Every aspect of our personal lives is fleetingly the subject of intense political debate, while the big questions of our epoch are left to the powerful to resolve

David Jamieson is editor of Conter, a Scottish anti-capitalist website.

Cross-posted from Conter

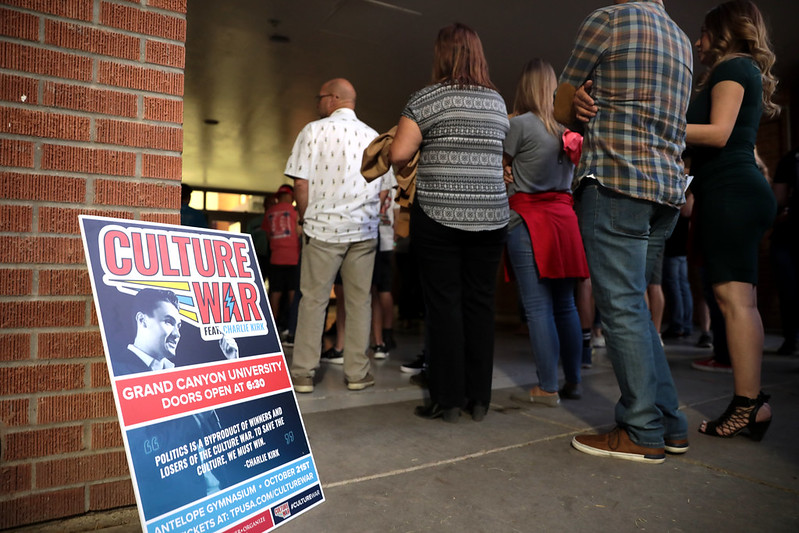

The chances are you had better things to do last week, but journalists were transfixed by something called the National Conservative conference in London. Billed as an attempt to revivify a conservative agenda flagging after 13 years of Tory rule that have failed to solve Britain’s underlying social and economic problems, it instead demonstrated that thinkers on the right have succumbed to the strange mix of high drama and triviality we call the culture war.

Most of the speakers at NatCon were gum-flapping chancers who trade in anodyne observations and bovine insults. The cartoon narrative historian David Starkey made a fool of himself, as he can be expected to at every public appearance. Melanie Phillips was, dependably, the rictus grin of suburban British idiocy, proof that you can be so middle class that you turn into a peasant.

Speaking of rural affairs, the Tory party released a paddock of horses onto the conference floor. Each MP and cabinet member I saw managed to combine dull, spiritually ugly and uncomprehending in different combinations.

Big brains were largely absent, but so was charisma. Where was Nigel Farage, for instance? What made him want to dodge this occasion? True, he’s an arch economic liberal – but so were a great many of the speakers. Some, making eulogies to Thatcher and Regan, had apparently missed the memo on what the conference was supposed to be about – a post-libertarian reboot for rightwing ideas combining economic and social communitarianism – that dread political synthesis constantly being threatened and feared but never materialising.

Other speakers, like Michael Gove, even warned against any drive towards populism. NatCon was, he must have thought, a very un-British kind of conservatism. All rather vulgar, immodest and intrusive. Of course, the Tory party has never really been the home of moderate ‘warm beer and cricket grounds’ anti-politics that its hagiographers swoon over. But nor, in recent years, has it tended to hector women for not having enough babies, and without an ounce of charmingly repressed seaside humour. We are looking at neither Blackpool Pleasure Beach nor the Home Counties fete, but Bible-belt on the Danube.

In response to the conference, many on the culture war left reanimated a favourite argument: NatCon proved the necessity of the culture war itself.

For some, the culture war is the place where the real struggle for the future takes place. According to Adam Ramsay, when issues capture public debate, this is because they: “…tap through rotting pillars holding up our traditional social hierarchies and allow us to see beyond. Other ways of understanding the world begin to come into view… and, gradually, some of these new structures of feeling spread throughout a society and become the new common sense.”

“That is what conservatives fear the most.”

The argument gains credence when it is echoed on the culture war right: “Many now understand that, unless they do something, they will lose much that is precious. They feel that they have no choice but to defend their way of life.”

