The EU Commission is claiming success in reducing the number of jobless young people in the European Union. A closer look at the statistics reveals that the situation is anything but positive.

Karl Brenke is an Economist at the the German Institute for Economics (Deutsches Institut für Writschaft DIW) in Berlin.

Odd that we rarely hear anything about EU youth unemployment nowadays. A few years ago European media was full of reports about large numbers of jobless young people. In Spain, for example, this was purportedly 50%. Why has the topic disappeared from the headlines? Has the problem been solved? Has the EU achieved a miracle with its „Youth Guarantee“ programme of 2013, a commitment to ensure that all young people under the age of 25 receive a good quality offer of employment, continued education, apprenticeship, or traineeship within four months of becoming unemployed or completing their education, or has the subject simply become less important?

How could youth unemployment in the EU have fallen so radically, while employment of young adults has hardly increased?

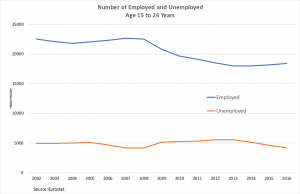

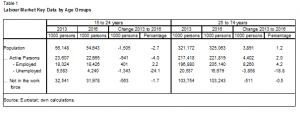

Labour researchers define “youth” or “young adults” as 15 to 24 year-olds. Unemployment for this group increased until 2013, but decreased by 1.3 million to 4.2 million by 2016. Strangely in the same period the number of employed young adults rose only by 400.000. Why this discrepancy of almost one million jobs? To understand this we need to examine the statistics since 2013 more closely.

The increase in employment is not the only factor responsible for the reduction in the number of young jobless in the EU. Two other aspects play a major role. Firstly, the number of 15 to 24 year-olds in the EU declined by 1.5 million between 2013 and 2016. This is a result of the sinking birth rate in past decades. Secondly, and this is a bit more complicated, the behaviour of the labour force has changed. If you take the sum of employed and unemployed seeking work, and compare it with the number of all members of that age group, you have the “labour force participation rate” – those actively engaged in the labour market. In 2013 this participation rate was 42 %, in 2016 41.5%. This decline may appear minimal, but it means 300.000 fewer young people were seeking jobs in 2016 than in 2013, thus disappearing from the statistics.

Young adults have hardly benefited from the recent increase in EU jobs. While the number of employed 15 to 24 year-olds increased 2.2% between 2013 and 2016, the number of older workers with jobs grew by 4.4%.

The demographic development will continue to reduce youth unemployment

The continuing decrease in the birth rate in the EU points to a further reduction of youth joblessness. At the beginning of 2016 the number of children in the EU between 5 and 14 years was 2.9 million less than young adults between 15 and 24. In the future that means on average 290,000 fewer young adults needing work each year – unless immigration increases.

We do not know if the labour force participation will continue to drop. In the first decade of the millennium it was more or less constant. It first began to fall because of the financial crisis and continued to do so until 2015; since then it has remained stable. Should the situation on the labour market improve, the participation rate could rise. On the other hand, young people are studying longer to improve their job qualifications. Thus many are postponing their entry into the workforce.

The percentage of young people in the EU attaining a university degree or an equivalent has increased from 7% in 2006 to 9% a decade later. For the next age group, 25 to 29 years, it has risen from 29% to 37%. This has a lot to do with developments on the labour market: if there is a shortage of jobs, people tend to study longer to improve their qualifications and thus their chances of finding work.

The number of young adults in the EU workforce is low

The number of young adults participating in the EU labour market, at 41.5%, is very low. That means a large majority is currently in training, studying, or not looking for work. The media reports in 2013 of over 50% youth unemployment in Spain were therefore incorrect. How could half the young adults in Spain be unemployed, when not even half were working or actively seeking a job. Only one in five of these young adults on the labour market could not find a job. 20% youth unemployment is nonetheless a very sobering number.

Diverging development of youth unemployment among EU states

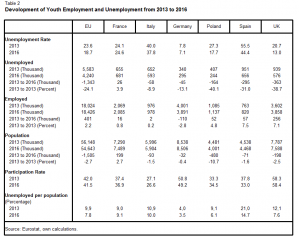

The unemployment rate of young adults among the EU nations differs considerably. In table 2 below only the larger EU nations are listed: France, Italy, Germany, Poland, Spain, and the United Kingdom. In almost all these countries the rate of youth unemployment sank between 2013 and 2016, but, with the exception of the UK, this was a consequence of factors other than growth in the number of jobs for young people.

The exception was France. There the rate of youth unemployment increased, which had a lot to do with the growing number of 15 to 24 year-olds. The only reason the unemployment rate was not higher was a marked reduction in labour market participation by young French adults.

In Italy employment stagnated, but youth unemployment decreased because of a reduction in the number of young adults and their rate of participation in the labour market. Germany was a special case. Although there were fewer 15 to 24 year-olds with jobs in 2016, as in Italy the number of young adults and their rate of participation in the labour market declined, resulting in a decrease of youth unemployment.

