The era of the Great Divergence has come to an end, but there is a rapid, and more recent, economic divergence across the Global South.

Ewout Frankema is Professor of Economic and Environmental History at the Social Science Department of Wageningen University and is research fellow of the UK Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR)

Cross-posted from VoxEU

Recife, Brazil Photo: Wilfred Rafael Rodriguez Hernandez/Creative Commons

The Great Divergence debate has been the field-defining conversation in economic history for the past 25 years. This debate revolves around the question why the Industrial Revolution originated in Western Europe, and more specifically in Britain, and not in China, India, or Japan. By unifying scholars around this comparative research agenda, the debate has done much to globalise the field of economic history and to stimulate the construction of world-spanning databases on historical GDP, real wages, skill premiums, government revenues, terms-of-trade, human capital, land use, and more. Such data collection and estimation efforts, in turn, have provoked heated discussion on the methodological and theoretical underpinnings of income and welfare measurements, and on the critical importance of reciprocity in comparative economic historical analyses. As is the case for all major academic debates, however, at some point of their life cycle decreasing marginal returns are inevitable. Once original questions fade as new adjacent windows of exploration open. Moreover, the long era of the Great Divergence – which is primarily, but not exclusively, understood as a Eurasian phenomenon – has come to an end with the rapid economic ascendance of Eastern Asia, and China in particular. As Ken Pomeranz already observed in his seminal book The Great Divergence (Pomeranz 2000), the last quarter of the 20th was characterised by impressive rates of convergence, not divergence. In light of both developments, the academic and the historical, in a recent paper (Frankema 2023) I ask: what are the new comparative horizons in global economic history?

