Could a new financial crisis, brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic, lead to Italy’s exit from the eurozone? Lucio Baccaro, Björn Bremer and Erik Neimanns present evidence from a new survey experiment on Italian attitudes toward a European bailout and exit from the euro. They find that a majority of voters would opt to stay in the euro if a bailout did not involve conditionality, but that there would be a majority for leaving if a bailout were contingent on austerity policies.

Covid-19 has increased the risk of a new financial crisis in the eurozone. This time the epicentre would most likely be Italy, where public debt, already very high before the pandemic, nearly reached 160% of GDP in 2020, and growth has stagnated for the past 25 years. If financial markets started to have doubts about the sustainability of Italian debt, they would push the interest rate spread up, and force the Italian government to either ask for a European bailout or exit from the euro.

According to the rules introduced in the first stage of the euro crisis, a country applying for a European Stability Mechanism (ESM) loan has to sign a Memorandum of Understanding committing to austerity and structural reforms. An ESM programme is a prerequisite for Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) by the European Central Bank (ECB), that is, potentially unlimited purchases of government bonds by the central bank.

One of the problems with this crisis resolution strategy is that the austerity measures imposed on crisis countries are highly unpopular and lead to electoral volatility, public protests, and the emergence of anti-system forces. Still, existing research shows that voters in most crisis-ridden countries are unwilling to leave the euro despite the high social costs of austerity. In July 2015, Greek voters rejected the European Union bailout package in a popular referendum, but research shows they still wanted to remain in the common currency. This unwillingness to leave, despite the costs of austerity, strengthened the hand of ‘creditor’ countries and allowed them to shift the burden of adjustment on ‘debtor’ countries during the euro crisis.

A financial crisis in Italy, the third largest economy of the eurozone, would have profound consequences for the euro. Many commentators believe that the euro stands or falls with Italy, and the possibility of exit is far from purely academic. In the wake of the euro crisis, the Five Star Movement (M5S) included the promise of a referendum on the euro in its electoral manifesto of 2014, while the Lega proposed a negotiated exit from the eurozone in its 2018 and 2019 manifestos. Moreover, support for the euro before and after the Covid-19 outbreak was significantly lower in Italy than in almost any other country. Still, we know little about how Italians would weigh the costs and benefits of staying in the euro in case of a financial crisis, and how they would react if a financial bailout was contingent on austerity and structural reforms.

A survey experiment

In a recent study, we presented a large sample of Italians (n = 4,200) with a hypothetical scenario of a Greek-style financial crisis. We ran our survey experiment in October 2019, in the wake of a standoff between the Italian government and the European Commission over the country’s government deficit. We used sample quotas to ensure a representative sample based on age, gender, and economic sector, and survey weights to further correct for deviations in our sample from the true population on other dimensions. However, our results are robust to the use of different types of weights, or no weights.

All respondents read a scenario in which Italy was in the midst of a financial crisis, involving freezing of liquidity provisions by the ECB, a run on banks and capital flight, a rapid increase of risk premia on government bonds, and the inability of the government to meet its financial obligations. Respondents were then told that before accepting a European bailout package, the government wanted to consult its citizens through a referendum, asking whether they wanted to stay in the euro and thus accepted the bailout package, or rejected the bailout package and therefore wanted to exit the euro. Finally, survey participants were asked how they would vote in this hypothetical referendum.

We combined the basic scenario with additional information about the costs of remaining in the euro and responsibility for the crisis. Some randomly-selected citizens were told that the European bailout implied austerity and structural reforms (easier rules for layoffs, expenditure cuts, privatisation, etc.); other citizens did not receive this information. Furthermore, some randomly selected respondents received information attributing responsibility for the crisis to an excessive deficit procedure launched by the EU against Italy; other respondents received information attributing responsibility to the Italian government’s decision to ignore the European fiscal rules; other respondents received no information about who bore responsibility for the crisis.

