A new study takes an in-depth look at the platform lobby in Brussels in wake of the Uber Files scandal, finding they are more deeply entrenched than ever

The battle over the EU Platform Work Directive is heating up. With a vote expected in December, both the platform lobby and the trade union and platform workers’ movement are mobilising.

On Tuesday [25 October], the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) will hold a protest alongside Belgian unions outside the European Parliament to demand a “strong” platform work directive, after reports of manoeuvres in both the European Parliament and the European Council to weaken the Commission’s draft directive proposal.

Meanwhile, Uber’s former chief lobbyist in Europe, Mark MacGann, will address the EU Parliament’s Employment Committee on Tuesday. MacGann was the whistleblower behind the ‘Uber Files’ scandal in July, which revealed the massive lobbying spend and multiple dirty tricks of the US ridehail giant, which described itself as “just fucking illegal”.

A report published today shines more light on exactly how the platform lobby in Brussels goes about its business. “Uber Files 2 in Brussels” is published by Observatoire des Multinationales, which – as the name suggests – is a French NGO seeking to shine a light on the realities of corporate power. The study was commission by the Left group in the European Parliament. Read the full report here.

Here’s five things the report teaches us about Brussels’ platform lobby.

1) Lobbying spend has been massively ramped up over recent years

As moves to regulate the gig economy in Europe have become more serious, platforms have ramped up their spending on lobbyists in Brussels. Uber’s spending is currently over €700,000 a year, a 1400% rise since 2014. Finnish delivery platform Wolt had one lobbyist in Brussels in 2020 – they now have eight. Bolt have doubled their lobbyists in three years from three to six.

2) The platform lobby have stepped up their efforts since the draft Platform Work Directive was published

The platform lobby battled hard to prevent any presumption of employment in the draft European Commission directive in December, but they failed, and were angry about it. But that doesn’t mean they just packed up and went home.

Instead, they “changed their target” from the Commission to the EU Council (the heads of member-states) and EU Parliament, which both have to sign-off on the Directive before it can become law, and can amend it before doing so.

“From January 2022, the platforms begun to arrange meetings with national civil servants representing the Member States in the Council,” the report states. “Thanks to its transparency policy, it’s possible to know the number of times the Dutch government met with lobbies in Brussels. To discuss the directive to improve working conditions of platforms, representatives of the Netherlands in the Council met Wolt three times, Deliveroo twice, and Move EU and Bolt once between January and May 2022. A total of seven meetings in five months.”

They have also targeted MEPs in the EU Parliament, and have used all the levers they have available to them to do so. For instance “in June 2022, a coalition of MEPs signed an op-ed in Politico (the daily newspaper of European decision-makers), arguing against an employee status for platform workers,” the report states. “Choosing Politico raises questions, as the group that owns Politico Europe, Axel Springer, discreetly invested 5 million euros in Uber in 2017. Publishing an op-ed that aims to reduce Uber’s labour costs is a conflict of interest when Uber represents a portion of its income.”

Finally, Uber has also brought its big guns to Brussels, moving the company’s chief lobbyist in Paris to Brussels in April 2022. “The ‘Uber Files’ revealed Uber’s declaration that it could count on the support of France in the European Council, particularly of Prime Minister Elisabeth Borne and Minister Delegate for Transport Clément Beaune,” the report finds.