Beyond the Great Divergence

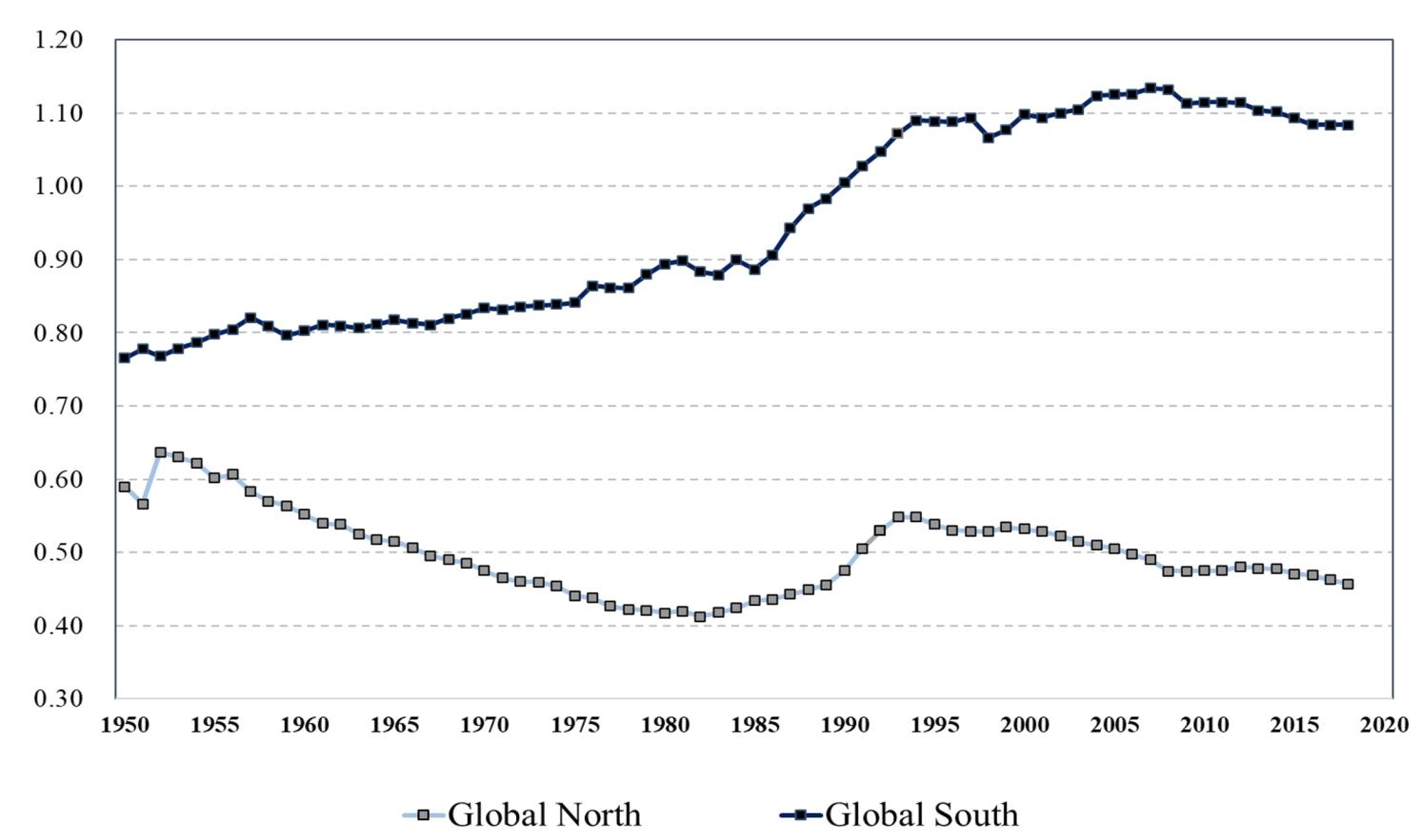

I argue that there is an urgent need to focus on the rapid, and more recent, economic divergence across the Global South. I refer to this new divide as South-South divergence. As the Eurasian gap in economic, industrial, and technological capacity began to shrink, the South began to experience growing disparities in labour productivity and per capita income. This process of South-South divergence is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows the coefficient of variation of per capita GDP in the North and the South since 1950. In the South the income disparities widened, while in the North they narrowed, a trend that was only temporarily interrupted by the disintegration of former communist economies during the 1980s and 1990s. This phenomenon of South-South divergence warrants more attention than it has received thus far.

Figure 1 Coefficient of variation of per capita GDP in the Global North and Global South, 1950-2018

Source: GDP per capita from Maddison Project Database 2020.

Note: The coefficients of variation in GDP per capita are taken from a constant sample of 40 Northern and 105 Southern countries listed in Appendix 1. The Global South excludes the oil-rich Gulf Countries; the Global North excludes the former Soviet states that gained independence in the 1990s.

To be sure, the attention that has been devoted to the economic history of developing regions has greatly increased over the past two decades. New research networks, conferences and journals have been established. However, for the most part, these research communities have lacked an explicit trans-regional comparative agenda. They have made great progress on debating topics such as Latin American inequality, African colonial legacies, Middle Eastern culture and religious institutions, or comparative patterns of Asian industrialisation, but seldom do these communities venture out to discuss the nature and drivers of cross-regional divergence. Economic historians have yet to define an agenda to analyse the causes and consequences of divergence in the Global South.

Why care about South-South divergence?

