Where there is monopoly, or the opportunity for egregious exploitation, or agency failure, then the case for free markets diminishes.

Chris Dillow is an economics writer at Investors Chronicle. He blogs at Stumbling and Mumbling, and is the author of New Labour and the End of Politics.

Cross-posted from Chris’s website

There’s a paradox: Liz Truss’s government contains many members who claim to be free marketeers, and yet the first policy of her premiership has been to freeze energy prices and subsidize energy suppliers.

This poses the question: what does it mean to be a free marketeer today? One way to consider this is to ask what’s so good about markets anyway, and whether these values can be strengthened (or even salvaged) in today’s economy.

First, though, let’s remember what are not arguments for free markets.

It is not the case that they yield “optimal” outcomes. Yes, they do so in theory, but only under conditions which have never actually existed.

Nor is it the case that free markets are “natural” and government “interventions” therein artificial. As Jesse Norman wrote in his excellent Adam Smith: what he thought and why it matters: “It makes no sense to speak of humans in a state of nature prior to society, because humans are social by nature.” And in Free to Choose (pdf), Milton Friedman said: “There is nothing ‘natural’ about where my property rights end and yours begin.” Sensible defenders of a market economy have always acknowledged that it rests upon the foundation of a well-functioning state.

Still less is it the case that markets deliver economic stability. Perhaps the nearest we have come to a free market was in 19th century England and the US. But both saw frequent recessions: 15 in the US between 1857 and 1914 according to the NBER, whilst the UK saw 13 calendar years of falling real GDP between 1846 and 1914. Still less do markets deliver social stability: an essential feature of them is the creative destruction that wipes out the industries on which some communities depend.

If these are not the virtues of markets, what are?

Let’s start at the beginning, with Adam Smith. His phrase, “the invisible hand” appears only once in the Wealth of Nations as an almost throwaway remark. Instead he, like his kindred spirit Edmund Burke, devoted far more time to excoriating monopoly – the East India Company. It, he said, not just “oppresses and domineers” Indians but also impoverishes the English:

Since the establishment of the English East India Company, for example, the other inhabitants of England, over and above being excluded from the trade, must have paid in the price of the East India goods which they have consumed, not only for all the extraordinary profits which the company may have made upon those goods in consequence of their monopoly, but for all the extraordinary waste which the fraud and abuse, inseparable from the management of the affairs of so great a company, must necessarily have occasioned.

For Smith, the antithesis of the free market was not big government but monopoly and privilege. And well-functioning free markets attack privilege by allowing new companies to compete away the profits of erstwhile monopolies. They are an egalitarian device. Every billionaire is a market failure. As Jesse Norman wrote:

High profits over any sustained period are a sign for Smith of poorly functioning markets…They’re associated with poorer, not richer, societies; and with failure not success.

Free marketeers in the Burke and Smith tradition cannot defend water companies which, like the EIC, are pure monopolies. Nor can they be happy with sustained profits of any business, insofar as these might well be signs of barriers to entry and inadequate competition.

Smith saw another virtue in well-functioning markets. For him – as Norman stresses – markets both require and cultivate sympathy. If you want to thrive in a competitive market you must put yourselves in the shoes of the customer by asking: what does he want? This simple act leads to a fellow-feeling in a way that relations of domination and subjection do not. And repeating the act leads naturally to an extension of that fellow-feeling into other domains. Which is why Montesquieu thought that commerce “polishes and softens barbaric ways.” Richard Cobden, for example, was not just an anti-Corn Law campaigner but also a pacifist.

One manifestation if this today is “woke capitalism”: in an effort to shift product, some companies profess to support liberal causes. Granted, such claims can be hypocritical – hypocrisy is the tribute vice pays to virtue – but no free marketeer in the Montesquieu tradition can object to them.

The opposite of a great truth, though, is another great truth. G.A. Cohen has said that markets lead us to view others as either threats or potential sources of enrichment which are, he wrote, “horrible ways of seeing other people.” This is more likely to be true when markets don’t function well. Water companies pouring shit into the sea; Royal Mail bosses taking big bonuses whilst demanding that workers take pay cuts; and scammers looking for new marks validate Cohen’s view more than Smith’s.

Another virtue of free markets – stressed by Friedman and Hayek – is that economic freedom is associated political freedom. As Friedman put it:

A predominantly voluntary exchange economy…has within it the potential to promote both prosperity and human freedom. It may not achieve its potential in either respect, but we know of no society that has ever achieved prosperity and freedom unless voluntary exchange has been its dominant principle of organization (Free to Choose, p11)

Smithian sympathy is one mechanism here. If our economic transactions lead us towards a fellow-feeling for others, we’ll be more likely to want him to have political freedom. And if we are free to choose our butcher or coal merchant, we will want to be free to express our political or religious opinions.

This argument for freedom, however, runs into the obvious Marxian objection. Whereas markets are, he said “a very Eden of the innate rights of man”, they lead to the exploitation, domination and unfreedom of the worker, who “is bringing his own hide to market and has nothing to expect but – a hiding.” The free marketeer who values real freedom will thus support measures which prevent workers being forced into egregiously degrading work – such as policies to promote full employment or a basic income.

