![]() ,

,

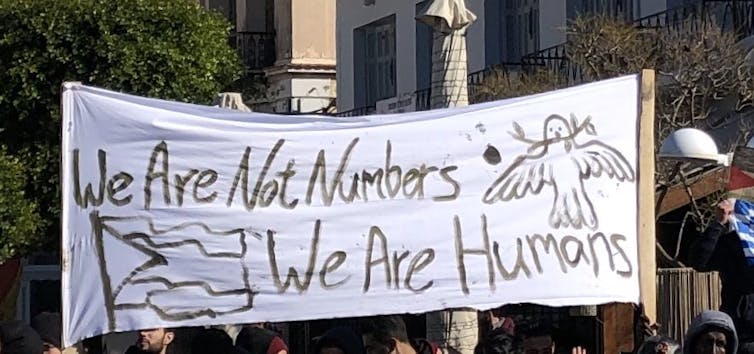

Samos Volunteers

Gemma Bird, University of Liverpool and Amanda Russell Beattie, Aston University

As winter took its toll in January on the Aegean island of Samos, the refugee population stuck there have held peaceful protests against their conditions. But tensions are rising.

The weather on Samos, a Greek island off the Turkish coast, is chaotic and ever changing. When we were there in July 2018, we experienced temperatures in the high 30s with limited protection from the sun and the heat. Now, the winter weather alternates from freezing cold, to torrential rain, to thunderstorms – all in the same day. The weather is not a problem that can be solved for the refugees living here, but the international response to it can, and should be improved.

We have returned to the island as part of our ongoing research into the nature of support provided to the refugee population – which has fluctuated over the past six months with estimates ranging between 4,000 and 5,000 people, depending on who you speak to. The island’s refugee camp is located on the boundaries of the town of Vathy, which has an estimated population of 5,575 people.

The refugee reception centre is run by the Greek Reception and Identification Service and has a capacity of 700 people. But as the number of refugees has rapidly increased, the majority of people now live outside of its fences. They are often a 15 minute walk from toilets or showers – the conditions of which are getting worse – and living in tents that are, in many cases, damaged and incapable of surviving the conditions, in an area referred to as the “jungle”.

Dangerous conditions

Like the main reception centre, the “jungle” is built on a steep muddy hill, which becomes even more muddy and dangerous when it rains and provides very little protection from the elements. Our ongoing research reveals that people struggle to sleep in these conditions, they are cold and wet, or wake up to find rats in their tents. There are not enough ponchos on the island, nor are there enough shoes and socks and as a result people continue to get sick. In January, a bout of the flu was going around the island, most likely a result of the conditions.

Voluntary organisations are working hard to respond to the conditions. Constantly battling one crisis after another, organisations such as Samos Volunteers provide a space for classes, a laundry service, as well as a centre that is warm and dry with a constant supply of tea. Up until now the international response has been sadly lacking. But more NGOs are now coming to the island, and we know of three that set up on the island in January.

Gemma Bird.

NGO workers have confirmed to us that they have supported refugees through the asylum process for up to 18 months. People have to wait for a response from the Greek Asylum Service to their asylum claim – without which they can’t leave the island. Some have had meetings scheduled and then cancelled with little warning or justification.

The logic of the asylum process, of who is and is not vulnerable, who will and will not be transferred and why, is hard for people to comprehend. Then, when travel off the island is permitted, our interviewees have told us of people who have been moved to the mainland and housed in isolated areas with limited connections to support networks.

Endless queues

Life on the island is one queue after another. Everyone has access to three meals a day, if they choose. They must queue for the food, sometimes for up to five hours for each meal. Unaccompanied minors are exempt from this as their meals are provided first. But, in our research interviews, we’ve been told that minors have been injured during this process leading one local NGO, Still I Rise, to offer breakfast and lunch to the children who attend their school.

We’ve also been told by our interviewees of the poor variety of food, with one person suggesting dinner is always potatoes. As a result, there is a lot of untouched food littering the “jungle” outside the camp, leading to further risks of rats and disease.

Gemma Bird

People also have to queue to use the showers and the bathrooms. And queue again to have an asylum meeting, or get onto a waiting list for legal guidance, or on the waiting list for children’s classes, or to access laundry facilities.

Not only could the international community do more to improve the procedures governing asylum and transfer, more also needs to be done to improve the conditions and safety of the reception centre itself, or find an alternative with indoor space, electricity and protection from the elements. The current conditions in “the jungle” are dangerous, and our interviewees have told us of experiences of gender-based violence. Our interviews revealed how they rely on plastic bottles as an alternative to the toilets, which are not only broken, but are dangerous for women and children, especially after dark.

To respond to these conditions, more conversations are needed between the reception centre and the third party organisations supporting refugees. Greater transparency on behalf of the Greek authorities would enable international organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières to provide much needed support to the population within the reception centres, not only on Samos but in each of the four other refugee hot spots on Lesvos, Chios, Kos and Chiros.

In Moria, on Lesvos, the largest reception centre in the Aegean islands, a man was reportedly found dead. An urgent response is needed both there and on Samos before more tragedy strikes the Aegean islands and more families and communities mourn their losses.

Gemma Bird, Lecturer in Politics and International Relations, University of Liverpool and Amanda Russell Beattie, Lecturer in Politics and International Relations, Fellow The Aston Centre for Europe, Aston University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Be the first to comment