Why is the EU still building new and unnecessary gas pipelines and LNG terminals?

Who’s pushing them and who’s profiting from them?

The companies behind Europe’s gas transport network are rarely household names, yet their lobbyists sit at the heart of our political system. They make their money building and operating pipelines and other gas infrastructure projects, and are desperate to keep us hooked on fossil gas, despite the climate science and widespread local opposition.

Corporate Europe Observatory is a research and campaign group working to expose and challenge the privileged access and influence enjoyed by corporations and their lobby groups in EU policy making.

Cross-posted from Corporate Europe Observatory

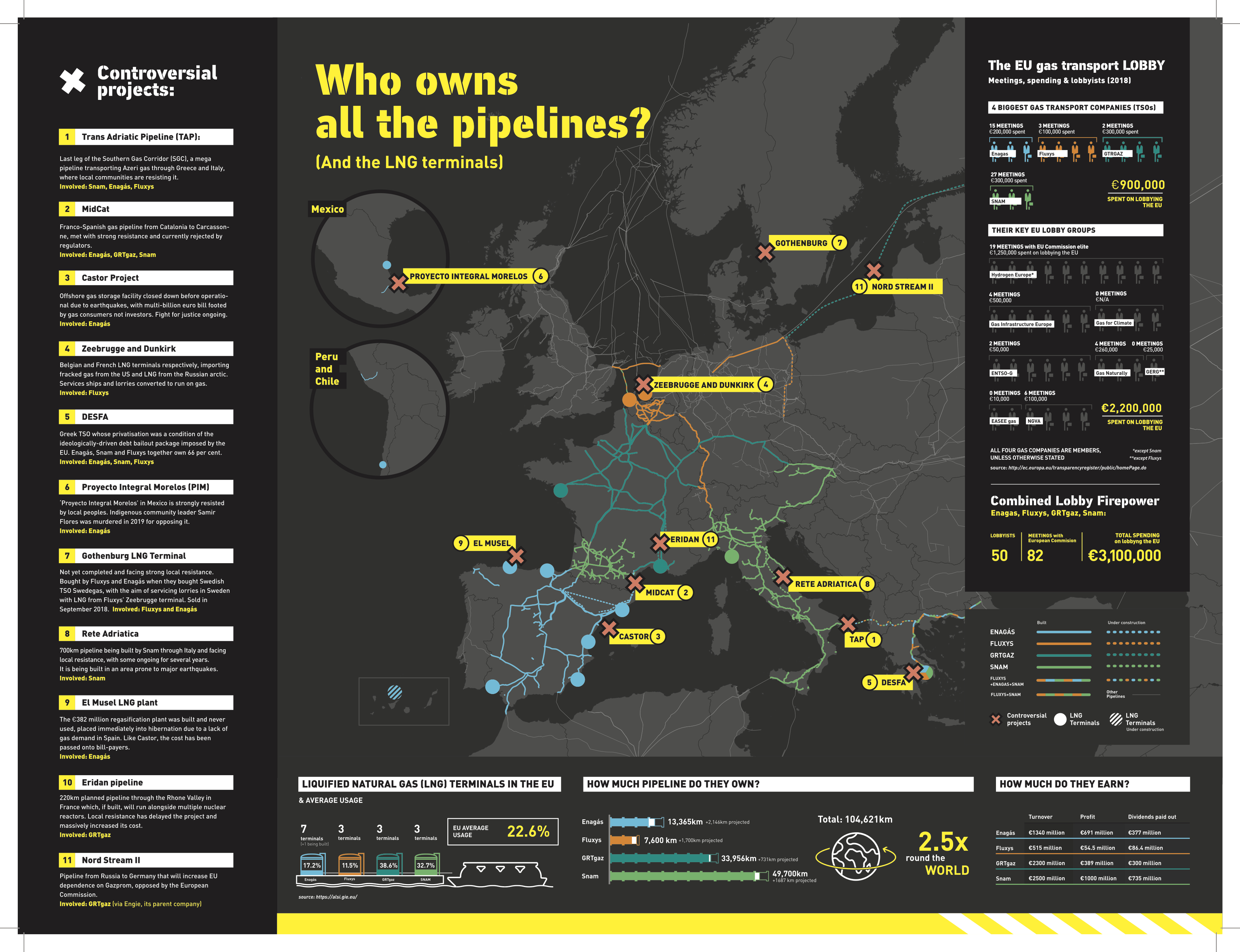

We take a look at four of Europe’s biggest: Enagás (Spain), Fluxys (Belgium), GRTgaz (France), Snam (Italy) and try and answer some key questions:

- How much infrastructure do they own and who are their subsidiaries?