3) The platform lobbying web is broader and deeper than you might think

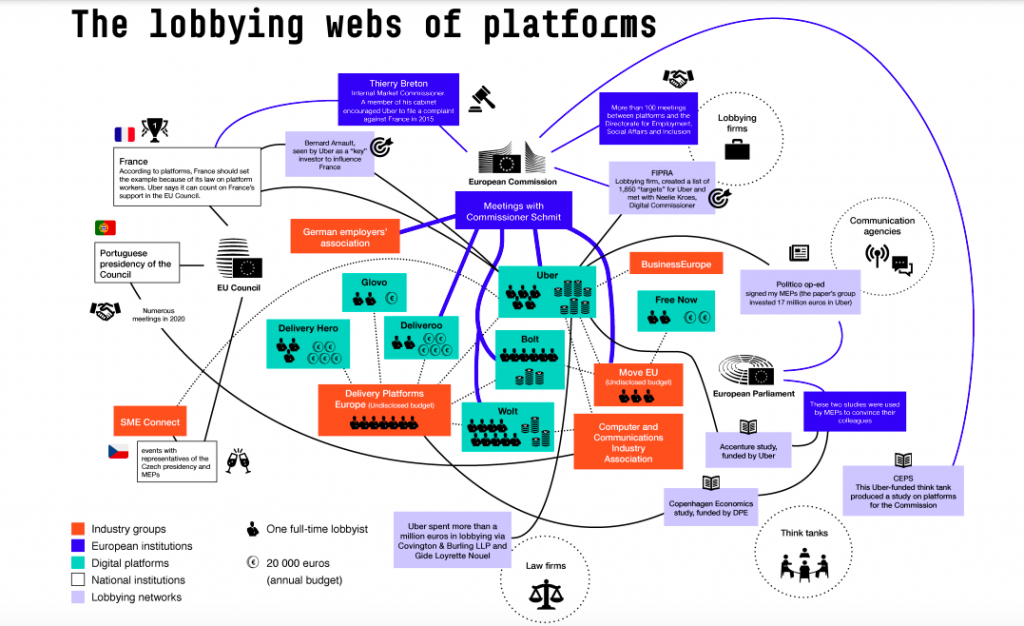

The study examines the wide variety of means which the platform lobby has at its disposal to pursue its interests both directly and indirectly, summarised in this image below.

Some key elements to pick out include the use of consultancy firms to provide another door into the EU. For example: “Bolt spent between 100,000 and 200,000 euros in 2020 to pay for the consultancy and communication services of Portland, an agency founded in 2000 by Peter Guilford, a former spokesman for the Commission. It was through Portland, for example, that Bolt obtained a meeting with the cabinet of the European Commissioner for the Internal Market, Thierry Breton, on September 7, 2021.”

Also, broader business associations which the platforms are part of act as an extension of their lobbying power. Business Europe, for example, is the largest lobbyist in Brussels and Uber is on its advisory structures. “Business Europe enjoys privileged access to the European Commission, in part thanks to annual Commission meetings bringing together European Commissioners and the most influential CEOs,” the report states.

Finally, the platform lobby fund think-tanks which often portray their research as independent, and are often treated by the EU machinery as if they were independent. For instance, Uber is a member of the CEPS think-tank, which was “commissioned to write a study on digital platforms – and their working conditions specifically – by the European Commission in June 2021.”

4) The platform lobby will diversify its tactics depending on the balance of forces

For the platform lobby, the tactics they apply depend on the balance of forces at any given point in time. If they are losing (as they have been at certain stages with the EU Platform Work Directive), they can quickly turn nasty, seeking to delegitimise opponents, undermine the legislative process, publish fantastical figures about potential job losses based on dodgy studies, and threaten legal action. Of course, if all that doesn’t work, they can also seek to make the legislation unworkable even when it is introduced (see the Spanish ‘Rider’s Law’ for a very current example).

For example, in November last year Bolt argued “that drafting a law on labour matters was beyond the Commission’s Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion Directorate’s legal competence,” the report states. In September, Move EU (a Brussels lobby group consisting of Bolt, Uber and Free Now) told the EU Commission that “drivers’ lawsuits targeting platforms were only driven by the plaintiffs’ desire to extort money from the various platforms”.

These platforms have little shame about saying one thing in public and another in private. After Uber and Bolt told the Commission in a lobby meeting that a presumption of employment could see half of all platform work jobs lost – a disaster for platforms if it were to ever occur – Uber’s CEO told investors in a behind closed doors meeting in December 2021 that “the company could continue making profits even if a new law forced Uber to recruit its drivers as employees,” the report finds.

5) Even after Neelie Kroes, the revolving doors between the EU and the platform lobby remain

The Uber Files revealed that Neelie Kroes, the EU Commission’s former Vice-President, had broken EU lobbying rules by lobbying a Dutch minister “to force regulator and police to back off” Uber. The Files show Uber went to great lengths to disguise the extent of the company’s working relationship with Kroes. The outcry over Kroes has forced the EU’s anti-fraud office to open an investigation, but the revolving doors between the platform lobby and the EU does not begin and end with Kroes.

The report states: “Fabrice Comptour, who currently works in the Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton’s office, attended a meeting with Uber in 2015 with Mr Breton’s predecessor, Ms Bienkowska. Mr Comptour and the former Commissioner are said to have inspired, and even encouraged, Uber to file a complaint to the Commission against France, Germany and Spain for restricting Uber’s expansion possibilities. The 2015 meeting will be described as excellent by Uber. Fabrice Comptour is also very close to Emmanuel Macron. Shortly after the launch of Macron’s political party “En Marche!” (now Renaissance), he contributed to internal memos on European defense issues. This is not the only example of political alignment between the Commission and platforms. Bolt CEO Markus Villig sits on the EU Innovation Council. Zuzana Púčiková, director in charge of European policy at Uber, has been appointed a climate ambassador for the European Commission.”

With friends in high places, the platform lobby is unlikely to be panicking any time soon about the prospects for legislative reform hurting its business model.

To sign up to the Gig Economy Project’s weekly newsletter, which provides up-to-date analysis and reports on everything that’s happening in the gig economy in Europe, leave your email here.

Support us and become part of a media that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over.

Be the first to comment