If price stability really is the mandate of Central Banks, then why don’t they crack down on the main driver of price inflation – fossil fuels?

Ewan McGaughey is a Reader in Law, specialising in employment law and enterprise law, at King’s College, London.

Cross-posted from the LSE Politics blog

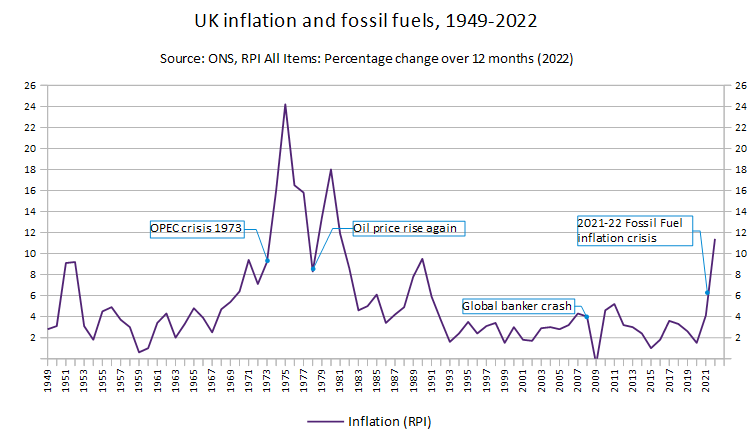

A fossil-fuelled inflation crisis has struck Britain, and other countries dependent on oil and gas, for a second time. The first was the OPEC crisis, in which oil producing countries raised prices fourteen-fold from 1973 to 1979. The second began as Vladimir Putin prepared his criminal war on Ukraine in 2021, and gas and oil prices were raised to finance the invasion. Hiked energy prices cascaded through the economy, raising road transport, agricultural and shipping costs, and cutting real wages. Saudi Arabia, Qatar and other dictatorships restricted their supplies like Russia, while the Big 4 – BP, Shell, Exxon, Chevron – profited over £100 billion in 2022 alone by raising their prices.

The Bank of England, like the European Central Bank, the Fed and others, have legal mandates to maintain “price stability”. Yet as long as fossil fuels are used, boom and bust will beckon. The Bank of England and others must use the multiple legal powers they already have to steer the economy away from fossil fuels. They should do this, not add to inflation by raising mortgages, rents and borrowing costs. Their action or inaction is subject to judicial review.

Costs as changeable as the climate

Why do fossil fuel create systemically unstable prices? First, markets in gas, oil and coal involve a total failure of competition. Every oil, gas and coal field is a natural monopoly, where prices would rise with more producers, and with huge barriers to entry. The world markets are a cartel. OPEC says it has 80.4 per cent of world crude oil reserves (1,240 billion barrels in 2021), while the Big 4 said they held about 56 billion barrels in 2021, and took £150 billion profit in 2022. The countries producing most oil are dictatorships. They are a proven threat to security, and they always manipulate prices.

Second, fossil fuels create mass externalities. At current burning rates, our planet will reach over 1.5 degrees Celsius of heating in the next four years. This means reserves are worthless and must stay in the ground to abide by the 2015 Paris Agreement targets. The use of fossil fuels must end, or life as we know it will. Currently, a surge in litigationis underway that is likely to make corporations pay for the harm they have caused, and could make executives personally liable, as in the Dieselgate scandal. This makes gas, oil and coal the riskiest assets to hold. When not soaring, fossil fuel prices are prone to collapse, with the risk of mass volatility and loss for all investments and savings.

Third, fossil fuels are technologically obsolete. Horses were not abandoned for 50 years after the Model-T Ford was first mass-produced, but no matter how slowly markets worked, they were obsolete. Gas, oil and coal are more expensive, and less efficient than clean power, and hydro or other energy storage. Clean vehicles are cheaper to own and run than petrol or diesel vehicles, which will be banned imminently. Fossil fuels are only still in use because networks create a status quo bias that (left to itself) takes time to shift. Because political reaction and change is unpredictable, this makes the value of fossil fuels inherently likely to become more and more erratic, creating further price instability.

