On International Women’s Day, the Gig Economy Project speaks to Professor Al James about his research on the experience of female workers in the online gig economy. Interview available as a podcast and in text form.

THE online, desk-based gig economy, sometimes known as ‘cloudwork’ or ‘crowdwork’, has been growing rapidly in recent years. Everything from transcriptions to legal services can be bought by clients on digital labour platforms like freelancer.com from over 150 million gig workers anywhere in the world.

Cloudwork has been touted as a gender-inclusive form of labour which eliminates gender biases and gives women the freedom to live the working lives that suits them. Upwork promotes its platform as being “for a new generation of women” who can build “careers that lead to both financial and personal freedom”. Academic studies have talked up cloudwork’s potential to “help women sidestep traditional barriers”.

Al James, professor of Economic Geography at Newcastle University, has a more critical view of the gendered aspects of digital labour. For the last half-decade he has been interviewing female online gig workers in the UK to find out why they enter this economy and what their experience of it is. He summarises many of his findings on his research project website, Gendered Digital Labour.

In this podcast, the Gig Economy Project speaks to James about his recently published paper, “Women in the gig economy: Feminising ‘digital labour’”.

We discuss:

01:00: What motivates James’ research?

03:47: What do female online gig workers have in common?

10:28: The discourse about online gig work versus the reality

22:53: Gendered exploitation and abuse on online digital labour platforms

34:13: Platform care work

42:33: Lack of feminist perspectives in academic research on the platform economy

AN ABBREVIATED TEXT VERSION OF THIS INTERVIEW IS ALSO AVAILABLE BELOW

Gig Economy Project: Let’s start off by talking about your motivations. Why is it you’re interested in the topic of of gendered digital labour?

Al James: I think if you look at a lot of the platform labour research, women are pretty much invisible. More generally, it tends to be that our understanding of how platforms function, how that work is experienced, that tends to come from the experiences of men in very visible public-facing platforms.

You saw it through Covid. The kinds of gig workers who are visible to members of the public tended to be on-demand service food transport. The platforms in which women are demographically more present tend to be platforms behind closed doors, domestic spaces, and they are invisible to the public and appear to be invisible in the academic literature as well.

You can give the benefit of the doubt to academics and say, well, perhaps they’re looking at the male-dominated parts of the gig economy. But when you look at research on platforms that are female-dominated and you’re still seeing a lack of engagement with women in the research over what’s happening, it becomes an issue.

There is a long standing critique in feminist economics that says we’ve only ever understood how economies function through this assumed male lens. Women tend to drop out of the picture, and the platform economy is just the latest version of this.

From a personal perspective, the work I was doing previously was looking at people’s abilities to juggle family unpaid work in big corporates. So I was looking at IT companies in Dublin and Cambridge. What I saw towards the end of that project, which was about 10 years worth of work, was that women were increasingly quitting firms with poor family friendly working provision. They were either moving to firms with better provision or else quitting the sector completely and going self-employed. A lot of them were turning towards these platforms. I was seeing this in about 2015 and 2016.

So I have come into the project in two ways. First, as a critique of the mainstream research agenda. Secondly, based on what I’ve been doing before.

GEP: Your paper, “Women in the gig economy: Feminising ‘digital labour’”, was in the top five most read papers in the Work in the Global Economy Journal in 2022. It’s based on interviews with 49 women in the UK who use 24 different online digital labour platforms (including PeoplePerHour, Upwork, TaskRabbit, and Freelancer). Can you tell us a bit about who these women are first of all? What sort of online gig work do they do, how much do they earn, what’s their family situation, that sort of thing?

Al James: You are talking about a middle class cohort of women. Most of them have male partners who are in work earning full time outside the home. Some of them are paired off with other freelancers, but that tends to be less common. They are all UK-based and tend to be graduates. So these are crowdwork platforms where they’re providing white collar service-based tasks. What you see is a very strong overlap between the kind of work these women were doing before having kids, and what they are offering now to the platforms.

You can can hire them by the hour or by the project. Many of them will list their hourly pay at around the £20-25 mark. They’re offering work like back office support, copyrighting, web media management, web-based research, social media, etc. It’s a pretty diverse set of offerings. But what unifies it all is that it is desk based, usually from home, although some them are working in jungle gyms, from their cars, and from relatives houses.

