Understanding the complex interaction between technological change, capital and labour.

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and a prolific blogger.

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts’ blog

Capital expenditure by the ‘hyperscalers’ and tech giants into AI data centres and chips etc continues to pour in. So far, the rise in AI-related investment is not particularly large by historical standards. According to a study by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), at around 1% of US GDP, it is similar in size to the US shale boom of the mid-2010s and half as large as the rise in IT investment during the dot-com boom of the 1990s. The commercial property and mining investment booms experienced in Japan and Australia during the 1980s and 2010s, respectively, were over five times as large relative to GDP.

It may not have reached the extent of railway mania of the 19th century, but it is getting there.

Total IT-related investment, including investment in other IT equipment and software, has risen to 5% of GDP, exceeding its previous peak at the height of the dot-com boom in 2000.

AI-related investment takes a number of forms. The most direct is expenditures on data centres, which house the specific IT infrastructure needed to train, deploy and deliver AI applications and services. Such expenditures include the construction costs of building the physical facilities, as well as spending on IT and other electrical equipment needed for their operation, including servers and networking equipment.

So far, unlike the dot.com boom, which was driven almost entirely by spending by firms using IT products, the current boom is driven by IT-producing firms. But is also changing. Beyond data centres, AI-related investment can also encompass IT manufacturing facilities, which produce the specialised chips and hardware that power these systems. Finally, advances in AI may also spur broader investment in IT products, for example if AI prompts businesses to upgrade their computer hardware or purchase new software.

So AI-related investment has emerged as an important driver of US economic growth. From a negligible contribution before 2022, expenditures on semiconductor manufacturing facilities and data centres have contributed on average 0.4 percentage points (pp) to GDP growth over the subsequent three years.

US data centres are projected to consume nearly 10% of the entire US power grid by 2030. That’s four times the percentage China is forecast to hit. The US has about half of the world’s data centres but only 4% of the global population.

While US manufacturing activity remains subdued, IT investment as a share of US economic output has surged to the highest level since 2001, providing a major boost to overall business investment and activity. Although this IT surge has been concentrated in the United States, it is also generating positive spillovers globally, most notably to Asia’s technology exports.

Total IT investment, which also includes spending by businesses on equipment and software to facilitate AI use, has accounted for almost half of GDP growth in recent quarters, helping to limit the negative adverse effects of Trump’s trade tariffs on growth. Annual spending on data centres alone could increase between $100-225 billion in the next five years. This would see data centre spending alone rise to between 0.8 and 1.3% of GDP, up from 0.5% today.

Enthusiasm for the AI stock boom by financial institutions has hardly dimmed. Nvidia, Microsoft, and Amazon together are planning to invest $60 billion into OpenAI, the ChatGPT designer. Amazon is considering investing $50 billion into the company all by itself; while Europe’s SoftBank is planning to invest $30 billion more. Meanwhile OpenAI is seeking $50 billion from investors in the Middle East.

Firms that are currently driving the AI investment boom have historically operated with substantially less debt than other firms. Instead, they have relied on their highly profitable operations to generate the cash flows needed to fund investments. However, these companies have ramped up their capital expenditures significantly, with investments growing both in absolute terms and as a share of revenues. So the sheer size of these investments is now outstripping cash flow.

Debt financing is becoming more prevalent, increasing leverage. And here is the risk of the bubble bursting, if returns fail to materialize, or if financial conditions tighten. Moreover, profitability from AI investment is very sensitive to the frequent depreciation of chips. This squeezes profit margins and so requires additional debt financing.

Lending by private credit funds (ie outside traditinal banks) to AI-related sectors has grown rapidly, now over $200 billion ie rising from less than 1% of total outstanding loan volumes to almost 8%. Such loans from unregulated sources could triple by the end of the decade. Also many critical AI-related firms are not currently listed on stock markets. Their debt borrowings could have consequences that were not seen during the dot-com era.

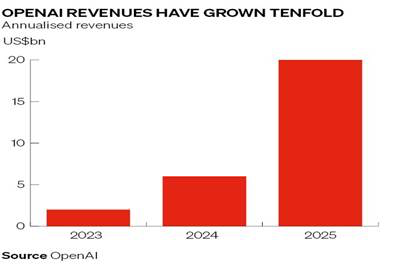

OpenAI is supposedly the leader in the AI race. After launching ChatGPT in 2022, the startup has amassed 800 million weekly active users, more than double the traffic of rival AIs developed by Facebook owner Meta Platforms and Google’s parent Alphabet. But the cost of staying in the race is proving hugely expensive. OpenAI plans to increase its current 1.9GW of compute to 36GW over the next eight years and has struck a series of deals to build data centres and buy cutting-edge chips, which together have saddled it with US$1.4trn of liabilities. Larger rivals like Alphabet and Meta have legacy businesses generating hundreds of billions of dollars a year that they can draw on. OpenAI, by contrast, can only survive for as long as its backers are willing to keep it afloat.

OpenAI has raised more than $60bn since 2015, including US$41bn last year in a round led by SoftBank that was the largest ever seen. But it is set to burn through the last of that cash this year and with profitability still some years away, the question is whether investors are willing to bankroll the giant loss-making venture.The company is now facing a $20bn black hole in its accounts this year, as a series of buy now, pay later deals struck with suppliers including Nvidia, Oracle and CoreWeave start to come due, putting the startup under acute pressure to find new, deep-pocketed investors to secure its future.

This year could be make-or-break for OpenAI. With revenues just a fraction of its rising costs, the projected hole in its finances will grow to about $130bn over the next two years. Open AI is considering a $100bn stock market listing (IPO). That would be three times larger than the biggest IPO ever seen: the US$29.4bn listing in 2019 of Saudi Aramco, which was generating more than $1trn of oil revenues at the time.