So goes the argument – should we not meet with, and defeat, the National Conservatives and their fellow-travellers in the battle of ideas, we will end up being persecuted by them in more desperate circumstances. The oppressive atmosphere of anxiety that accompanies the culture war – the permanent feeling that we have reached some decisive moment in a contest between stark civilisational alternatives – is present in this argument, just as it was at the conference itself.

It would be hard to over-emphasise the similarities at both ends. My argument here is not that of the handwringing centrist scribe – that populist left and right are marked by the same political militancy and commitment to rigid dogma. Quite the opposite. Culture war left and right share a gesture to radical critique, subversive aesthetics, heated rhetoric and righteous conflict. But at the core of both worldviews is (small c) conservative politics – which is to say, establishment liberalism. Indeed, all the most dangerous ideas discussed at the conference are already government policy.

Over the great questions of the hour, the average NatCon speaker and the average critic of the event share a politics in common. To take one example, the war in Ukraine – the most important issue of our time and then some – went little mentioned. Anything said would have been readily agreed to by the culture war left, and that doesn’t make for a very good culture war.

In a sense, it is agreement itself which generates the heat. But there is more than the narcissism of small differences in play. Culture war reflects the desire for agency and meaningful conflict, in the absence of real political contestation with clear, decisive consequences.

Those of us who reject the culture war are often charged with stuffiness or philistinism – rejecting the real, current tensions in society for idealised versions of struggle. ‘Culture’ may not be downstream from politics, goes the argument, but it still has real significance and it is here, now.

There’s a failure of terminologies here. The ‘culture’ war label is, of course, a hand-me-down from a past generation. A better title for the phenomenon has been awarded by Anton Jager, who refers instead to ‘hyper-politics’.

In the hyper-political mode we inhabit, everything is politicised, especially popular culture. But much that characterised political contestation in the 20th century – particularly the construction of mass political organisation, remains elusive. Instead, we are fixated by the fleeting, faddy and peripheral. Moral, lifestyle, and aesthetic questions dominate this rabid political transference. Indeed a scroll through NatCon lecture titles will demonstrate that almost all the chatter is instruction on how people ought to conduct their own private lives – how they should raise their children being a particularly intense obsession.

As living standards deteriorate and war tensions mount, as the public realm becomes more chaotic and unstable, we drive deeper into the private realm. Not content with policing each other’s private lives, we increasingly interrogate psychological states – even the unconscious (you’ll remember when Keir Starmer was audited for unconscious bias). As the rich struggle over market space, geostrategy and tech competition, we mirror them in a feeble key by attacking each other in our world of little power and less property. In the downstairs to their upstairs.

This is why nothing in the downstairs fight holds our attention. Last week, the NatCon conference was an urgent call to arms for the right – the beginning of a revolution against ‘woke’ cultural hegemony, and so forth. For the left, it reeked of impending fascism. But for all the drama and diagnoses, it was forgotten within days by partisans on all sides. Dire warnings are constantly issued, wallowed-in, then swiftly forgotten as the next Hollywood film, public statement, celebrity affair or micro-controversy takes hold.

There will have been intelligent conservatives at NatCon – I’ve no doubt. People can be fruitfully wrong about the world. They could have had insightful things to say, and serious challenges to make of complacent ideas or institutions, if only they were surrounded by a political culture more conducive to this. As it is, they are locked in dubious battle with equally confused opponents. All victims to the end, all cowering and shrieking at shadows in a time where authority is unpopular and unsought. I’m talking about the right here, but I’m obviously talking about all too many on the left as well – blinkered, choosing political priorities based on what ‘that lot over there’ are thinking and doing.

I finish with a reminder of times when the right still had something to say, or at least knew how to turn a phrase. Here’s an aphorism from Friedrich Nietzche: “Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.”

Hyper politics is an abyss. Don’t get sucked in.

Thanks to many generous donors BRAVE NEW EUROPE will be able to continue its work for the rest of 2023 in a reduced form. What we need is a long term solution. So please consider making a monthly recurring donation. It need not be a vast amount as it accumulates in the course of the year. To donate please go HERE.

Be the first to comment