It’s a set of tasks that are quite different from the stuff you see on Amazon Mechanical Turk, which is clickwork, where you do thousands of little tasks per day. The women I spoke to are booked in for several hours at a time, or on a longer task that will take several hours.

It’s women who have taken a pause from full-time employment to juggle paid work around childcare. Most of them have majority responsibility for childcare. Most of them have young kids who are preschool age. But you do have a number of women who are single mothers who are grappling with that, and have experienced difficulties previously of trying to slot into a 9 to 5 routine and corporate expectations around face time and and commuting into an office. This research was pre-Covid remember, when the kind of constraints on home working were quite strong.

Most of them are earning between £500 and, in some cases, £2000 a month. In some cases that’s the entire household income, in others it’s contributing around half the income. The vast majority are white women from graduate backgrounds. There are a number of migrant women, predominantly in London, who cropped up in subsequent interviews when I re-visited these workers post-Covid, from Eastern Europe, Africa and Southeast Asia, who are using these platforms because they have a lower barrier to entry than the formal labour market. In some cases it allows them to build up a work history that when they move back home in a few years they can take that with them.

The predominant construction of this work within a lot of the platform literature, certainly around food delivery and transport, is that it’s pretty poorly paid. I’d say that’s not inconsistent with many experiences of the women I’ve spoken to, but there are a few who are earning a very decent living off the back of these platforms, because essentially they have built up their ratings. They’re several years in and they’ve got a very clear work history. A set of reviews, a set of feedbacks that are very positive, and that’s positioning them within the algorithm so that they can then get subsequent work. They’re building up repeat clients, and in some cases they’re taking those clients off-platform, which then increases their income again because they remove the platform fee. It’s something the platforms aren’t happy with, but it does happen.

For others, it’s pretty exploitative. They feel trapped, particularly in the context of Covid, many of them are keen to go back to formal employment once their child goes back into formal schooling, or starts formal school.

GEP: One of the interesting things in your paper was the push and pull factors to entering online gig walk for women. You show that those factors are quite-gender based.

Al James: The dominant discourse around this type of platform work is that it is more involved, more complex, better rewarded. The discourse that you get from many platform managers, policymakers, is that this is enabling new forms of online entrepreneurship. That it’s a big, positive step for women. That, in theory, because they’re competing on these platforms through this anonymous avatar behind an image of their choosing, they can be who they want to be, those old structural inequalities that put women at a disadvantage in formal labour markets are gone. These platforms are supposed to be side-stepping all of that. In theory you can go online and you can advance. And these platform CEOs are telling us that they’re honoured to be helping women make these advances.

What you quickly find in the research that has been done is that it’s a nonsense. Firstly, because the reasons women are going into these platforms are far from positive. It’s actually quite a negative push from formal markets. But secondly, once they are on the platform, actually those inequalities are being reproduced online digitally.

Who I’ve spoken to, many had been looking for family friendly working provision from their previous employer. What you find is a lot of these firms are not convinced of the business case to enable this. So these are things like flexible working, working from home, employer assistance with child care, term time only working, job share; there’s a whole range of these things and provision tends to be quite limited. They tend to offer flex time because it’s cheap to implement, but some of those more expensive options are much more elusive.

A lot of employers, once they hit an economic downturn, will pull a lot of that provision because they see it as expensive and an administrative headache, as something that unfairly privileges a small minority of their workforce. So you’ll see a lot of the provision on paper is not often matched by line manager support.

These women turn to platforms because they were denied a flexible working request. They had hassle from their line manager because of juggling paid work with childcare. They were seen as leaving too early; leaving at 5pm was seen as non-committed. Presentees and cultures where you are expected to be the last one there, and if you weren’t you were frowned upon.

Some of the women were actually laid off, for instance during pregnancy or after returning from maternity leave. Some of this is pretty offensive. So they are turning to platforms due to the low barriers to entry and as a means of working from home, cutting out the commute, taking a hit to the income but essentially keeping your CV work history live during those years outside of the formal labour market. The motivations are rarely positive.

GEP: One of the things that was really curious in the paper is that the flexibility that these platforms tout as one of the main gains of online digital work is actually reinforcing traditional gender roles.