So a bursting of the AI bubble is still on the agenda in 2026. The collapse of previous investment booms knocked about 1 pp on average of US real GDP growth. As the BIS puts it: “If a decline in AI investment were to come with a significant stock market correction, negative spillovers could be larger than previous booms suggest. Investors have favoured US equities to gain exposure to AI firms and hidden leverage may lead to credit market spillovers. Overall, while AI may deliver a sustained boost to economic growth, it remains to be seen whether this potential will be realised.” Gita Gopinath, former chief economist at the IMF, has calculated that an AI stock market crash, equivalent to that which ended the dot-com boom, would erase some $20tn in American household wealth and another $15tn abroad, enough to strangle consumer spending and induce a global recession. This is also the view of the IMF. The IMF fears that AI firms could fail to deliver earnings commensurate with their lofty valuations. Even a moderate correction in AI stock valuations would reduce global growth by 0.4%. “ Combined with lower-than-expected total factor productivity gains, and a more significant correction in equity markets, global output losses could increase further, concentrated in tech-heavy regions such as the United States and Asia.”

But even if there is a bursting bubble that pushes the US economy into a recession, perhaps that will only be short-lived, because, there could be a step-change in US productivity levels from widespread AI adoption in all sectors. Many mainstream economists are optimistic that this will happen. Stanford University economist, Eric Brynjolfsson predicts that AI will follow a ‘J-curve’ in which initially there is a slow, even negative, effect on productivity as companies invest heavily in the technology, before they finally reap the rewards. And then the boom comes. Such a J-curve was seen in US manufacturing productivity growth, which fell in the mid-1980s and then after the recession of 1991, accelerated sharply until the mid-2000s

So, first the bubble bursts, then a recession, and then there is a recovery based on AI-related applications – just as there was after the bursting of the railway mania in the mid-19th century. Indeed, this seems to be the view of Trump’s nominee for heading up the US Federal Reserve in June, Kevin Warsh. Warsh reckons AI is going to save the day by boosting productivity so much that it will be a “significant deflationary force”.

Such is the theory of creative destruction first mooted by Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter in the 20th century. His theory has recently been revived by the latest Nobel (Riksbank) prize winners for economics, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt. They argue that the speed of the rise of new firms with new technology and the fall of old firms with old technology is positively correlated with labour productivity growth.“This could reflect the direct contribution of creative destruction”

But ‘creative destruction’ has two parts. Productivity rises but only after the destruction of old capital. Any productivity ‘step-change’ will only be possible through the shedding of labour. The IMF reckons 60% of jobs in advanced economies will be affected. Morgan Stanley economists reckon that Europe’s banks could reduce their workforce by about 10% by 2030. The estimate is based on a review of 35 major lenders that together employ around 2.12 million people. A cut of that size would translate to roughly 212,000 roles disappearing over the next five years. Already, there is evidence that the adoption of AI is hitting the job prospects of America’s workers, according to a study by three Stanford University researchers. This study found “early, large-scale evidence consistent with the hypothesis that the AI revolution is beginning to have a significant and disproportionate impact on entry-level workers in the American labor market.” Already, workers between the ages of 22 and 25 in jobs most exposed to AI — such as customer service, accounting and software development — have seen a 13% decline in employment since 2022.

An AI agent-driven economy is emerging, Consumer AI agents are already beginning to book travel and complete small purchases autonomously for shoppers. Soon they’ll handle more of the end-to-end buying journey in complex purchases: negotiating prices and terms, coordinating delivery and returns, and transacting with other agents at machine speed. The global AI agents market, valued at $5.4 billion in 2024, is projected to reach $236 billion by 2034.

For businesses, this means a growing share of customers won’t be humans at all. They’ll be agents acting on behalf of individuals, interacting with other agents representing sellers, logistics providers and payment processors. A majority of the commercial supply chain could eventually be agent-to-agent.

But historically, there is the other side to the impact of technology. Technological change has been the main driver of employment growth throughout history. Around 60 per cent of workers in the US today are employed in occupations that did not exist in 1940. In the 1840s, Friedrich Engels argued that mechanisation shed jobs, but it also created new jobs in new sectors. In the 1850s, Marx clarified these two sides of creative destruction: “The real facts, which are travestied by the optimism of the economists, are these: the workers, when driven out of the workshop by the machinery, are thrown onto the labour-market. Their presence in the labour-market increases the number of labour-powers which are at the disposal of capitalist exploitation…the effect of machinery, which has been represented as a compensation for the working class, is, on the contrary, a most frightful scourge. …. As soon as machinery has set free a part of the workers employed in a given branch of industry, the reserve men are also diverted into new channels of employment and become absorbed in other branches; meanwhile the original victims, during the period of transition, for the most part starve and perish.” (Grundrisse).

The implication here is that automation means increased precarious jobs and rising inequality for long periods. Daren Acemoglu, Nobel prize winner and mainstream expert on technology reached similar conclusions to Engels and Marx. “I think one of the things you have to do as an economist is to hold two conflicting ideas in your mind at the same time,” he says. “That’s the fact that technology can create growth while also not enriching the masses (at least not for a long time). Technological progress is the most important driver of human flourishing, but what we tend to forget is that the process is not automatic (sic).” Under the capitalist mode of production for profit not social need, there is a contradiction, so “mathematically modelling and quantitatively understanding the struggle between capital — which benefits most from technological advancement —and labour isn’t an easy task.” Indeed.

Be the first to comment