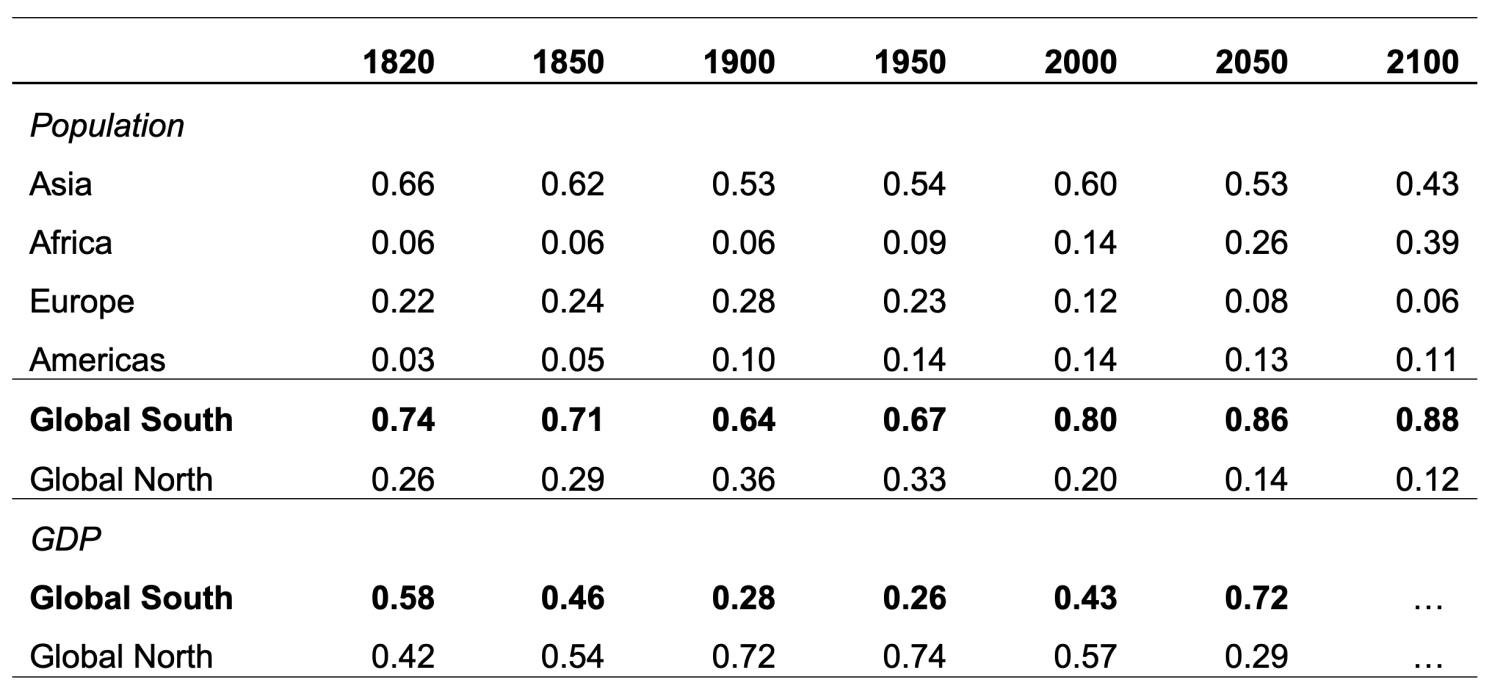

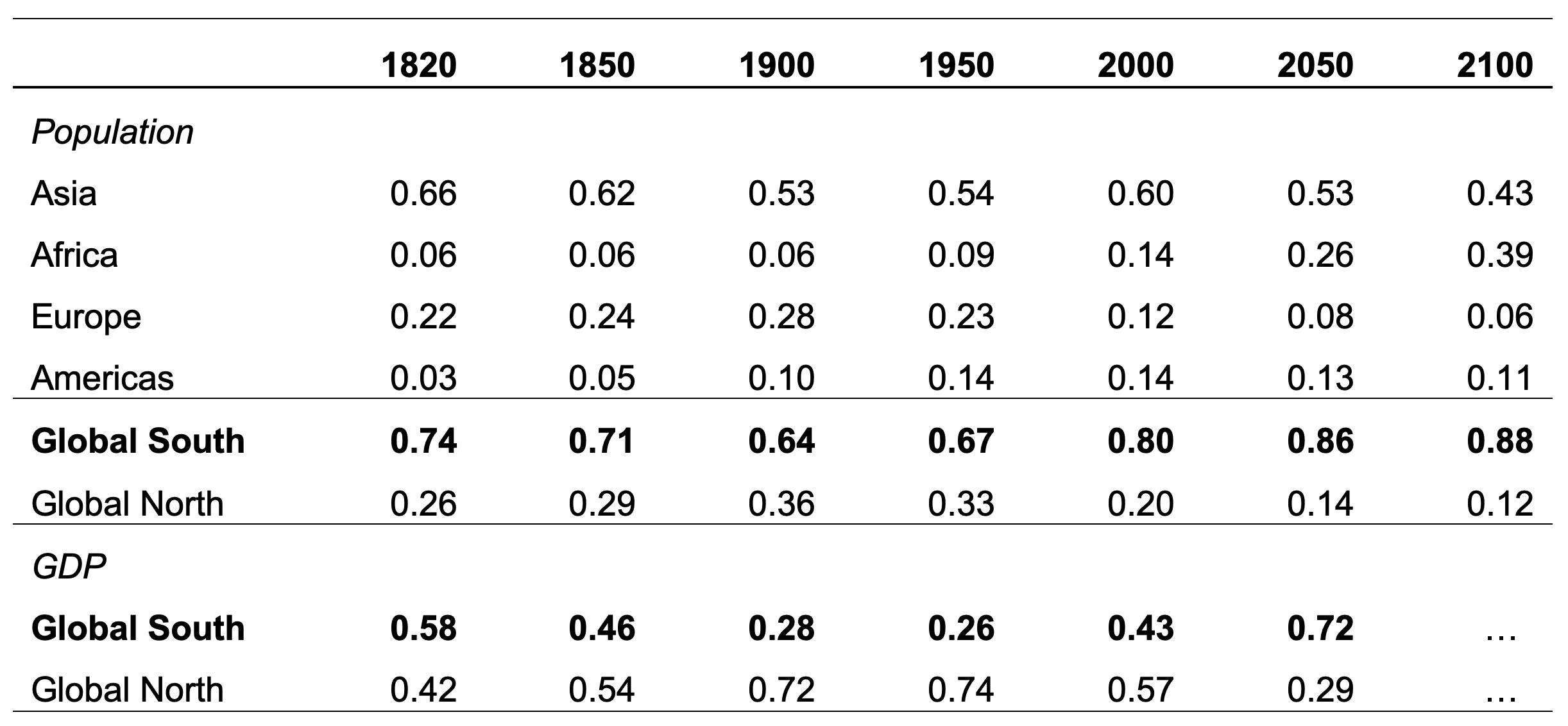

Let me offer four reasons. First, whereas the Global South today already comprises more than 80% of the world population and generates close to 60% of world GDP, its demographic and economic weight is bound to increase further during the 21st century. By 2100 the North is projected to hold just 12% of the world population, while Asia and Africa together will harbor more than 80% of the world population. The share of world GDP that will accrue to the South is projected to rise from 57% in 2020 to 72% in 2050.

Table 1 Population and income shares per world region, 1820-2100

Source: 1820-1900 from Maddison Project Database 2020; 1950-2100 from UNDP, World Population Prospects, 2022 revision, medium variant.

Note: Europe includes all former Soviet republics and Central Asian states; Asia includes New Zealand and Australia.

Second, this reconfiguration of global economic gravity is having profound implications for global divisions of labour, capital flows, trade, food demands, investment, and migration patterns. In fact, one of the most important consequences of South-South divergence has already materialised: the problem of extreme poverty, which had long been a predominantly Asian phenomenon, has shifted decisively towards sub-Saharan Africa. While back in 1990 more than four out of five of the world’s extreme poor were living in Asia, in 2020 two out of three of the world’s extreme poor lived in Africa (ca. 65%).

Third, economic history students who have to be trained in recognising, studying, and interpreting the drivers of long-term divergence and convergence will have to be introduced to these global shifts in order to make sense of them. But where is the literature that we prescribe to teach the chapter on South-South divergence? After all, the Great Divergence did not just end with the era of the Great Convergence (Baldwin 2016), it also shifted the locus of global inequality, a shift that is reconfiguring the 21st century world economy with dazzling speed.

And finally, fourth, in a field that has long been dominated by Western-centred research agendas and North-South perspectives, more systematic engagement with South-South comparisons can lead to new data collection efforts and can help to develop reciprocal comparisons without taking Western economic development as the mirror image. In this regard, the South-South divergence agenda can take the call for reciprocal comparisons to a next level. Western imperialism may play an important role in understanding the roots of South-South divergence, but it does not have to serve as the ultimate benchmark to measure performance.

Is the South a useful category?

