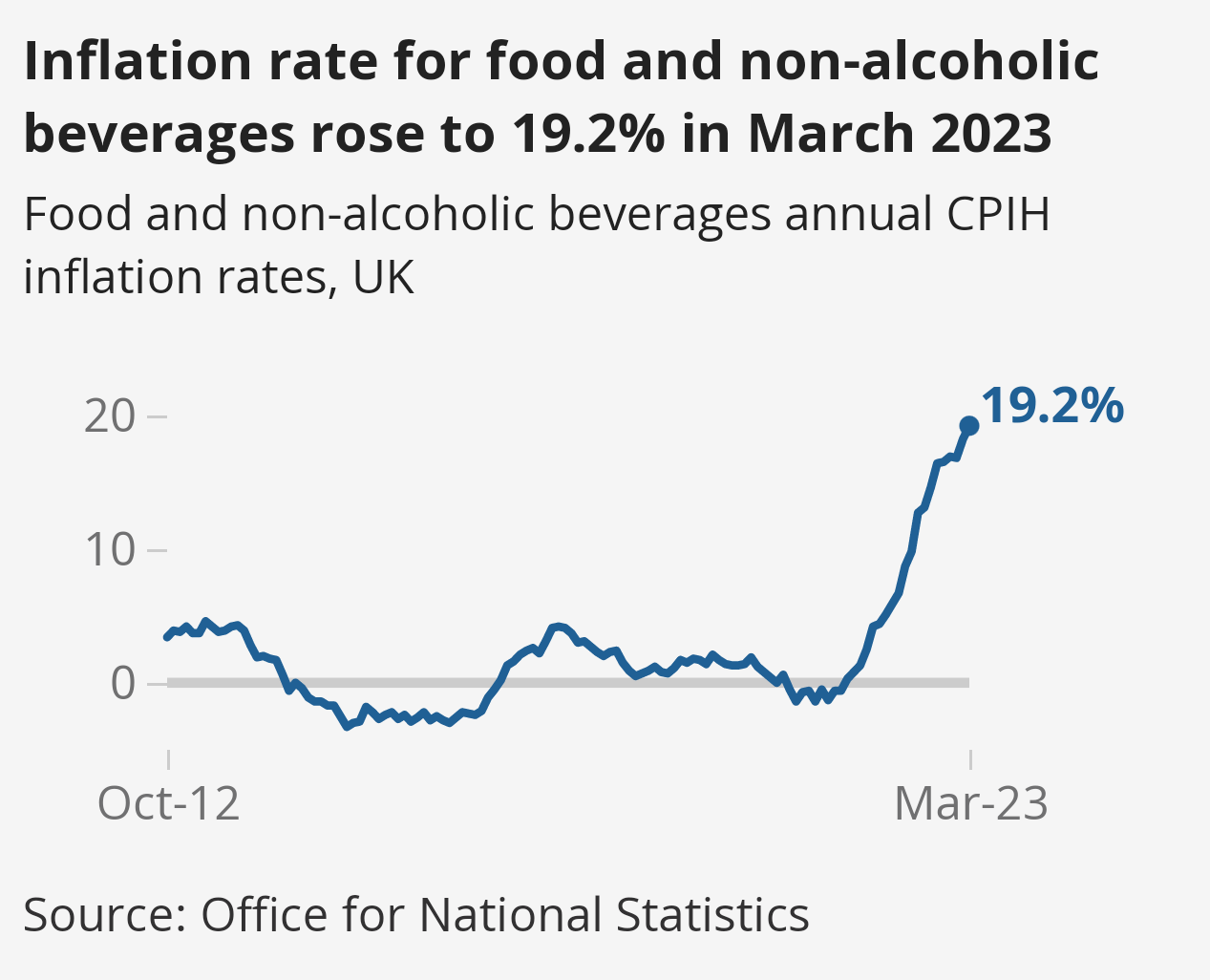

Today’s new inflation figures from the Office for National Statistics paint a bleak picture. Whilst they show that Consumer Price Inflation (CPI) fell to 10.1% in March from 10.4% in February, if we look at the inflation rate for food and non-alcoholic beverages, that figure rose from 18.2% in February to 19.1% in March – almost double the CPI rate, which looks at a mixture of goods across the economy. This is the highest food price inflation has been in 45 years.

Source: Office for National Statistics

Last week we talked about the effects of fossilflation: how the volatility of fossil fuel prices on international markets leaves us vulnerable to price shocks for as long as we depend on them. Fossilflation can likewise explain part of the picture when it comes to rising food costs, because farmers have struggled to heat and light greenhouses due to the rising cost of energy.