Results

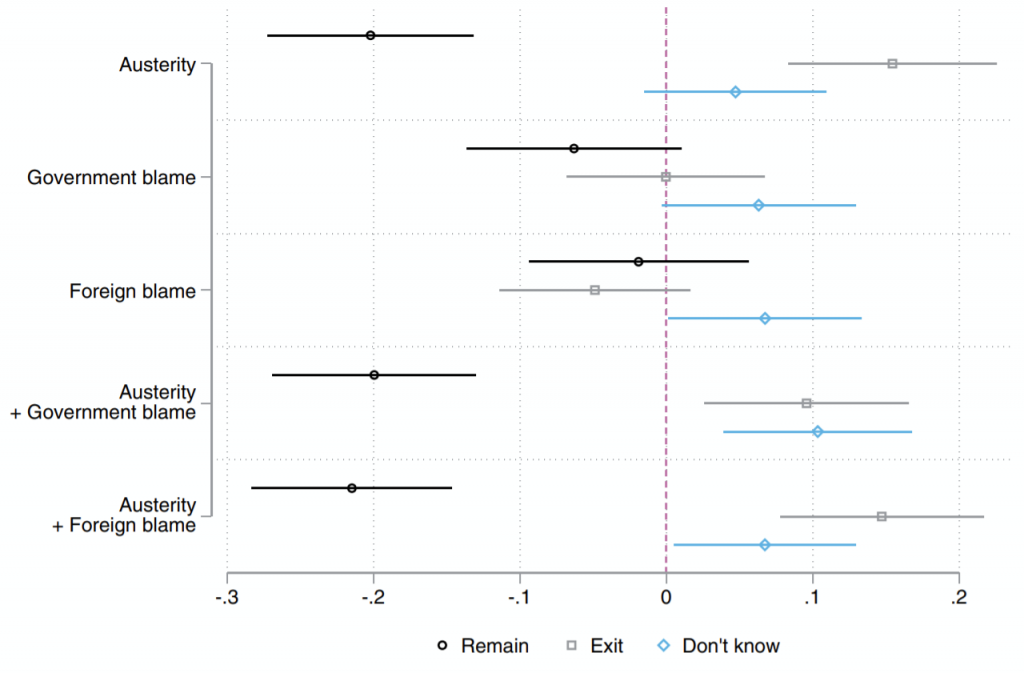

Our results suggest that Italian public opinion is strongly sensitive to the costs of remaining in the euro. If voters are informed that eurozone membership comes at the cost of austerity, support for exit increases by 15% and support for remaining decreases by almost 20%. In contrast, we do not find any significant effect of attributing blame for the crisis to either the Italian government or foreign actors (Figure 1). Apparently, Italian voters do not care much about whose fault the crisis is, but they strongly oppose further austerity.

Figure 1: Average treatment effects of austerity and blame attribution on vote choice in hypothetical ‘Italexit’ referendum

Note: Marginal effects and 95% confidence intervals of austerity and blame attribution are calculated based on multinomial probit models.

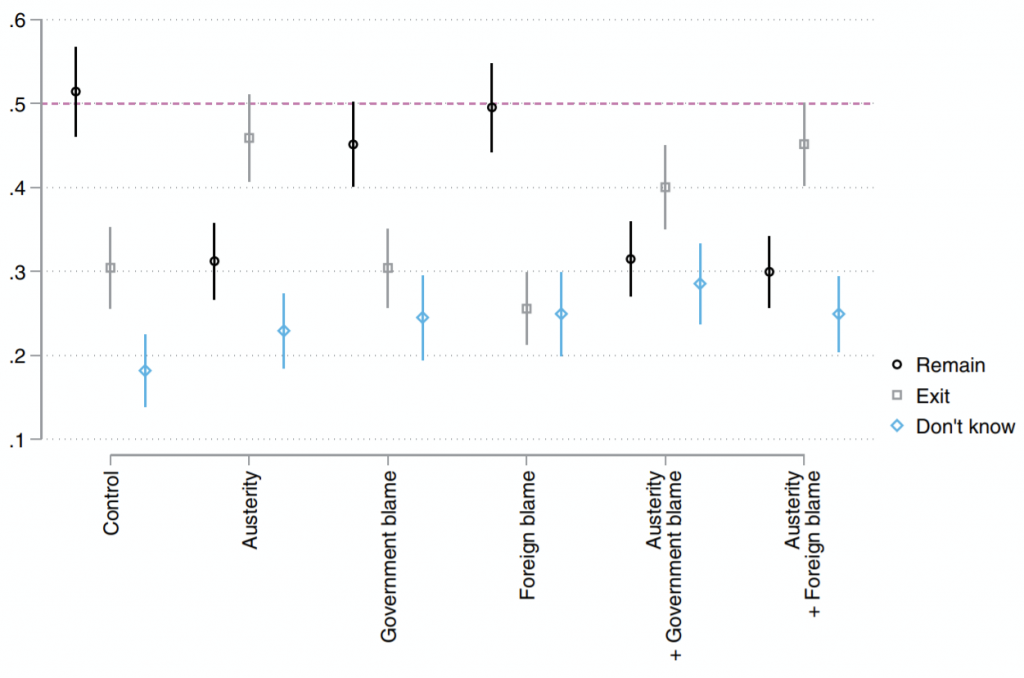

Importantly, when respondents do not receive information about the conditionality associated with a European bailout, a majority wants to remain in the euro. However, informing participants about conditionality produces a relative majority favouring ‘Italexit’ (Figure 2). Overall, our results suggest that opposition to austerity trumps support for the euro in Italy. This implies that the approach to crisis resolution followed by the European authorities so far, based on fiscal consolidation and structural reforms in exchange for financial support, may lead to greater resistance in Italy than it did in Greece and other countries and even to a break-up of the eurozone.

Figure 2: Predicted voting probabilities in hypothetical ‘Italexit’ referendum by treatment

Note: Predicted probabilities of voting in a hypothetical referendum and 95% confidence intervals based on multinomial probit models.

In our study we did not present respondents with information highlighting the costs of exiting the euro, and this narrows our findings. It is possible that preferences for remaining would increase significantly if the costs of exit were to be emphasised and they could counterbalance the decline due to the emphasis on the costs of remaining (austerity). At the same time, the case of Brexit suggests that citizens tend to discount the costs of exit. We plan to analyse how citizens evaluate the costs of remaining vs. exiting the euro in future research.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying article in European Union Politics

Be the first to comment