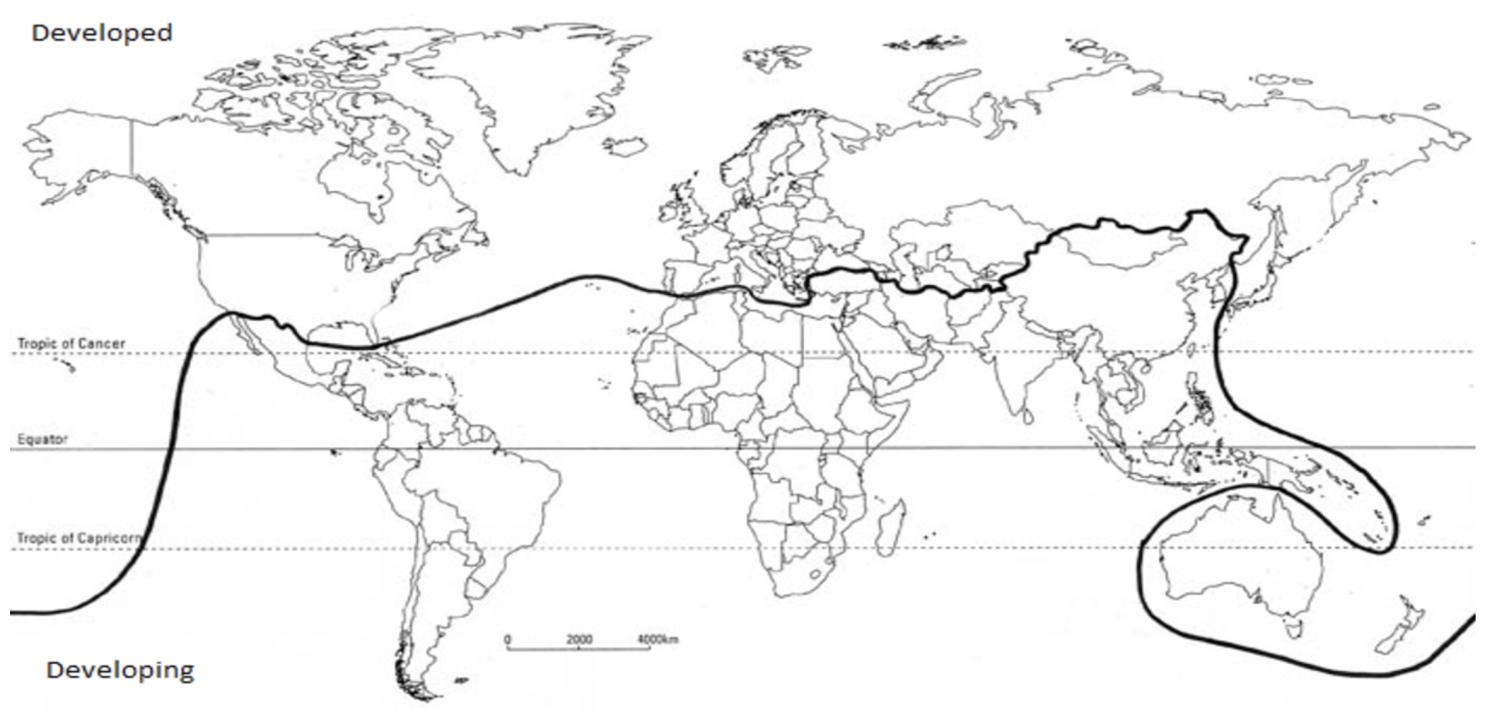

I admit that lumping the world together in two blocks may appear old-fashioned. The idea of juxtaposing the North versus the South goes back to 1980, when the Brandt Report published the famous map shown in Figure 2. How useful is ‘the South’ as an analytical category given its enormous historical diversity in populations, cultures, states, and institutions? I argue that taking the South as a world on its own is defendable, if one allows for hybrid cases (e.g. Japan, Turkey) and is willing to accept the notion of the ‘quadruple challenge’. The quadruple challenge refers to the idea that virtually all Southern states had (or have) to, simultaneously, grapple with the questions of:

- How to catch-up with technology leaders in the West while being at a considerable distance from the frontier.

- How to overcome the variegated legacies of externally imposed institutions (colonialism) or extended phases of limited state autonomy as a result of imperialist and neo-colonialist pressures.

- How to mediate the forces of accelerated globalisation, in particular the volatility of world commodity markets and rising capital flows in the context of their distance to global productivity frontiers.

- How to deal with increasing constraints on cross-border mobility of labour in the context of heightened environmental pressures (the Anthropocene) including climate change.

If these binding elements suffice as a binding core of similarities, then the diversity in local institutions, geographies and colonial trajectories can provide ample material for analysing how these threads intertwine and have led to strongly divergent post-colonial development paths.

Figure 2 The Brandt line

Source: Brandt et al. (1980, p. 31-32) and front cover.

Leading questions

There are numerous big questions that can inspire a South-South divergence research agenda. My paper elaborates three of these. First, what explains the limited spread of the developmental state as it emerged in Eastern Asia, and how can other types of political-economic regimes be qualified? This question has been hitherto been mainly of interest to political scientists. Historians can contribute much to these debates by bringing in deeper time scales, diachronic comparative lenses, and more dynamic conceptions of colonial institutional development. Second, why is development clustered in space and time? Is it nature (geography, agrarian structures, deep-seated cultures) or should we focus on nurture: how regional processes of integration and disintegration have taken shape in Latin America, sub-Sahara Africa, the Middle East or Southeast Asia? Third, can the whole world be developed? To what extent do the newly industrialising economies of Asia jeopardise the opportunities of African economies to conquer new niches in world markets? How does the rising pressure and rising prices of scarce raw materials draw mining economies deeper into their paths of natural resource exploitation? These three questions are obviously not exhaustive, but they are all relevant for economic policymaking in the Global South.

In sum, my paper offers a plea to integrate the global South in the historiography of global economic development on its own terms, and to rethink, how new comparative horizons can open up to move the agenda away from the old question how the West got rich or weird (Henrich 2020), and to the new question why modern capacities to enhance human welfare have so far spread so unevenly across the globe.

It is obvious that new ways of understanding the world need to be developed, but we should not forget that the old ways of thinking still dominate the political discourse that shapes our reality.

Just as an example, take a close look at “Figure 2 The Brandt Line”.

(Source: Brandt et al. (1980, pp. 31-32) and front cover)

The Brandt Line is superimposed on a more modern political map (e.g. easily visible in the area of the former Soviet Union).