- Who are their CEOs and who’s on their board?

- How much profit do they make and who are the shareholders filling their pockets?

- What is their lobbying power and who do they pay to do it?

These are important questions as together these little-known gas “transmission system operators” (TSOs) own enough kilometres of pipeline to stretch around the world two and a half times, with plans for more, including controversial projects like the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP). They are going to be key players in deciding if and how we tackle the climate emergency, as well as who pays for it. They’re not to be ignored.

Our two-sided map, available as a PDF and in print-version, visualises not only their pipelines and terminals, but also answers many of these questions graphically. It also includes four company profiles and four case studies of some of their controversial projects.

However, this article goes beyond the company profiles and case studies (which can still be found at the end of the page), providing extra information and analysis not available on the map, digging further into who owns the four TSOs, the consequence of having financial investment funds as investors (what does it mean for leaving fossil fuels in the ground and the just transition?), as well as more information on their lobbying activities.

If you want a compact and beautifully designed pdf version of the map, complete with company profiles and case studies, we have it available in English, French, Spanish, Italian and Flemish Dutch.

The map and this article are part of a cross-border research project by the European Network of Corporate Observatories (ENCO) on behalf of Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO), Re:Common, Observatori del deute en la globalització (ODG), Observatoire des Multinationales and Gresea.

If you want to print the two-sided map/profiles in full-size to fold and distribute, you will need to take both of these files to a print shop: English (side A, side B), French (side A, side B), Spanish (side A, side B), Italian (side A, side B), Flemish Dutch (side A, side B)

The biggest gas companies you’ve never heard of

Enagás (Spain), Fluxys (Belgium), GRTgaz (France) and Snam (Italy) are Europe’s four biggest gas transporters (TSOs), owning infrastructure across the continent and beyond. Together they own more than half of the EU’s LNG terminals and over 100,000km of pipeline, with new projects planned: 6,200km of pipeline and at least one more LNG terminal are under construction.

All four are run like private companies, despite being publicly-controlled (see more below). They collectively made more than €2 billion in profit in 2018 with almost three quarters paid out in dividends to shareholders such as investment funds BlackRock (GRTgaz and Snam) and Lazard (Enagás and Snam).

In-house and for-hire gas lobbyists

These little-known companies don’t have the profile of Shell, Total or BP, but are just as influential in keeping Europe dependent on gas. The four spent up to €900,000 on lobbying Brussels last year, employing a total of 14 lobbyists. According to the EU’s transparency register, they’ve managed to secure almost 50 meetings with the European Commission’s top political officials to discuss their latest pipeline projects or takeover bids.

As well as their own in-house lobbying operations, the four have invested in a broad network of paid-for lobby groups to push their agenda. This includes their industry trade association Gas Infrastructure Europe (GIE), which sits on a number of the Commission’s influential advisory groups. Handily, SNAM’s CEO Marco Alverà is well-placed to ensure all group are on message. He is currently the President of Brussels-based super-trade association, GasNaturally, which counts GIE as a member, and was previously Vice-President of Eurogas, another GasNaturally member.

Add the figures from Enagás, Fluxys, GRTgaz and Snam with those of their eight key lobby groups, and you hit above €3 million in 2018, with 50 lobbyists at their disposal. Not to be sniffed at when it comes to influencing European gas policy. However, their most important lobbying channel has been created by the EU itself.

Industry calls the shots on EU gas plans

The EU created its own in-house lobby group made up of gas TSOs, called the ‘European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas’, or ENTSO-G. It counts Enagás, Fluxys, GRTgaz and Snam as members. Despite being composed exclusively of gas companies, the EU tasked the group with providing projections of future gas demand in Europe, which it consistently over-estimates. The EU then asks ENTSO-G to provide it with a list of infrastructure projects to meet the projected demand. After being agreed by governments, this becomes the official list of ‘Projects of Common Interest’ (PCIs), which ENTSO-G members then build with financial and political support from the EU.

