We pay our taxes, so why don’t corporations? This new report shows how the Big Four are embedded in EU policy-making on tax avoidance, and concludes that it is time to kick this industry out of EU anti-tax avoidance policy.

Cross-posted from Corporate Europe Observatory

Billions of euros are lost each year due to corporate tax avoidance, depriving public budgets of much-needed funding. The EU plays an increasing role in the creation of tax-avoidance related rules following numerous scandals, many of which have highlighted the role of tax advisers in designing and selling tax avoidance schemes to multinational corporations. The Big Four accountancy firms – Deloitte, EY, KPMG, and PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC) – are the goliaths of the tax planning world. Given their role as key players in the tax avoidance industry it is remarkable that the EU and its member state governments consider them legitimate and neutral advisers in policy-making. They are omnipresent in the EU’s policy processes to tackle corporate tax avoidance (despite their vested interest) and work through several channels of influence:

Public procurement contracts: The Big Four receive tens of millions from the European Commission in public procurement contracts each year. The Commission’s tax directorate paid PWC, Deloitte, and EY €7 million in 2014 to carry out studies and analyses in “various tax and customs areas”. This means the enablers of major tax avoidance are paid for studies that inform the making of tax-avoidance related laws. Even after the LuxLeaks scandal revealed the role of the Big Four in facilitating corporate tax avoidance, nothing changed. In January 2018 PWC, Deloitte, and KPMG were awarded €10.5 million for studies on “taxation and customs issues”, with no regard to conflicts of interest. The Commission also hires tax advisers to give input on the very tax measures they lobby against. For example Deloitte was hired to conduct studies on transfer pricing – a method multinationals use to avoid tax – despite the fact that Deloitte advises corporate clients on transfer pricing, and had lobbied against stricter measures to tackle it.

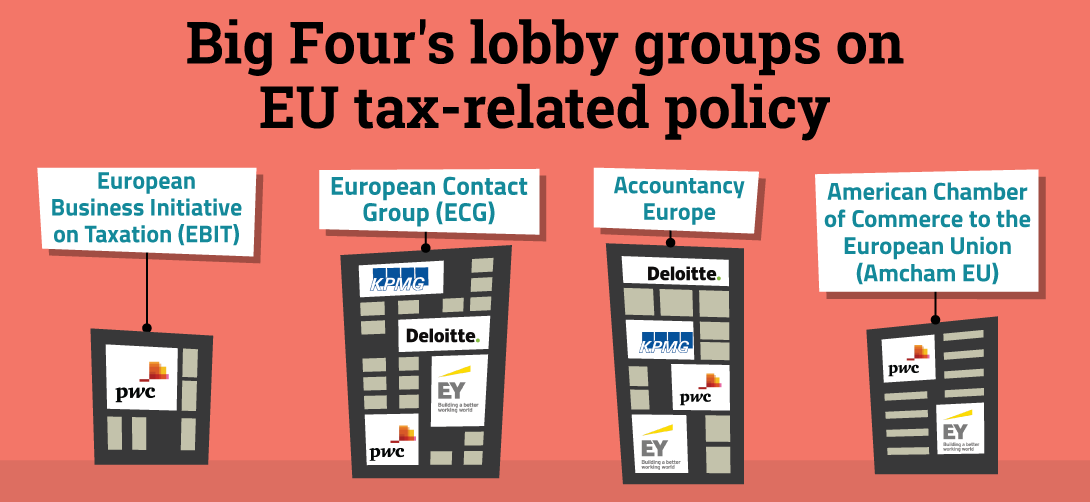

Lobbying associations: The Big Four have driving seats in various lobby associations trying to influence EU policy responses to tax avoidance.

- The European Business Initiative on Taxation – with members like BP, Pfizer, and Airbus – is run by PWC.

- The European Contact Group is an ‘informal’ grouping of the Big Four (and the next two largest accountancy firms), originally set up at the Commission’s request. Its goal is “shaping the regulatory environment”, with a successful history of doing so.

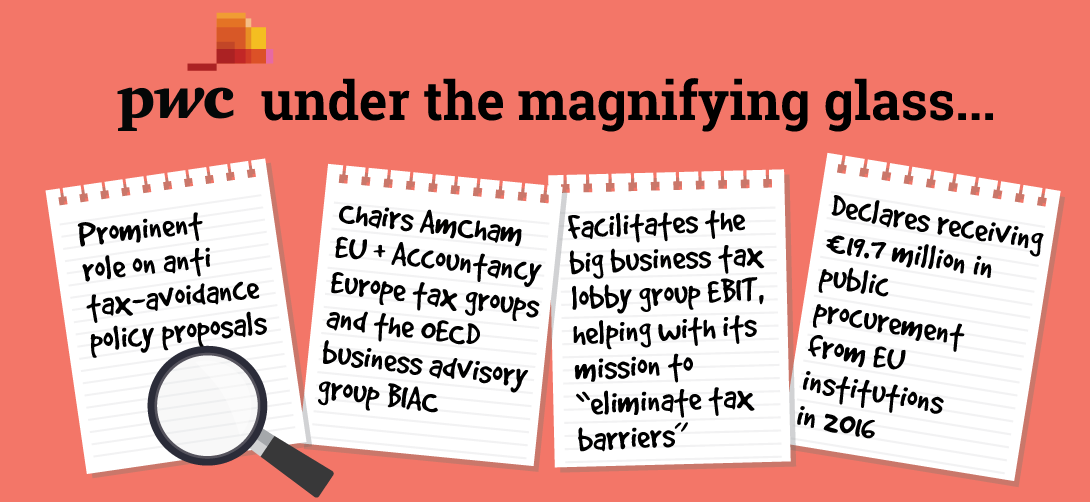

- Accountancy Europe is the accountancy profession’s federation, a regular and trusted voice in the Brussels tax policy sphere, with a board packed with Big Four figures. PWC chairs its tax policy group.