However, the greater driver of rising food prices is a separate (albeit related) phenomenon called climateflation. This term describes the way that fossil-fuel-driven global warming causes more frequent and severe extreme weather events, which then disrupt production of basic goods we all rely on, sending their prices soaring.

The examples are plentiful: droughts devastating Italian rice crops, Argentinian soybean yields, Spanish olive oil production, and American corn and wheat. New research even points to a surge in plant pandemics caused by rising temperatures. But it’s not just droughts doing the damage, wildfires and heavy rains threaten vineyards, unseasonal hailstorms have destroyed wheat in India (the world’s second-largest producer of the crop), whilst frosts have killed American apples and Brazilian coffee. Even meat availability has been impacted, with farmers unable to produce feed for their livestock.

The blow to prices has been felt worldwide. Spain’s status as the world’s largest olive-grower means poor crop yields there could’ve pushed the price of olive oil up by as much as 25%, and because Brazil is the world’s largest coffee-producing country, their inability to produce pushed the price of coffee up 70% between April 2020 and December 2021.

On our current trajectory, the predictions are bleak: from nations not being able to produce the crops that have fed them for millenia, to certain food species dying out altogether. Research published last year put the cost of losses from climate change to food and farm investors at $150 billion by 2030 if they fail to adapt to changes in government policy and consumer behaviour.

Food shortages in Britain have been largely attributed to unseasonal cold spells earlier this year reducing crop yields in southern Spain and north Africa. Some commentators would seek to blame our exit from the European Union for food shortages, and whilst this has undoubtedly worsened our situation, the truth is our chosen replacement countries have been subject to the same crop failures as those within the EU. Even Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey acknowledged that “the rise in food prices is a global phenomenon, exacerbated by adverse climate conditions.”

Beyond our own financial struggles, we must also consider the unequal distribution of the effects of climateflation. Recent research from the University of Edinburgh found that of the one million additional deaths further food price rises could cause, “the greatest increases in deaths would be in Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa and the Middle East.” We need look no further than the unprecedented famine unfolding across Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia to see this already playing out.

Blows to labour productivity caused by heat stress on workers in an ever-warming world will likewise be felt most acutely in the Global South. The International Labour Organisation estimates $2.4 trillion of global financial losses will arise from heat stress on workers by 2030. The Global North won’t remain untouched by heat stress on workers, however, with Californians already calling for greater heat standard protections for indoor workers due to their rapidly warming weather. Think tank Autonomy similarly predicts that extreme heat waves could put almost 28 million UK workers at risk from dangerous temperatures by 2050. The effects of this were already visible last summer, when extreme heat on wards caused a fifth of UK hospitals to cancel operations.

Then there’s the infrastructural damage caused by extreme weather to consider: global climate disasters cost at least £200 billion in 2022. Flooding, droughts and landslides have uprooted homes and livelihoods everywhere, from Germany to Pakistan to Nigeria. Whilst the US bore the greatest costs, spending more than $165 billion on 18 separate multi-billion dollar disasters in 2022, it could easily be argued that this is because the US has the world’s largest GDP; there are plenty of nations with equally devastating catastrophes that just have fewer funds to throw at the problem.

That was a lot to take in, and if you’ve made it this far you deserve a generous helping of positivity. Although the costs from climate change are great, the savings we stand to make by acting now sit in the trillions. The global transition to renewables could also pay for itself in as few as six years, and the savings that nations in the EU and Asia have already made by switching to renewables stood in the tens of billions last year.

To truly tackle climateflation, we need to target the international financiers funding the fossil fuel projects which are accelerating climate breakdown. If banks continue pouring billions into fuels that we’re going to be forced to abandon, they could trigger another financial crisis, and this time, global governments will be looking at a tab of $4.9 trillion of public money to bail them out as early as 2030.

In order for us to neutralise the threat banks’ investment behaviour poses, and mobilise finance towards the things we need, we must look to those with the power to redirect public and private finance. In the UK’s case, this means getting the UK government and Bank of England working together to steer us away from climateflation-causing fossil fuels and chart a new course towards renewables and retrofits.

Thanks to many generous donors BRAVE NEW EUROPE will be able to continue its work for the rest of 2023 in a reduced form. What we need is a long term solution. So please consider making a monthly recurring donation. It need not be a vast amount as it accumulates in the course of the year. To donate please go HERE.

Be the first to comment