Well-functioning free markets don’t just foster equality, freedom and civility, though. They can also enhance economic efficiency.

One way they do so was stressed by Hayek. A great virtue of markets is that they aggregate dispersed, fragmentary and fleeting information into one simple fact – a price – and so facilitate better, quicker decision-making:

We need decentralization because only thus can we insure that the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place will be promptly used…in a system in which the knowledge of the relevant facts is dispersed among many people, prices can act to coördinate the separate actions of different people.

Of course, this doesn’t always work effectively. In asset markets especially agents can misinterpret prices thereby “chasing noise” and creating bubbles. But for free marketeers following Hayek, it is an advantage over state direction.

There are, however, some corollaries of this from which some free marketeers resile.

One is that a lot of private sector economic activity consists in overlooking dispersed localized information. Large companies are centrally planned economies in which workers’ knowledge is ignored or effaced: Harry Braverman’s beef with scientific management was that it destroyed craft knowledge. There’s a Hayekian case for worker democracy (pdf).

Another is that oligarchic mass media might have a pernicious influence. Insofar as it gives excessive weight to a few very similar points of view it over-rides localized dispersed knowledge and causes ideas to become more correlated across people. That weakens the conditions necessary for there to be wisdom in crowds.

A further way in which markets facilitate efficiency is by sharpening incentives. Friedman said that when you spend your own money on yourself “then you really watch out what you’re doing, and you try to get the most for your money.” By contrast:

If I spend somebody else’s money on somebody else, I’m not concerned about how much it is, and I’m not concerned about what I get. And that’s government.

It’s for this reason that free marketeers should be queasy about the government’s plan to cap energy prices. Yes, there’s a case for intervention: gas prices are high largely because of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, which is not market activity. But the cap means that rather than spending our own money on our energy, the government is spending other people’s money on it. That weakens incentives to curb energy use. Sunak’s policy of letting prices rise but giving lump sums to every household was, from this perspective, closer to a free market solution.

But, but, but. Not all private sector economic activity consists of us spending our own money on ourselves. Fund managers spend somebody else’s money on somebody else – which is why hedge funds thrive despite poor returns. Likewise, the investment decisions of large companies mean people spending other people’s money, with often lacklustre results.

The point here is that not all private sector economic activity delivers the goods of liberty, equality or efficiency. Where there is monopoly, or the opportunity for egregious exploitation, or agency failure, then the case for free markets diminishes. You can therefore be a free marketeer whilst opposing private sector monopolies such as the utilities, favouring financial regulation or supporting institutions such as trades unions. Markets best facilitate the virtues claimed for them when they operate within the right cultural and institutional framework. As Jesse Norman wrote:

Markets are sustained not merely by incentives of gain or loss but by laws, institutions, norms and identities.

Economies performed much better – in terms of faster and more equitable growth – in the post-war period than they have since the 1980s, not least because norms and institutions (one of which was strong trades unions) facilitated that.

As Edmund Burke said:

Circumstances (which with some gentlemen pass for nothing) give in reality to every political principle its distinguishing colour, and discriminating effect. The circumstances are what render every civil and political scheme beneficial or noxious to mankind.

From this perspective, free marketeers must be saddened by rising energy prices just as they bewail increased state spending – because both mean that the proportion of economic activity devoted to beneficial market activity is shrinking.

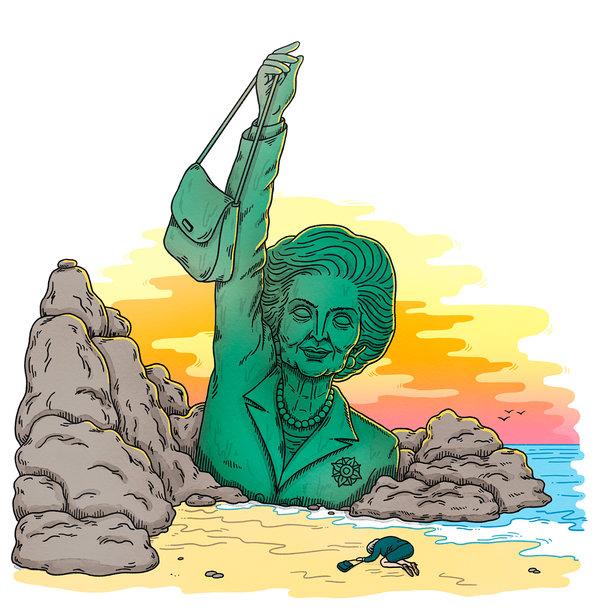

By now, some of you will think I’m being horribly naive. “Free marketeers”, you might say, are not those who believe that some markets, in some conditions, promote virtues. Instead, they are just shills for monopolists and rent-seekers. You’d be right. Just as the left should reclaim the cause of freedom from the right so too should it reclaim the cause of free markets. To the faux free marketeers on the right we should paraphrase the Muslim speaking to the terrorist: “You ain’t no free marketeer, bruv”.

Support us and become part of a media that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over.

Be the first to comment