Al James: Flexibility is a pretty ambiguous term. It is flexibility at the level of the firm. What it means for workers is that they are working longer, working harder, working less predictably, often on a schedule that varies week on week, day by day.

The whole history of work-family balance provision amongst employers, there was always this assumption that women will assume the majority responsibility for childcare and the whole government and employer perspective was about how you enable that.

In the UK, we don’t legislate, because that’s interfering in firms’ right to manage. The onus is very much on the individual worker. If you have a problem with your work-life balance, that’s on you as the individual. That’s what you see within the big firms: ‘it’s up to you.’

That approach is being shifted onto the platforms. It goes like this: ‘You failed in the formal labour market, then you moved to a platform. We’re offering you all these new provisions, and it’s still not working. Well, that must be on you, then.’

So it’s taking something we know is problematic in the long standing provision of family friendly working, and it’s inserting it into these new platforms. And in many ways, rather than offering a means out, it’s simply reinforcing the same problem.

Many of these women are critical of these platforms. They say: ‘These platforms aren’t doing this as an altruistic intervention to help women with kids. They’re doing it because it pays them to do so.’

Platforms are making a fortune off the back of this. They take a pretty hefty fee from the client and the worker. So something like Upwork will take a 20% cut. There’s often a whole series of additional fees. So if a job is listed at £30 an hour, often those workers see a lot less. If you think about what’s pushing many women to enter that workforce, they’re profiting off the back of piss-poor childcare provision in the mainstream economy.

Anne Marie Slaughter is a US based commentator. She talks about online platforms as “a godsend” for women, because they enable them to be the kind of parents that they want to be whilst staying in the game. I used Slaughter’s quote in the interviews, and I’ve engaged with over 100 women now over the last 4-5 years who are using these platforms, and it’s rare that you get support for Slaughter’s quote.

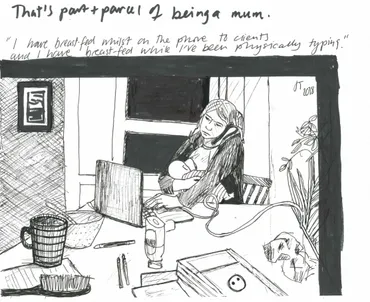

Because it’s not easy work. What flexibility means for a lot of these workers is often working late at night once the kids are in bed. It’s often working weekends. It’s doing tag-team childcare with your partner.

Often these online gigs require a level of real time interaction. Clients are quite demanding, there’s an assumption of a 24/7 service provision. The flexibility on offer is actually quite inflexible. It’s flexible at level of the buyer. But at the level of the seller, you know the pain that’s involved for many of these women to provide that service within the time that’s allocated, it’s difficult.

Many of these jobs are under-specified, so once once they are listed online, and you bid for them, you offer a proposal, and on once you are successful and have got that job allocated to you, the job itself changes. Often it expands. The number of instances I’ve had of people saying: ‘This job, I could work on it for seven days straight without sleeping, and I still wouldn’t have finished it.’ Many of these buyers are deliberately downplaying the amount of work involved, which only becomes clear once you’ve signed up to it.

GEP: That fits in again to the gendered aspect of it doesn’t it, because one of the selling points of these platforms is that it eliminates gender bias, but what you show is that the gendered constraints on being successful in this online gig world are quite substantial. In many ways it is just a digital version of the gender biases people experience in the offline economy.

Al James: That’s the core tension. They’re selling these things as more progressive, giving women more options. But when you look at the ways which the bidding process works, the gigs that tend to pay better have very tight turnarounds. Often it’s over a weekend, which many women simply can’t do. Many of them will not bid on certain jobs because of the constraints of childcare.

Essentially what you’re finding is these platforms that pitch themselves as inclusive – gender inclusive, socially inclusive – it says nothing about the terms on which you are being included. The main takeaway from my paper is that if you’re a woman with kids your ability to compete on these platforms is constrained relative to other workers who don’t have childcare commitments and other workers who don’t have a female identity.

The platforms have clamped down on being anonymous on these platforms, they expect a headshot. They expect consistency between your profile name and your email and your personal details. Many workers deliberately list their childcare commitments in the profile, so that clients are aware of this before they are hired.