€1.3 billion in public money has already gone to projects such as MidCat, the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) and Fluxys’ LNG terminals. The fourth PCI list will be finalised by the end of 2019, with more than a hundred new gas projects currently included, despite the need to phase out fossil gas completely.

Gas – a false solution

Fossil gas spells disaster for communities and their environments, impacting them wherever it is drilled for or transported. It is also a disaster for the climate. So-called ‘natural’ gas is composed of methane, which is over 100 times more potent than CO2 over a ten-year period. Large quantities of gas leak into the atmosphere during drilling and transportation (particularly when fracking), making gas as bad for the climate as coal, if not worse.

Public companies captured by corporate interests

All of these companies originate in former state-owned national monopolies and retain some level of public ownership. Enagás is only 5% owned by the Spanish state, but with a veto right. Snam’s majority shareholder is CDP Reti, which is controlled by an Italian public financial institution (with a subsidiary of a Chinese state company). Fluxys is owned 75% by Publigas, an inter-municipal holding company. And GRTgaz is 75% owned by energy giant Engie (itself still 24% state-owned) and 25% by a French public financial institution.

The proximity of these companies to national politicians and government bureaucrats is obvious when you look at their boards and leadership:

- Enagás, which has long been a haven for politicians of all stripes, now has a former conservative MEP as a boss, who is also the son of a former minister. Its Chairman of the board is a former socialist minister.

- The chair of Fluxys is the former Mayor of Ghent (until 2019).

- GRTgaz‘s boss is a former high-ranking civil servant that used to be in charge of regulating the gas sector. Revolving doors are in full swing at all levels.

Sadly, this strong public presence does not mean that the now largely private companies are run with the general interest in mind; on the contrary, it means that public shareholding bodies have been captured by private interests, that are all the more influential because of their political connections. When they need special authorisations and state support to suppress resistance to their controversial projects, such as TAP in Southern Italy (see case study), the government is there to help.

Just as it is ready to bail them out at the expense of the public when one of their pet projects fails spectacularly, as was the case with the Castor project in Spain for Enagás (see boxes on TAP and Castor).

Sharing the pie and making it bigger

GRTgaz is probably the one that is still closest to its former public service self, but this is about to change. The French government passed a law in 2019 that allows for a raft of privatisations, including up to 49,9% of GRTgaz. This was justified as a way to help it grow beyond its borders and become a “European champion”. GRTgaz, which already owns gas pipelines in Germany, attempted to unsuccessfully buy out DEFSA, the Greek gas TSO, in 2017 (it was eventually acquired by a consortium of Enagás, Snam and Fluxys). It is said to be in talks with Open Grid Europe, a TSO owned by Australian investment fund Macquarie, which also has gas infrastructure assets in Germany.

This is a process that we’ve seen before in many sectors, from telecommunications to postal services and trains. National public companies have been privatised, sometimes dismantled, merged with foreign counterparts, progressively turning into a handful of giant corporations that dominate the European market and are hugely influential in EU decision-making.

It’s not about competition but about sharing the pie, and coordinating their efforts in Brussels to make the pie grow even bigger, with evermore support to new gas infrastructure throughout the continent.

It should come as no surprise then to see these new gas giants joining forces in controversial projects such as the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) or MidCat (see case studies), or to buy out remaining national companies such as DEFSA. Our four European pipeline giants now have assets not only in Italy, Spain, France and Belgium, their countries of origin, but also in the UK, Germany, Greece, Austria, the Netherlands, Albania and Switzerland. Next, they set their sights on markets outside Europe. Enagás in particular is already present in Peru and Mexico.

The gas infrastructure binge bringing millions to financial markets

As the “big 4” of gas transport gorge on ever more pipelines and LNG terminals at the expense of the climate and communities, former politicians and corporate executives are not the only ones who reap the profits. Their other shareholders, apart from governments, are large institutional investors, always happy with this kind of risk-free, guaranteed profit kind of asset.

They can be Wall Street managers such as BlackRock (which has a significant stake in GRTgaz’ parent company Engie and in Snam), Lazard (Snam and Enagás) or Goldman Sachs (Enagás). They can be pension funds such as Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (Fluxys). Sometimes they can be sovereign wealth funds, such as Singapore’s GIC, which holds more than 30 per cent in Terega, a French subsidiary of Snam.

