This could be the most significant test of Spain’s fairness as a society.

Koldo Casla is Lecturer at the Human Rights Centre and School of Law, University of Essex, UK

Cross-posted from Open Democracy

Starting last month, Spain has a minimum income scheme in place. Considering some of the international coverage, you would be forgiven for thinking it is some sort of universal basic income. It is not so. It is rather a social assistance programme for the poorest families, similar to the ones existing in other European countries. Households will be allowed to claim between 462 and 1,015 Euro depending on their size and composition. The benefit will be compatible with other sources of income, in which case the amount of the benefit would be lowered accordingly.

It is a very last resort, which, believe it or not, the fourth largest economy in the Euro-area did not have until now, not at least for the whole country, and not one that deserved that name.

If it works well, this initiative has the potential for alleviating the most severe forms of social exclusion. Spain has the dishonour of having one the highest rates of child poverty in the EU: one in four children live below relative poverty in households that get less than 60% of the median income. After a long decade of austerity policies, this is a victory for the left, possibly the most significant one since equal marriage (2005), the social care law (2006) and the historical memory law (2007).

But, as well as a victory, it is also the expression of a huge policy and political failure. Spain’s regions and nationalities have had the power and the responsibility to protect the most vulnerable for more than three decades. However, by and large they have failed to do so, in a systematic breach of the human rights to social security and to an adequate standard of living.

The 1978 Constitution established that social security should be maintained “for all citizens (to) guarantee adequate social assistance and benefits in situations of hardship” (Article 41). Spain does have social security with public pensions, including non-contributory pensions, unemployment protection and other economic benefits for those temporarily unable to work for different reasons. But a lot of people suffer long-term unemployment, work in extremely precarious jobs, or are simply left behind by the system. The Constitution also bestowed on regions and nationalities the power to set up complementary social assistance schemes (Article 148.1.20), and all 17 of them accepted this responsibility in their respective statutes of self-government.

Starting with the Basque Country in 1989 and Andalusia in 1990, each region has created its own system. But there is huge variation between them in terms of coverage, adequacy and conditionality.

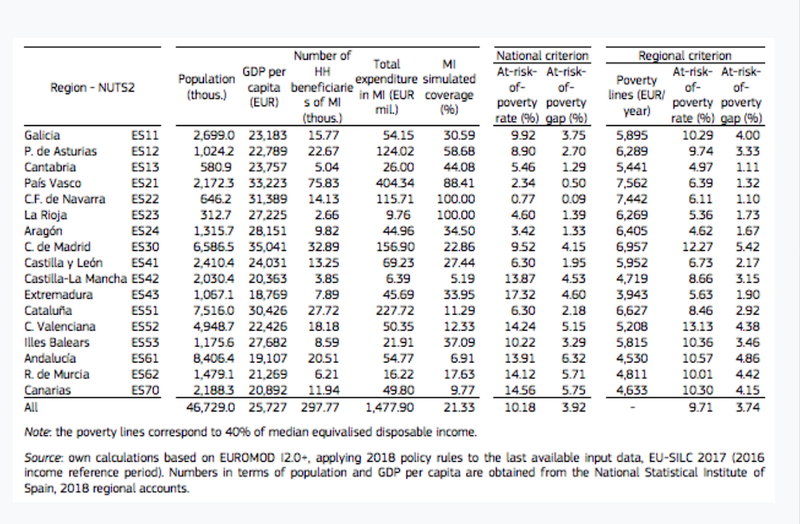

As seen in the table below (based on data from 2018), Madrid and the Basque Country are two of the richest regions, with similar levels of GDP per capita. Yet, despite having one third of Madrid’s population, and half the poverty level (6.4 for 12.3%), the Basque scheme reaches 2.3 times more people and public expenditure is 2.6 times greater. The Basque programme covers 88% of those in greatest need, compared to 23% in the case of Madrid.

With the exception of Navarre, La Rioja and the Basque Country, the vast majority of regions leave out half of the population that meet the economic criteria. The general average is just 21.33%, which means that almost eight in 10 people are unable to get the economic support they need. With just over 8% of the country’s population, nearly 38% of all recipients, living in the Basque Country, Navarra or Asturias, the three regions accumulate 43% of all of Spain’s public spending on minimum income.

The austerity of the 2010s created an ever-greater need for a people’s quantitative easing. However, because of limited resources in some cases, and ideological blindness and lack of interest in others, for three decades the regional public authorities failed to fulfil the right to social assistance recognised in Article 13 of the European Social Charter, leaving millions of people behind.

Looking at the small print

Let us hope Spain’s new minimum income scheme will mark a turning point. For now, it is too early to tell if it will match up to the expectations. A number of issues remain unclear and are concerning.

For example, the coverage is arbitrarily limited to people between 23 and 65 years of age. Public authorities at the central, regional and local levels should urgently develop truly accessible and non-bureaucratic procedures. Considering the digital divide, it is essential to establish a system by which individuals can request this benefit from social services face-to-face. In light of the concerning experiences in other countries, observers must watch out for the possible misuse of sanctions and conditionalities. Just as crucial, existing regional schemes should be retained and developed to complement the new central benefit.

The elephant in the room is that none of this would have happened without Covid-19. But this cannot be a passing whim, nor a PR stunt for the left-leaning coalition government. The right-wing Popular Party and the extreme-right Vox seem very confused. Some of their leaders have spoken against this initiative with hyperbolic references to the nanny-State. However, they did not dare to vote against it when the debate came to Parliament in mid-June.

The real test will come when the flashlights focus on something else. If the practical questions get answered, and if conservatives do not get rid of it when they return to power whenever they do, then we will be able to celebrate this as one of the most important victories of the left.

This could be the most substantial policy for the people at greater risk of harm, disadvantage and poverty. This could be the most significant test of Spain’s fairness as a society.

Be the first to comment