Across the board, women tend to get paid less on these platforms than male workers with similar work histories. There are frequent incidences of wage theft where they are not paid at all. You might be hired to do a piece of work and they say: ‘We need a free trial before we’ll take you on’. So they are asked to do a translation, or to do a piece of coding, or a piece of web research. Then the client will say: ‘Sorry it wasn’t good enough, we’re not hiring you.’ But they’ve got the piece of work. Many people I spoke to said: ‘Well, I’ve seen that work used online. I was told it wasn’t good enough. I wasn’t paid for it.’ It’s effectively wage theft.

The thing that effectively enables you to survive and thrive on these platforms is that you need a very positive set of frequent client feedbacks. That’s what makes you visible in the algorithm. In order to get jobs coming to you down the line, you have to build up a profile, it’s like cultural capital within the platform. Many women will deliberately not invoice a client who’s unhappy, because it means the mechanism through which the client can leave negative feedback is gone. So they take that short term pay hit in some instances, you know we’re talking £300-500. They’re willing forego that short term pay hit because they don’t want the longer term hit to their profile.

It’s supposed to be gender progressive, but most women will argue that they’ve never been

subject to that kind of abuse from a female client. It’s always a male client, and the assumption is that if you’re a female platform worker, you’re not going to put up as much of a fight, or that you can be bullied.

This connects to other forms of abuse. There are things like clients assuming this is an extension of Tinder: making comments about someone’s profile image, for example. Some women being hassled by guys who have basically got hold of the contact Information for the job, going off-platform and hassling people directly to their Facebook profile or through their other social media profiles, to the point where they have to block them on multiple channels. In some cases they are worried that these guys are going to turn up at their house, because they have those details.

The problem is that you have a very strong policing by the platforms of the workers. You don’t have the same level of policing for the clients. You can essentially set up a profile, be pretty abusive, and if the platform is to shut that account down you can set up a new profile pretty much overnight. It’s very easy to do that. Platforms aren’t really tracking repeat offenders. Forms of permanent exclusion don’t really exist.

GEP: You say in the report that the “extreme isolation” of the job combined with a lack of workers’ rights means women can have the feeling it is more dangerous than a traditional workspace in terms of health & safety.

Al James: When you are self employed, you don’t have a job contract, and you are subject to a user agreement which in some cases is 24 pages long. You have no line manager. You have no HR Manager. You have no pension. You have no sick pay. You have no maternity pay. You have no sick leave. You have no holiday pay. Many women say: ‘I’m willing to accept all that, as long as the opportunities for paid work on the platform offset that’. But when the level of abuse means that the structures the platform does have in place to protect workers who are exposed are failing, then they say: ‘What am I paying all these fees for?’

So if you’re abused by a client on one of these platforms, as many instances I’ve come across, the platform help desk is basically outsourced. The Helpdesk works as a series of tasks that are put through the same platform. Your issue is being dealt with by another freelancer, so often there is a time delay in responding, and often the ability to act is minimal.

And it’s not uncommon, I’ve found multiple instances of this in a very small cohort. What you are beginning to see is patterns of mutual support among some of these freelancers, independent of the platform. Some of them are building online networks, some labour unions are beginning to pick up on this.

There is work on gender based cyber violence that colleagues have pushed me towards. I’m trying to connect this with these instances on the platforms. There is a bigger research agenda around this.

GEP: Let’s talk a little bit about other parts of the gig economy. One important area is platform care – cleaning work and home care work – which like online gig work has been presented by the platforms as a godsend for women because the ratings systems mean potentially more transparency is brought to a form of work which has historically been prone to abuse because it takes place in people’s homes and tends to be very low-paid and disproportionately female migrant workers. What can you tell us about platform care?

Al James: The work I’ve researched is is effectively remote. You never actually meet the client in person. Care work takes on a new dimension, because you’re physically entering someone’s house. So where it’s emerged in my own research is women who used to do that kind of work and then because of Covid have pulled back from it, and moved into desk-based crowdwork. The vulnerabilities of going into someone’s home became amplified.

The platforms present what they are doing as trying to formalise this work. In India that is very much the pitch: ‘We are taking something that’s very informal, and the platforms are formalising this for the better.’ However, there’s evidence that what is really happening is they are just shifting how exploitation is done.