- The American Chamber of Commerce to the EU (AmCham EU) is a lobby association for US multinationals like ExxonMobil, Facebook, and Monsanto, and vociferous opponent of greater tax transparency; its tax committee is also chaired by PWC.

Advisory groups: The Commission’s advisory groups have a history of the tax avoidance industry being invited to give advice on how to stop tax avoidance. For example the Joint Transfer Pricing Forum has been dominated by large accountancy firms and financial institutions, and a mandate that prioritises the reduction of the burden on business over the prevention of transfer pricing to avoid tax. Despite tiny improvements, facilitators of tax avoidance still sit on the group, including Deloitte and PWC. The Platform for Tax Good Governance, set up to help implement EU plans to tackle tax avoidance, has also drawn flack for being dominated by corporate tax avoiders and their advisers. Small advances aside, the fundamental problem persists. While none of the Big Four sit in the group under their own names, PWC represents AmCham EU and Accountancy Europe.

Revolving door: The shared culture and assumptions between the Big Four and EU public officials working on tax-related policy are perpetuated by a normalised revolving door between the two. Most recently the former Finance Commissioner Jonathan Hill has become a senior adviser to Deloitte. Further examples are plentiful, from policy officers in the Commission’s tax directorate coming from Deloitte and EY; to its director of tax policy becoming a tax manager at Deloitte; to policy officers in the finance directorate sourced from KPMG and Deloitte. Meanwhile the tax or finance attachés for Ireland, Finland, Malta, and Germany come from PWC, Deloitte, EY, and KPMG respectively. Young professionals routinely hop between internships in the European Parliament or Commission and the Big Four, which helps breed a shared set of values. Decision-makers do not recognise that this constant staff-swap between firms that sell tax-avoidance, and the institutions responsible for tackling it, might breed conflicts of interest, and weaken the impetus for public interest regulation.

Case File 1: In June 2017 the Commission issued a proposal for new transparency rules for tax advisers which required them to report to financial authorities ‘aggressive’ tax schemes (which help clients avoid tax) that they design or sell. KPMG and PWC had pushed for a voluntary approach instead. When this failed, lobbying efforts shifted focus to the Council, where the eventual agreement diluted the proposal in ways that bore a strong resemblance to PWC’s advice. PWC had set out detailed arguments for member states to use in support of amendments, including that the proposal as it stood would “disproportionately burden” interests such as the Big Four and its corporate clients. PWC also suggested narrowing the criteria for what counts as ‘aggressive’ (so fewer schemes would be reported), and requiring a unanimous vote to add or change these criteria, making it easier for newly cooked-up tax avoidance schemes to remain unreported. The Council’s final text, agreed in March 2018, had been weakened in all of these ways. Lack of Council transparency means we cannot know exactly how influential PWC or the wider tax avoidance industry was, but there are known close links between some member state governments and the Big Four.

Case File 2: The Big Four, and the multinationals they advise, have lobbied hard against public country-by-country reporting. This would require corporations to publicly report their profits in every country they operate in, to avoid them exploiting loopholes to shift profits to tax havens. Ahead of the Commission’s proposal of April 2016, the Big Four lobbied fiercely against the requirement that this information be made public, EY citing “commercially sensitive information” and Deloitte pushing a ‘voluntary’ approach. Many big business lobbies repeated similar messages. The timely release of the Panama Papers however meant the Commission’s final proposal was stronger than expected. Efforts then moved to the European Parliament where, after a barrage of corporate lobbying, a get-out clause that allows corporations to keep “commercially sensitive” data secret was added by MEPs. Some of the most vehement efforts to undermine public reporting came from members of the Platform for Tax Good Governance: AmCham EU, BusinessEurope, German business lobby BDI, and its French counterpart MEDEF. AmCham EU, which argued that public reporting would harm competitiveness and Europe’s “attractiveness” for investment, has PWC in the driving seat on tax policy, as does Accountancy Europe. The latter was supportive of public reporting only if done in a way that minimised “the risk of disclosing economically sensitive information”; arguably, the get-out clause achieved this aim.

| Kick the Big Four out of tax avoidance policy

Despite all the evidence – from tax scandals to parliamentary enquiries – of the role the Big Four play as intermediaries that facilitate and profit from corporate tax avoidance, they continue to be treated in policy-making circles as objective and legitimate partners. It is time to kick the Big Four and other players in the tax avoidance industry out of EU anti-tax avoidance policy. This must start with recognition of the conflict of interest in allowing tax intermediaries to advise on tackling tax avoidance. Only then can an effective framework emerge which ensures public-interest tax policy-making is protected from vested interests. |

Published by Corporate Europe Observatory, with support from:

EPSU – European Federation of Public Service Unions www.epsu.org

AK Europa – Brussels office of the Austrian Federal Chamber of Labour (BAK) www.akeuropa.eu

ÖGB Europabüro – Brussels office of the Austrian Trade Union Federation (ÖGB) http://www.oegb-eu.at

https://corporateeurope.org/BigFourTax

Be the first to comment