The social failures of Brexit are, in one sense just part of a long history of social failure in a Britain dominated by England, an England dominated by the richest subjects of the monarch, people who mostly have at least one home in London.

Danny Dorling is Professor of Human Geography at the University of Oxford

Cross-posted from Danny’s Blog

Photo: Sudzie/Creative Commons

‘Fifty years on from now, Britain will still be the country of long shadows on county [cricket] grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers, and—as George Orwell said—old maids bicycling to Holy Communion through the morning mist.’

John Major’s speech to the Conservative Group for Europe, 22 April 1993

Thirty years ago, the Prime Minster, John Major, suggested we had little to fear, that Britain would still be a country in which county cricket would be played in a weird English game where nothing much happens and no one really cares what the result is (when the match is ‘county’, meaning not international). He was describing the antidote to what was becoming an increasingly competitive and driven world, a society with increasing aspirations for excellence and productivity. County cricket implies that good enough is good enough, that it is ok to ‘coast’. Warm beer is good enough.

Warm beer may be an acquired taste and often not excellent, but it was our taste. Suburban housing was the least efficient way to house people ever invented, but it was our invention. Our British dog breeds would remain loyal and obedient, just as long as we followed Barbara Woodhouse’s advice, a darling of the 1980s British media, who promised ‘no bad dogs’ for followers of her books and television shows. We had British birds and British trees too, and when the middle class bought their children books they included titles, such as ‘one hundred British insects and invertebrates to identify in your British pond’. A few such items still exist from that past and some new posters are made each year for those who like them.

Old maids could cycle happily and pray contentedly because they were English and England was that country which Mary Whitehouse was keeping safe from smut. We were part of the European Economic Community, but that would all come to an end shortly before Christmas 1993 after which we became a member of the European Union. We were also, and continue to be, the lowest social spending and (for the affluent) the lowest tax regime of any large country in that Union. Only Spain shortly after Franco had been in charge, and Greece shortly after the junta of the generals, spent less on public services.

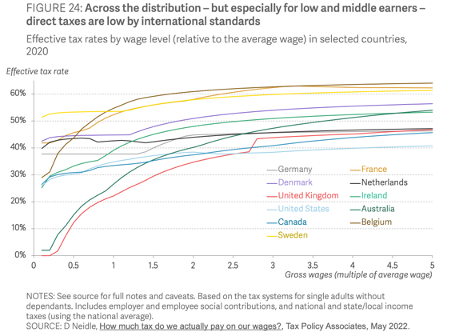

As the Resolution Foundation explained three decades later, ‘‘Tax policy choices help determine levels of inequality’, and UK politicians had not, in the immortal lyrics of Wham, chosen life, they chose instead, inequality.

The social failures of Brexit are, in one sense just part of a long history of social failure in a Britain dominated by England, an England dominated by the richest subjects of the monarch, people who mostly have at least one home in London.

In no other large country in Europe did people pay so little in direct taxation as in the UK in 2016 when the referendum was held. The poor paid very highly in indirect taxation, including through VAT and taxes on some particular goods that they more often consumed. But the poor in the UK had so little money that those taxes did not raise enough to sustain a well-functioning state in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s. Things were slowly falling apart. And we blamed the foreigners, the immigrants, immigration, and the European Union for allowing that immigration and all its weird rules (the ones that mostly only ever existed in our imaginations).

Note: the well-off pay very low taxes in the UK too, those earning 4 times average incomes pay the least in Europe.

We have a tendency to remember the past differently to how it really was, and to see aspects of places as being unique which are actually much more universal. John Major in 1993 claimed that England was a country of long shadows, but the shadows were no longer than elsewhere in the remains of the day of our youth, and no different to shadows elsewhere in the world at our latitude. There are no special British shadows.

So too with the morning mist, the dogs, the beer, the greenery. Suburban gardens in England are not some special and unique British green. But in one way Britain was already very different from other European states by 1993. No other state in Europe had just experienced such a huge rise in economic inequality – not one – and the social repercussions that followed from that.

John Major had been the last of Margaret Thatcher’s string of Chancellors of the Exchequer, the last of the men who presided over the fastest recorded tearing apart of the social fabric of a nation. He had followed in the footsteps of Geoffrey Howe and Nigel Lawson. None of these Conservatives saw how they had cast dark shadows on a society to the extent that that there was, in Thatcher’s own words, no longer such a thing as society (‘…There are individual men, and women, and there are families’ – she said, and too few asked why she thought that).

Conservative Britain was the imagined corner of a cul-de-sac, separated from its neighbours by a small stream, that would forever remain the same. Tory England, they believed, would be forever a powerful sceptred isle, another Eden, a demi-paradise, home to a happy breed of men, the envy of less happy lands, a blessed plot, a teeming womb of royal kings, of the true chivalry and of all those so numerous Christian religious services towards which old maids rode on cycles in the mist.

Almost a decade after John Major had tried to reassure the English that joining the European Union would alter nothing, at a private dinner in Hampshire in 2002, Margaret Thatcher was asked what her greatest achievement had been. She replied: ‘Tony Blair and New Labour. We forced our opponents to change their minds’. New Labour then did nothing of any substantial effect to reverse the huge rise in inequality that John Major and his predecessors had socially engineered. Resentment and mistrust of others festered and grew.

.. continues (at great length)….

for the full report as a PDF and where it was originally published click here.

Thanks to many generous donors BRAVE NEW EUROPE will be able to continue its work for the rest of 2023 in a reduced form. What we need is a long term solution. So please consider making a monthly recurring donation. It need not be a vast amount as it accumulates in the course of the year. To donate please go HERE.

Be the first to comment