The European Central Bank’s new Transmission Protection Instrument gives it even more power over Eurozone member-states

Cross-posted from the Positive Money Europe blog

What does fragmentation in the Eurozone mean?

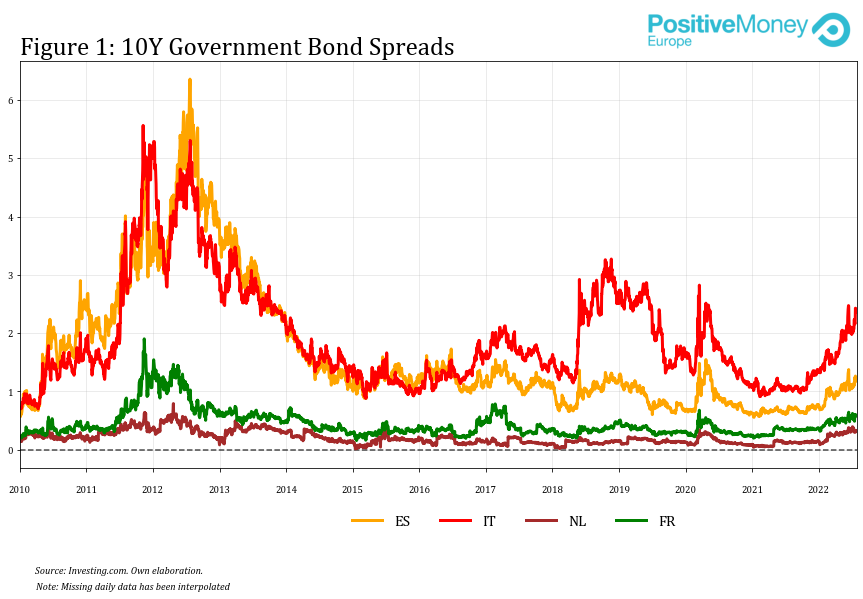

Fragmentation is the divergent movement of government bond rates across the Eurozone, the so-called “spreads” (Figure 1).

Government bond rates reflect the cost of borrowing for governments in the Eurozone and greatly influence wider financing conditions in the country. If government bond rates rise, this is problematic for two reasons: First, they make public and private investments more costly. This happens at a time when investment needs are high, particularly to recover from the pandemic and to speed up the climate transition. High borrowing costs will lead to foregone investments, and hence declining growth. Second, it causes debt-servicing costs to rise. Both weaker growth and higher interest payments will lead to a higher debt-to-GDP ratio, which will itself raise interest payments once again, creating a vicious cycle. Without strong outside intervention, it is almost impossible to break out of this negative loop.

The divergence in government bond rates, the so-called “spreads”, is measured with respect to the benchmark of the German government bond (Figure 1). For example, if the Italian government bond rate rises by 3 percentage points while the German Bund increases by only 0.5 percentage points, the spread of the Italian bond is said to have increased by 2.5 points.

The issue of widening spreads reoccurs

When the ECB signalled an end to its 7-year-long quantitative easing programme to address high inflation, Italian government bond rates started to increase rapidly, diverging greatly from the German government bond rate. The situation became so worrying that the ECB convened for an emergency meeting on 15 June and started internally working on a tool that could address this fragmentation risk.

The ECB must act on such fragmentation risks because if it doesn’t, disorderly market behaviour might further drive government bond rates apart which would destroy the singleness of the ECB’s monetary policy. For example: If the government bond rate in Italy is much higher than the government bond rate in Germany, financial conditions will be tighter in Italy, which means that aggregate demand in the economy is weakened in Italy in comparison to Germany, leading to different magnitudes of (dis)inflationary pressure. The result is that it will be harder for the ECB to maintain price stability across the Eurozone.

What is the new “Transmission Protection Instrument”?

On 21 July 2022, faced with widening spreads, the ECB decided to adopt a new tool, the so-called Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI). It involves the ECB buying assets in the countries where financing conditions deteriorate to the extent that the transmission of monetary policy is at risk.

TPI will be enacted depending on a “comprehensive analysis of market and transmission indicators”, whereby the ECB will check whether a rise in government bond rates hampers the transmission of its monetary policy and is not justified by economic fundamentals. Economic fundamentals are a set of macroeconomic variables through which the “health” of an economy is examined, such as GDP growth, debt-to-GDP ratios, and the current account balance. This means that the ECB will enact the TPI when spreads rise due to negative market sentiment, which can trigger the vicious circle described above.

When spreads rise due to such negative market sentiment, the ECB will review whether the candidate country complies with rules and recommendations on government deficit, debt sustainability, macroeconomic imbalances, and structural reforms. This is the criteria that will be used by the ECB in an indicative way and at its own discretion to decide whether a country is eligible for TPI. Therefore, the ECB has substantial discretionary power to decide when and where it enacts this tool, as it decides both if rising spreads are not warranted due to fundamentals and whether the eligibility criteria are met.

The circular reasoning in the TPI activation criteria

Looking at the criteria for activating TPI, there is a clear dilemma: The criteria for activating the TPI are partly affected by the actions of the ECB itself, and specifically by the implementation of the TPI. Both the country eligibility criteria and the commitment to act only on “a deterioration in financing conditions not warranted by country-specific fundamentals” are variables that are inside the ECB’s realm of influence. This is especially so concerning debt sustainability parameters.

The pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) is an excellent example of this. A recent paper published by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) shows how the PEPP, implemented by the ECB during the Covid-19 crisis, had a positive impact on debt sustainability dynamics. Without it, debt would currently be on an unsustainable trajectory.

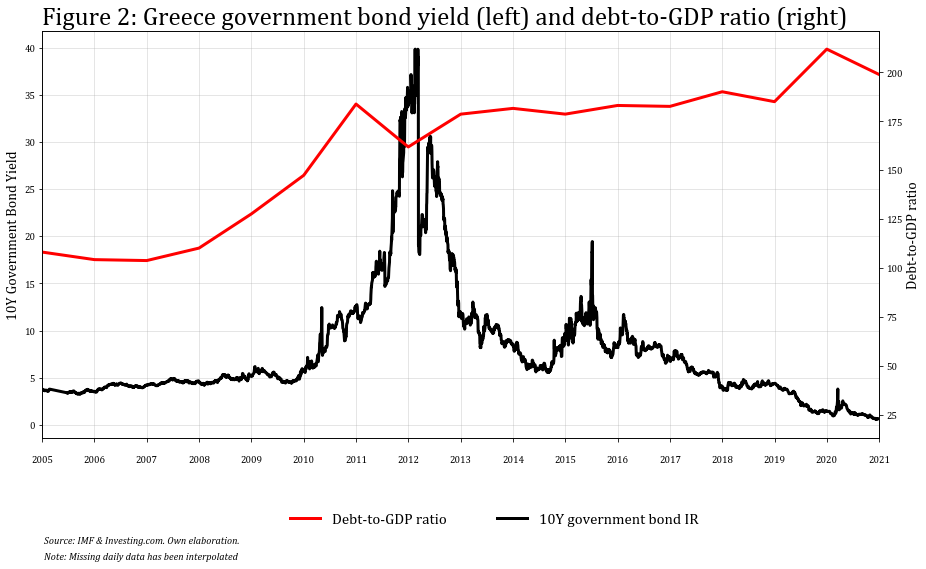

The Greek case is very illustrative. During the Eurozone crisis, Greek public debt was seen as too high by bondholders, increasing the government bond rate. To counteract rising interest payments on government bonds, and being pressured by the core economies and the IMF, the Greek government embarked on an austerity programme, which put a high toll on growth. The latter further worsened the debt-to-GDP ratio. These trends negatively reinforced themselves, as the ECB did not act as a lender of last resort. Two years later, when it decided to do so, the damage had been immense. In the Covid-19 crisis, the situation took a 180-degree turn. Since the ECB acted as lender of last resort for Greek debt through PEPP, the Greek government could respond to the crisis with an expansionary fiscal policy programme. The result has been a quick bounce back of GDP, and hence a falling debt-to-GDP ratio in 2021 (Figure 2).

What this shows is that the ECB has a key role in influencing the criteria for activating the TPI. Ultimately, a Eurozone’s government debt will be sustainable if the ECB decides so.

The eligibility criteria mask the ECB’s discretion

Some commentators have argued that the ECB conditioning the activation of the TPI on criteria set up and monitored by the European Commission and the European Council ultimately puts the power in the hands of the latter. But as the fulfilment of the criteria crucially depends on ECB actions, power arguably remains at the ECB. Hence, as it stands right now, the implied legitimacy from deference to “externally” fulfilled criteria is a farce. The ECB stays in control, and its high discretion in deciding when to activate TPI accounts for that.

The ECB’s discretion is a double-edged sword. It allows the decision-makers in the Governing Council to either abdicate or take responsibility for helping government finances to stay on a sustainable path. Given that the ECB, with the TPI tool, has the power to make or break negative feedback loops, all eyes are on its technocrats to make the right decision.

We shouldn’t rely on the wisdom of ECB decision-makers

From a legitimacy point of view, the discretion that the ECB enjoys is problematic. Legitimacy could be improved by EU member states and institutions reforming the fiscal criteria that TPI references. For example, they should exclude the primary balance for the primary deficit in its criteria, as economists from the think tank “Dezernat für Zukunft” propose. Thereby, a part of the circular reasoning embedded in the criteria for activating TPI would be eliminated such that the criteria become something that governments are able to fulfil more independently from the ECB.

In our view, the ECB should and must backstop sovereign bond markets, and hence it is to be appreciated that its new TPI tool comes close to doing that. But as the consequences of not doing so could be disastrous, more institutional changes, including a reconsideration of the ECB’s mandate, are desirable. For the current juncture, something more modest is important: the ECB administration recognising the power of its policy choices, and acting accordingly. If it does so, TPI will help the project of preserving the euro.

Further readings

De Grauwe, P., & Ji, Y. (2013). Self-fulfilling crises in the Eurozone: An empirical test. Journal of International Money and finance, 34, 15-36.

De Grauwe, P., & Ji, Y. (2022). The fragility of the Eurozone: Has it disappeared?. Journal of International Money and Finance, 120, 102546.

Vernazza, D. R., & Nielsen, E. F. (2015). The damaging bias of sovereign ratings. Economic Notes: Review of Banking, Finance and Monetary Economics, 44(2), 361-408.

Support us and become part of a media that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over.

Be the first to comment