John Weeks is right: Either we do this together or we shall fail. He is also correct in citing that the climate disaster can only be halted by changing our whole economic system: the capitalist prerequistie of growth and and exploitation.

John Weeks is PEF Council Coordinator, Professor Emeritus, School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London, and author of ‘Economics of the 1%: How mainstream economics serves the rich, obscures reality and distorts policy’, Anthem Press.

A central characteristic of neo-liberal ideology is to render contentious public policy issues apolitical. As I show in my forthcoming book, Debt Delusion (Chapters 6 and 7), misrepresenting economic policies as apolitical was central to the construction of the reactionary neoliberal agenda. While the neoliberal grip has weakened, especially over economic policy in Britain, it remains powerful. An outstanding example is the UK debate over membership in the European Union, which the centre presents as a choice between civilization and chaos.

Analogously, the mainstream media including the Guardian newspaper has sought to frame environmental protection in a non-political manner. This de-politicising of environmental debate shares some characteristics with the degeneration of the UK debate over the European Union. In the case of the environment disaster will be the certain consequence of inadequate action. However, placing the weight of argument on pending disaster which no reasonable person can deny or continence relies on fear to convince people and their elected representatives to act.

Two media-grabbing vehicles for sparking debate demonstrate the apolitical presentation of the very real environment danger, the leap to celebrity status of a Swedish teenager and the direct actions by the Extinction Rebellion. As welcome as participation by youth is, the principle propaganda effect of the former has been to misrepresent environmental policy as reflecting a generational divide. The teenager berated a cross-party group of British parliamentarians for failing her generation, who appeared appropriately chastised.

While legislative action to counter the gathering environmental disaster has been woefully inadequate, attributing failure to generational conflict is empirically and conceptually false. A distinguished role call of “oldsters” lead and are dedicated to achieving effective action on environmental protection in Europe and North America, including major politicans, notably Jeremy Corbyn and Bernie Sanders (sexagenarian and septuagenarian, respectively).

Generational conflict appears as a common argument to de-politicise many major issues, such as wealth concentration. All such arguments share a fundamental flaw, the failure to view humans as living in societies. As should be obvious, in all societies the old were once young and the young will grow old. The idea that society is permanently divided between age groups is a variation on Margaret Thatcher’s infamous assertion that there is no such thing as society.

Nor is it true that environmental issues are more relevant for the young that the old. To the contrary, the immediate health impact of pollution on the elderly is at least as serious as for children and teenagers, with respiratory aliments the most obvious. However, the generation divide serves as a useful function for those who wish to avoid confronting the politics of environmental change.

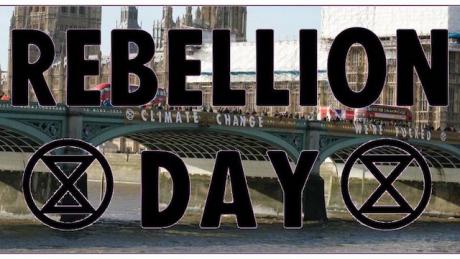

The Extinction Rebellion movement can justifiably claim to be overly political. It applies the principles of Regis Debray’s foquismo to the gathering climate danger. The revolutionary practice of foquismo asserts that the bold public actions of a dedicated few will by demonstrating the weakness of authority inspire insurrection in the population as a whole. Extinction Rebellion blocking London’s Waterloo Bridge had the purpose to “focus” public attention on the urgency for strong action to reverse environmental damage. The effectiveness of foquismo to achieve political change remains an open debate beyond the scope of this article.

The rather trivial generation divide approach to climate politics and the more political foquismo share two important characteristics. First, from my direct observation and a review of photographs on the web, it would appear that both suffer from a lack of ethnic and income diversity. Second, neither stresses capitalism as the driving force of environmental destruction. Both carry major political implications. The first results in emphasis on issues important to middle classes, even though a 2018 report by the US government concluded that poor communities systematically suffered more from environment damage.

The omission of the importance of capitalism is extremely serious, because capital’s inherent tendency to expand continuously drives the deterioration of the global environment. Competition for lower costs and larger market shares drive the tendency among capitalist producers to expand (elaborated in my 2010 book Capital, Exploitation and Economic Crises, Chapters 8 & 10). With typical clarity, Mar wrote,

Capitalist production…disturbs the metabolic interaction between man and the earth…Capitalist production, therefore, only develops the technique and the degree of combination of the social process of production by simultaneously undermining the original sources of all wealth—the soil and the worker. [Quoted in article by Oleg Komlik]

We can pursue Marx’s argument further to include the polluting of the atmosphere and despoiling of the oceans.

Achieving a sustainable environment in which humanity thrives requires the radical transformation of society to what some have named “post capitalism”. That transformation involves the strict regulation of capitalism. The political progress to achieve a regulated, sustainable capitalism will directly confront the power of capital; i.e., it will be a class struggle. At the risk of appearing dogmatic, I argue that success in that struggle requires a progressive movement based in the working class, such as the UK Labour Party (and its manifesto and Green New Deal) and the US presidential campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren.

In the Heavenly Paradise it may well be that a child shall lead them (Isaiah 11:6) but not in the worldly reality of avoiding environmental disaster.

Be the first to comment