Youth unemployment shrank the most in Poland. This had less to do with increased employment, than with a hefty drop in the number of young adults in Poland. Although attributable to a small degree to a falling birth rate, the main cause was immigration to other EU nations.

Also in Spain youth joblessness has dropped dramatically, but is still very considerable. This is mainly the consequence of a significant decrease in labour market participation. Because of a lack of jobs many young Spaniards have given up looking for work and thus are removed from the unemployment statistics.

The increase in the number of jobs has had little effect on the rate of youth unemployment. The only exception was the UK. Although the number of young adults is slightly smaller, the rate of participation in the labour market remained constant. The decline in youth joblessness in the UK was mainly the consequence of increased employment.

These statistics provide a very mixed picture: With the exception of France, youth unemployment in the largest EU nations has declined – but only in the UK is that decline due principally to an increase in jobs. The reduction of youth unemployment in other nations was mainly the effect of a diminishing number of young adults and the fact that many turned their backs on the job market.

Less qualified workers are often unemployed – in the case of young adults, even skilled workers have a hard time finding a job

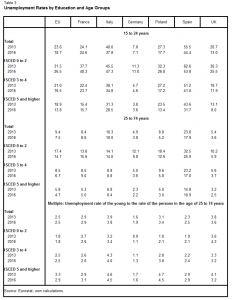

The fewer qualifications one has, the greater the chance of unemployment. Over a quarter of young people with just a lower secondary education are unemployed; a sixth of those with a secondary education that prepares them for labour market entry or university; and, approximately one seventh of those with technical training or a university degree. This is applicable in all larger EU nations although in countries with high youth unemployment, like Spain, young adults with only basic education have a still higher jobless rate.

As the youth unemployment rate has decreased in most EU nations since 2013, so has the number of jobless young adults with only a basic education. There are however major exceptions. In France, where the rate of youth unemployment has not fallen, joblessness among 15 to 24 year-olds with a basic education has increased. Although youth unemployment in Italy sank somewhat, 47% of young adults with only a basic education are without work – almost as many as in Spain.

If we compare youth unemployment with unemployment among people 25 years and older, we discover it is 250% higher. This has hardly changed in the past few years – even in the EU’s largest nations. This ratio is lowest in Germany and especially high in Italy, the UK, and Poland.

The rate of unemployed academics among young adults and their older peers is also markedly higher. This means that joblessness among young adults is not only or not mainly a question of qualifications.

New jobs of young adults are almost exclusively temporary employment and part-time

Even though youth employment in the EU has increased in the past few years, we have to ask what sorts of jobs have young adults obtained.

In the EU half of the recently created jobs for young adults were part-time employment, raising the average rate of 15 to 24 year olds with part-time jobs to one third. In Spain and the UK the proportion is much higher. In France, Italy, and Germany part-time employment among young people has increased, while the number of full-time jobs has declined. Poland is the exception. There the number of young people with part-time jobs has decreased and full-time employment has risen for all age groups.

Young adults in the EU are especially vulnerable to temporary employment. 44% of them have temporary jobs. Among workers older than 24 years the rate is only 11%. This glaring difference might be explained by young people having temporary contracts during their training or when they receive their first jobs. Still the difference between the two age groups is astonishing.

Generally – for young and old – temporary employment in the EU has increased considerably since 2013. In the case of young adults the modest increase in employment consisted almost exclusively of temporary jobs. The exceptions are the UK where, part-time jobs are less common, the number of full-time work for young people has increased, and Germany. In Spain and Poland more than 70% of young adults have temporary jobs.

The EU Commission is ignoring the facts

The EU Commission claims to have turned around youth unemployment, reducing the number of young people without jobs with its „Youth Guarantee“ programme (http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1079&langId=en): “10 million young people took up an offer, the majority of which were offers of employment.” That is a rather astounding claim, seeing that the number of jobs for young people in the EU only increased by 400,000 (an increase of 500,000 employees and a loss of 100,000 self-employed) since the programme was introduced in 2013. The decrease in youth unemployment is more a result of the diminishing number of 15 to 24 year olds in the EU, as well as more young people postponing entering the labour market, instead studying longer or selecting other options. This probably is simply because the job market is so desolate. If, as the EU Commission claims, their youth employment programme was so successful, why has the employment rate of all other age groups increased at a much greater rate?

The EU Commission’s claim is additionally dubious as almost all of the new jobs for young adults are temporary, and half of those were only part-time. There may have been an increase of full-time jobs for EU workers over 24 years of age, but many of these too are temporary. Temporary jobs seem to be the trend in the EU; this indicates that the labour market is still difficult and workers have little leverage to obtain better contracts. The current situation is especially unfavourable for young adults because their rate of unemployment rate is two and a half times greater than older age groups. In the case of young people with excellent qualifications the difference is oddly enough even greater.

The EU Commission is conveniently ignoring these facts.

Be the first to comment