But they have one thing in common: they love companies to churn out dividends. In 2018, GRTgaz, Enagás, Snam and Fluxys collectively transferred three quarters of their €2bn in profits straight into the pockets of shareholders. Belgian Fluxys gave out even more than it had made in profits, distributing extra cash from freed-up reserves so dividends totalled 160% of profits.

Holding back the energy transition

The pressure on Europe’s biggest TSOs to maximise dividends can also pose problems when trying to transform our energy system in response to the climate emergency. Leaving fossil fuels like gas in the ground would seriously dent the companies’ profits and therefore shareholder dividends.

So instead of talking about how to manage the necessary decline of fossil fuel production, decommission infrastructure and ensure a just transition for workers, the big four TSOs are making new excuses to keep their infrastructure being used. They propose embryonic techno-fixes like so-called ‘renewable gas’ or betting on costly and experimental ‘carbon capture and storage’ (CCS) technology.

All four are aggressively lobbying to have us believe these false solutions will ‘decarbonize’ gas by 2050. In the long-term they claim it would allow industry to meet the EU’s climate targets, but more importantly, in the short- to medium-term, it keeps them in business as we keep using fossil gas waiting for miracles technology to save us. These dangerous distractions are even being used to justify building more publicly-funded fossil fuel infrastructure.

However, with no ‘decarbonized’ gas in sight, shareholder pressure means any new gas infrastructure built today will still be in use by 2050, but based on good ol’ fashioned fossil gas. Or will shareholders be compensated by the public?

Suing to protect ‘lost future profits’

Imagine we do decide to move away from gas, who’s going to pay for it? Shareholder pressure means companies are unlikely to bear the costs themselves. In Spain, Enagás has already passed on the multi-billion euro cost to bill-payers of prematurely closing an offshore gas storage facility (see the Castor case study).

Elsewhere, the Dutch government is being sued by Uniper (previously E.ON) for trying to phase out coal. The German energy company and its investors are claiming compensation under the dangerous ‘Energy Charter Treaty’ for lost future profits. Unfortunately this is not the only instance.

The growing role of investment funds in Europe’s gas transport companies, and their knack at protecting their investments, lays a roadblock in the path to a just transition beyond fossil fuels. It takes democratic control away from workers, communities and decision makers when it is needed most.

If we want these companies to be public in more than just in name, we need to reverse the trend of privatisation and democratise gas transport companies so that they are also ‘public’ in how they behave and who they are accountable to.

Company profiles & case studies

Company: ENAGÁS

Country: Spain

Name: Enagás

Main shareholders: SEPI (5%), Lazard Asset Management (5.07%), Oman Oil Company (5%), JP Morgan Securities (4.2%), Merrill Lynch (3.6%), Goldman Sachs (3.6%), 100+ other banks and corporations.

Sociedad Estatal de Participanciones Industriales (SEPI), is the Spanish treasury’s holding company that manages public corporations. SEPI has de facto control of Enagás as it is the only shareholder with a veto right over decisions taken by other shareholders.i

CEO: Marcelino Oreja Arburúa

Ex-Partido Popular MEP and son of former Minister of the Interior

Chairman: Antonio Llardén Carratalá

Former Socialist Party (PSOE) minister, former Chairman of SEDIGAS, an association comprising Spanish gas companies.

Other board members: mainly ex-ministers and politicians.

Subsidiaries: Spain, Europe, Latin America, North America.

Most are owned by the group’s two main subsidiaries: Enagás Transporte (gas transmission in Spain) and Enagás Internacional (operations outside of Spain).

Turnover: €1.34 billion in 2018 with €691 million in profit. It paid out €377 million in dividends that year.

Despite increasing profits, Enagás is indebted by more than €5 billion, partly due to loans taken out for the controversial and never-used gas storage facility, Castor.

Controversial projects: TAP, Proyecto Integral Morelos, MidCat, Castor.