Price stability is a legal objective of central banks

If central banks worldwide have a duty to safeguard “price stability”, then fossil fuels must be confronted openly. The Bank of England’s mandate is to “maintain price stability”, and then support government’s “objectives for growth and employment”, and economic policy. The European Central Bank’s primary objective “shall be to maintain price stability” and “support the general economic policies in the Union”. The US Federal Reserve has goals for “maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates”. The law requires action for stable prices, and to mitigate spikes in inflation, such as those shown in the graph below.

The legal mandate recognises that inflation enables asset owners, as John Maynard Keynes once wrote, to confiscate citizens’ wealth – and they “not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some”, like “a gamble and a lottery”. Price stability is a prime social goal to stop asset owners taking other people’s money. In the case of fossil fuels, the asset owners are the coal, oil and gas polluters, and their toxic energy networks. They are arbitrarily confiscating everyone’s wealth – torching our planet for the sake of a few bob.

Central banks have four main tools to end fossil fuels

Each step towards clean power fulfils the “stable prices” mandate, and each inaction is a breach. First, central banks can require banks to set aside higher reserve requirementsfor certain assets. The Basel III requirements after the global financial crisis required higher reserves when risky derivatives were held. The same must apply for fossil fuels. If banks hold loans to, or securities of, fossil fuel companies, reserves should be raised to reflect fossil fuels’ economic, political and environmental risks.

Second, central banks can set the rates at which they lend to other banks. These rates could be split so that lower interest is charged to banks with no fossil fuel trading, and higher interest is charged to banks with more. This would effectively create a basic “base rate”, and then an additional rate or set of rates for banks with greater toxic exposure.

Third, a central bank may instruct banks in their lending or deposit policies. For example, the Bank of England may, if “necessary in the public interest” and “if so authorised by the Treasury, issue directions to any banker for the purpose of securing that effect is given to any such request”. The Treasury may in turn give directions to the Bank, though where it involves monetary policy there must be “extreme economic circumstances”’. Today’s super-inflation, and the longest fall in UK wages since the industrial revolution, constitute “‘extreme economic circumstances”’ To reduce price instability, options include:

- raising interest, or ceasing lending, to all fossil fuel infrastructure and transport, and reducing interest for clean power and storage projects;

- raising interest, or ceasing lending to manufacture or construction designed for fossil fuel use (e.g. petrol cars or buildings with gas), and reducing interest for clean power and storage projects;

- refusing and closing down deposit accounts from fossil fuel enterprises, major investors and their executives.

Fourth, with “open market operations”, central banks buy and trade vast quantities of securities, often called “quantitative easing”, to try and stabilise interest rates or whole currencies. By December 2022, the Federal Reserve held $8.5 trillion in assets, the ECB €3.4 trillion and the Bank of England around £895 billion, much of it including corporate securities, without any clear policy against unstable fossil fuels. To foster price stability, central banks should cease buying bonds or any other financial instruments connected to gas, oil and coal. Any voting rights with securities should be actively cast to shift to clean energy.

The case for urgent intervention

If we want to end inflation, the clearest path for the Bank of England, the ECB, the Fed and central banks worldwide to fulfil their mandate is to use every tool to reduce and remove fossil fuels. Price stability is inherent in a clean energy economy, because nobody can monopolise the wind, the sun or the rain. With hydro storage, heat pumps, turbines, panels and electric motors, all the technology exists, and at a scale, to be cheaper than fossil fuels already. But markets do not change themselves. Markets need positive social action, by governments, banks and business, armed with the right ideas and the right incentives. The discretion of central banks is broad but does not include failure to act at all. It does not allow life support for assets that drive price instability. As public authorities, central banks must take into account everything that is at stake, and the imperative of achieving price stability, by ending the use of toxic coal, oil and gas, also protects our right to life.

Be the first to comment