It’s a slightly different discourse in the UK. But the times at which clients want you to come into their home are often when they’re physically there, so they can keep an eye on you. That tends to be after their own working day is finished. So effectively what you’re doing is providing reproductive support at the expense of your own. If you’re going to someone’s house from 5-7pm at night in order to help with their meals, cleaning and childcare support, often that’s at the expense of your own.

Ironically, you’re taking something that’s been traditionally devalued in the formal economy – reproductive labour behind closed doors, not done for a wage, not contractualised, appropriately female – and you’re then commercialising it. Women are providing these functions for wealthy people, so there is a kind of class inequality there but also a migrant inequality. There is work being done by colleagues at Queen Mary University in London on migrant workers who are looking after the the children of very well-off middle-class couples in London. Some of that is organised by the platform. Then they’re going home to put their own child to bed over the phone on Skype and on Whatsapp thousands of miles away back home.

GEP: An important aspect of your paper, which you’ve already mentioned, is a critique of academic research on the gig economy. You say that “women gig workers remain empirically and analytically marginalised, and the gendered dimensions of gig work heavily under-researched”. Probably it’s also true to say that in the media, women gig workers are also under-reported on and the voices of female gig workers are heard significantly less than males. What do you put this down to, is this just typical sexism or is there something particular to the gig economy which is driving this? And how do you think this can be addressed, whereby feminist perspectives are included in the debate?

Al James: It is changing. Three years ago, when I started working on that paper, there wasn’t a particularly large research body of work on women platform workers to deal with. I’m now working on the book length treatment of this, and there is a lot more, but still it’s a small minority. I’ve done bibliographic research, and it’s less than 1% of the research on platform labour that is engaging with women.

I don’t think it’s purely an empirical issue. 163 million workers worldwide are using platforms to get paid work. These figures are from the ILO and the Oxford Internet Institute. They also suggest that 39% of those workers are women. So if you applied those two figures together (which the ILO would caution you not to do because of the way they they generated those numbers) it’s about 63 million women worldwide using these platforms for means of income. So the fact that you’re seeing very little research on them can’t be defended on the basis there aren’t many women in the platform economy.

I think this problem has come from the front-runner case that we used to produce that research. Uber was done to death as a research topic. We’ve learned some fascinating stuff about how platform algorithms function and inequalities, what flexibility really look like; it’s amazing research. But it’s come from a platform that’s typically about 70-80% male. Then when we’re talking about what does platform labour look like more generally, we talk about the Uber for care, the Uber for marketing, the Uber for transcription, the Uber for accountancy or or copywriting. Uber becomes this paradigm that we assume other platforms are following in the image of.

Also, I think a lot of the academic community itself, particularly within platform labour, have not come from feminist labour studies. They’ve predominantly come from computer science. They’ve come from studies of internet geographies and digital working that weren’t explicitly coming from a feminist perspective or a family perspective. When I look at those traditions of feminist study for the last five or six decades, there’s not many scholars who have started engaging with platform work from the other direction. I think it’s because it doesn’t look like the kinds of forms of employment that they would traditionally engage with. When you look at all the work-family research, it’s about an employer providing something for an employee. That employee-employer model does not work in the platform economy, it doesn’t have an equivalent. So the kind of concepts we’re using to understand work-family provision in the mainstream literature need a lot of work to make them viable within that that kind of platform world.

I’ve been to platform labour conferences for the last five or six years, the demographic is slowly shifting, but for a long time it was a male research community talking to workers like themselves. I think some of the most vivid examples are coming out now. For instance women gig riders, Deliveroo and others, and the practicalities of juggling female health with doing that kind of work. Many of them are changing their sanitary towels behind bins outside a block of flats because there’s no employer provided provision of toilet facilities. They’re weeing in bottles, they’re getting hassled at pick up; It has overlaps with the kind of harassment i’m seeing in my research, but in that case it’s behind a screen so it’s quite different. I am seeing increasing numbers of Phd students engaging with these kinds of working realities, I think it is shifting.

To sign up to the Gig Economy Project’s weekly newsletter, which provides up-to-date analysis and reports on everything that’s happening in the gig economy in Europe, leave your email here.

Thanks to many generous donors BRAVE NEW EUROPE will be able to continue its work for the rest of 2023 in a reduced form. What we need is a long term solution. So please consider making a monthly recurring donation. It need not be a vast amount as it accumulates in the course of the year. To donate please go to HERE.

Be the first to comment