As well as the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP – see case study), MidCat (see case study), and Castor (see case study), Enagás is involved in the contested “Proyecto Integral Morelos”(PIM) in Mexico. In February 2019 Indigenous community leader Samir Flores was shot multiple times outside his house to silence his opposition to the project.ii

Lobbying power: Up to €200,000 on EU lobbying in 2018; 3 in-house lobbyists; additional EU lobby groups: 18

Enagás’ EU lobbying budget increased 400% in 2014, the year Partido Popular Minister Miguel Arias Cañete was appointed EU Climate Action and Energy Commissioner. Cañete has been a key supporter of the EU-subsidised MidCat pipeline, and a key Enagás lobby target (more than 70% of its meetings with Commission elite have been with Cañete or his cabinet).iii The company is a member of 18 additional lobby groups which have 59 lobbyists in total.iv

Gas propaganda: Presents natural gas as a clean fossil fuel, essential in tackling climate change. Pushing gas in the transport sector (including so-called “renewable gas”)v with plans to make Spain a “gas hub”.

Fun Fact: Notorious in Spain for its revolving door, placing ex-Presidents, Prime Ministers and Ministers from both parties into powerful and well-paid positions on the boards of its companies.

Case study: Castor Project

The Castor Project is Spain’s largest gas storage plant, built into an old oil field 22km off the Castellón coast, close to Valencia.

It was claimed at the time that Spain needed more storage due to energy security concerns (a claim subsequently dispelled),i but after starting pre-operation activities in 2013, the multi-billion euro project was shut down after it caused more than 1000 earthquakes reaching as high as 4.2 on the Richter scale.

A year later, the construction company behind the project, ACS (owned by Real Madrid President Florentino Pérez Rodríguez), gave up the concession. However, the costs fell on Enagás and the Spanish people via their gas bills. This was due to a controversial clause included in the original concession, enabling ACS to be awarded €1.35 billion in compensation.

Enagás, acting on behalf of the state, took over the failed concession, as well as the debt for the compensation and maintenance costs. Including interest, the total cost was as high as €3.3 billion.

This case of state-subsidised corporate profiteering is being challenged by groups under the banner “Caso Castor”.ii They are taking the politicians and CEOs involved to court.

Company: FLUXYS

Country: Belgium

Name: Fluxys

Main shareholders: Publigas (77.5 %), Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (19.9%).

Publigas: Belgian inter-municipal holding company.

Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec: Quebecois public financial institution.

CEO: Pascal De Buck

Took over in 2015. Former Chairman of Swedegas AB. Earned €450,000 in 2017.

Chairman: Daniël Termont

Member of the Flemish Socialist Party (Sp.A), Mayor of Ghent until 2019.

Other board members: representatives of various Belgian political parties and the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec.

Subsidiaries: France, Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland and UK

Fluxys Belgium holds all domestic operations, while Fluxys Europe owns the European companies. Alongside Enagás, it acquired Swedish TSO Swedegas in 2015 but sold it in 2018.

Turnover: €515 million in 2018, with €54.5 million profit. Paid out €86.4 million in dividends that same year.

Controversial projects: TAP, shipping gas from the Arctic and fracking, Ghislenghien disaster.

Owns 19% share in the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP – see case-study) and has actively lobbied Brussels on behalf of the TAP consortium alongside the Azerbaijan government.i Fluxys’ two LNG terminals (Dunkirk and Zeebrugge) import gas from the Russian Arctic and fracked gas from the US. In 2004, a high-pressure gas pipeline exploded in Ghislenghien, Belgium, killing 24 and injuring 132.

Lobbying power: up to €100,000 spent in 2017 on EU lobbying; 4 in-house lobbyists; additional EU lobby groups: 8

Consistently spends between €50,000-€100,000 per year on lobbying Brussels. Its three meetings with the European Commission since 2017 have all concerned TAP. It is also part of at least 8 gas industry lobby groups in Brussels. It sits on a Commission advisory group on security of gas supply, on behalf of its lobby group Gas Infrastructure Europe. It has received €2.4m in EU grants for gas projects.

Gas propaganda: “As Belgium prepares for a more sustainable energy future, both natural and renewable gas will play an important role in achieving our national objectives.”ii

Fun Fact: Fluxys Chairman Daniël Termont claims to be a climate champion, signing Gent up to be climate neutral by 2050 while mayor of the city,iii but his gas company is locking us into fossil fuels for the foreseeable future.

Case Study: Zeebrugge and Dunkirk

Fluxys operates two liquified natural gas (LNG) terminals, Dunkirk in France and Zeebrugge in Belgium. Both are important hubs for the supply of Northwestern Europe and have emerged as key enablers – alongside terminals owned by GRTgaz, Enagás and others – for controversial new gas developments in the US and Russia.

Zeebrugge and Dunkirk have been among the main ports of call for LNG tankers from the Arctic region of Russia, ever since the Yamal gas project became operational in late 2017. Yamal LNG is part of opening a new ‘gas frontier’ in the Russian Arctic, which could both wreak havoc on a region already vulnerable to climate change, and lead to huge greenhouse gas emissions.

Fluxys is just as happy to do business with Russia’s geopolitical rival, the US. To make fracked gas economically viable, the industry has to find export markets, and Europe is a key target. Imports of fracked gas from the US began in 2016 in Portugal, and have increased in 2018, including to Dunkirk. This in turn leads to intensified fracking in the United States, with its devastating environmental and health impacts.

Company: GRTgaz

Country: France

Name: GRTgaz

Main shareholders: Engie (75%) and Caisse des dépôts (25%)

Engie’s (formerly GDF-Suez) main shareholder is the French government (24.1%), followed by BlackRock. Caisse des dépôts is a French public financial institution. A new law passed in April 2019 opened up Engie and GRTgaz to further privatisations.

CEO: Thierry Trouvé

Ex-civil servant and former director of French energy regulator. Previously in charge of Engie’s LNG business.

Chair: Adeline Duterque

Director of Engie’s Foresight Department.

Other board members: representatives of Engie, Caisse des dépôts, and the French government.

Subsidiaries: France, Germany, Mexico

Holds all of Engie’s gas transport networks, except Nord Stream II, with a particular presence in France (gas transport and LNG, via Elengy), Germany (MEGAL pipeline) and Mexico (Los Ramones Sur II, on behalf of Engie).

Turnover: €2.3 billion in 2018, with a profit of €389 million.

GRTgaz paid out around €300 million of its profits to its parent company Engie in dividends.

Controversial projects: MidCat, Eridan, SGC interconnector; Nord Stream II

Midcat, Eridan and the Southern Gas Corridor interconnector (receiving Azeri gas from the SGC via Switzerland) are all on hold due to ongoing resistance and high costs. GRTgaz’ parent company Engie is also involved in the Nord Stream II pipeline project. It is being led by Gazprom and would bring Russian gas through the Baltic, but is opposed by the European Commission and many EU member states.

Lobbying power: up to €300,000 spent in 2017 on EU lobbying; 4 in-house lobbyists; Additional EU lobby groups: 6

Lobby spending increased by around 500% from 2015-2016, but much is done via its six lobby groups and trade associations. A big focus is on so-called renewable gas, such as biomethane. It is also very active in France, where it spent up to €200,000 in 2018.

Gas Propaganda: pushing for so-called “renewable” gas, especially biomethane. Engie and its subsidiaries (including GRTgaz) want France’s gas to be 100% renewable by 2050, using primarily biomethane produced from agricultural and urban waste, controversial for its links with polluting large-scale industrial farms.

Fun fact: France has a very active revolving door between Engie and its subsidiaries, the government and the energy regulator, including top executives such as GRTgaz CEO Thierry Trouvé. Many go to the same schools and universities.

Case study: MidCat

The MidCat project was originally a gas pipeline running from Catalonia in Northern Spain to South-Eastern France. Begun in 2011, its goal was to double the capacity of gas transportation from Spain to France and increase the European Union’s “energy security”.

With strong support from Commissioner Miguel Arias Cañete,i the European Commission included it in its list of ‘Projects of Common Interest’ (PCIs) in 2015 and 2017, which gave it priority status and additional financial and political support.

The MidCat proposal evolved into a vast gas transport network on both sides of the border, encompassing 1,250km of new pipeline, including the controversial Eridan project in France. Backed by Enagás in Spain and Teréga (40.5% owned by SNAM) and GRTgaz in France, the €3.1 billion project was predicted to cause social, environmental and climate destruction.ii The original section was renamed STEP (South Transit East Pyrenees).

Work was planned to resume in 2019, but a leaked cost-benefit analysis commissioned and then buried by the EU cast doubt on the financial viability and necessity of MidCat.iii With opposition to the project growing, in January 2019 energy regulators in France and Spain refused to grant consent and funding for it.iv

However, EU Commissioner Cañete (who is close to Enagás – see company profile), continues to promote the project and it may still be included in the 2019 PCI list.

Company: Snam

Country: Italy

Name: Snam

Main shareholders: CDP Reti SpA (30.4%), BlackRock (7.5%), Romano Minozzi (6.8%), Lazard Asset Management (5.1%).

CDP Reti SpA: An Italian holding company, owned by public financial institution Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (59.10%) and a subsidiary of the State Grid Corporation of China (35%).

Minozzi: an Italian businessman. Lazard: also has 5% in Enagás.

CEO: Marco Alverà

Was with Eni for 10 years, as well as on the board of Gazprom Neft. Previously Vice-President of Brussels trade association Eurogas, and is now President of super trade association GasNaturally.

Chairman: Carlo Malacarne

Former Snam CEO who spent his whole career in the company. Previously Chairman of Confindustria Energia, the energy section of the main industrial trade association of Italy.

Subsidiaries: Italy and Europe

Assets in Italy (transmission system and LNG terminal), Albania (AGSCo), Austria (TAG and GCA), France (Teréga), Greece (DESFA) and the UK (Interconnector UK). It is a shareholder of TAP (20%).

Turnover: €2.5 billion in 2018, profit of €1 billion

Paid out €735 million in dividends in 2018

Controversial projects: Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP); Rete Adriatica

SNAM holds the joint-largest stake in TAP with 20% (see case study), the last leg of the Southern Gas Corridor from Azerbaijan, which is facing strong popular opposition in Italy and Greece. It is supposed to connect to the Rete Adriatica, a 700km pipeline being built in Italy by Snam through an area prone to major earthquakes. There has been opposition to it since its first proposal in 2004.

Lobbying power: up to €300,000 on EU lobbying in 2018; 3 in-house lobbyists; additional EU lobby groups: 10

Snam has had 26 meetings with top level EU Commission officials since 2015, many concerning TAP and the Southern Gas Corridor. It is very well represented in Brussels thanks to its 10 lobby groups, in particular GasNaturally, chaired by Snam CEO Marco Alverà.

Gas propaganda: Pushing for biomethane and small-scale LNG to be used in transport. Also keen on wrongly reassuring the public that “Natural gas is the greenest and most efficient fossil fuel and is an indispensable energy source for a sustainable energy mix”i (See ‘gas – a false solution’)

Fun Fact: SNAM is involved in more projects to complete the EU’s so-called ‘Energy Union’ than anyone else, building more km of pipeline and more gas storage facilities than any other company.

Case study: Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP)

The Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) is the last section of the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC), a 3,500 km pipeline from the Caspian Sea in Azerbaijan to the South of Italy, with a US$ 45 billion price tag. TAP is supposed to run from Greece through Albania, under the Adriatic Sea and arrive in Puglia.

Its current shareholders are BP, Socar (the Azerbaijan state-owned gas company), Snam, Fluxys, Enagás and Switzerland’s Axpo. The company is registered in Zug, the most secretive Swiss canton. The initial project was elaborated by a company controlled by Axpo whose CEO has been allegedly linked to money laundering for an Italian organised crime outfit.i

Both TAP and the SGC are “Projects of Common Interest”, deemed strategic by the European Commission. TAP was selected in June 2013, against a backdrop of aggressive lobbying and alleged corruption by Azerbaijan at the Council of Europe, where a report highlighting human rights abuse in the country was infamously voted down.

Initially TAP was presented as a “private sector project”. However, EU public funding may cover up to one third of the total costs. In 2018, the European Investment Bank, (EIB), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, (EBRD), and a number of private banks approved €2.7 billion in loans despite opposition in Italy, Albania and Greece. Independent evaluations also found the project failed to comply with international standards for financial institutions.ii

In March 2017, thousands of police officers were sent to ensure building work in Italy, involving the uprooting of hundreds of olive trees, went ahead, against the non-violent resistance of residents. Since then, every new step on the construction site has been taken through special authorisation via government decree and under significant police presence.

Be the first to comment