Michael Roberts on a number of topics from November’s Historical Materialism Conference in London

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and a prolific blogger

Cross-posted from Michael’s Blog

As usual it won’t be possible to report on all the many sessions at this year’s London Historical Materialism conference that took place last weekend. I could only attend a few sessions and concentrated, naturally, on ones to do with Marxist economics. Also, I was participating in two sessions myself that clashed with others that I could have reported on.

Nevertheless, there were some interesting and even challenging sessions on the role of money under capitalism, inflation, profitability and the position of monopoly in modern capitalism. In addition, there were several sessions on the theory of imperialism and, of course, on the immediate conflict in Ukraine.

Let’s start with money, credit and monopoly. In a session on this, Nicolas Aquila made an interesting presentation that argued that there is a hierarchy within the money form – at one end, at the international level, there is or was gold, the universal money. Now in the 21st century, gold has been replaced at the head of the hierarchy by the US dollar, in effect a quasi-world money. Then we move down the scale to the secondary currencies of advanced capitalism: the euro, yen, pound etc. At the bottom internationally are the weak currencies of the so-called emerging economies. It’s a sliding scale of currency sovereignty. This hierarchy, Aquila argues, explains the lack of sovereignty over money in the weaker economies and their exposure to currency crises.

In the same session we were offered a new version of the post-Keynesian theory of monopoly capitalism: ie profits arise from corporate mark-ups over costs. This is particularly the case for monopolies that now dominate knowledge markets and can set prices rather than compete with others where prices are given. Cecilia Rikap and Cedric Durand argued that in this era of intellectual property and knowledge production, companies have a monopoly over innovation (like algorithms) and so have established permanent monopoly power. It is no longer a question of monopoly in markets but power over innovation.

This version of Kalecki style monopoly capitalism was not convincing to me. Do we really think the current media and tech ‘monopolies’ will be with us forever? Monopolies come and go as innovations change and new companies appear – from GM in autos; to GE in electronics etc. Do we really think this time it will be different?

Monopoly or oligopoly cartels have existed since the development of mature capitalism and there has been an increasing degree of concentration of capital, as Marx predicted. But there is no empirical evidence that increased concentration of capital and ‘monopoly power’ in certain sectors have reduced cutthroat competition – on the contrary. Durand’s point that large companies plan their investment, sales and production internally does not mean that they can avoid perpetual and turbulent competition – indeed I refer you the devastating refutation of the ‘monopoly capital’ model by Anwar Shaikh, best expounded in his theory of ‘real competition’ versus monopoly (see chapter 8 of his book, Capitalism) and this: https://www.anwarshaikhecon.org/sortable/images/docs/publications/political_economy/2019/Capitalism_Book%20_Logical_Structure_2019.pdf

Then there was the debate about the nature and causes of modern imperialism. Readers of this blog will know that Guglielmo Carchedi and I have published a paper on the economics of modern imperialism, in which we argue with empirical evidence that the economic core of modern imperialism is the unequal exchange of value (surplus value) through international trade (and capital flows) between the advanced capitalist economies and the rest of the world. It is the persistent and pervasive transfer of value to the advanced economies from the rest that best characterizes the former as imperialist. Exploitation of the global south by the imperialist bloc is not mainly the result of ‘super-exploitation’ of the workers of the south or through the monopoly of markets and finance in the north; but through the redistribution of surplus value from the technologically backward economies to the technologically advanced, both through unequal exchange in trade and through the repatriation of profits, interest and rent by multi-nationals and banks.

Now our thesis was challenged by Charlie Post who also rejected the super exploitation and Leninist monopoly finance theories. He argued that using aggregate or average measures of the technological superiority of imperialist economies over those in the Global South failed to pick up sectors where the latter had already gained superiority. In particular, Charlie was arguing that China has become a leader in many sectors and so could not be considered just another exploited economy, but increasingly should be considered a future entrant into the imperialist bloc.

And yet in our paper, Carchedi and I had shown a large net transfer of surplus value from China to the imperialist bloc which we defined as the G7 plus a few other economies in the Global North. All have persistent and significant net value transfers from the rest of the world. On this definition, China (or for that matter, Russia) was not an imperialist state or economy. Moreover, no country since Japan and the US in the late 19th century has joined the imperialist club since 1915 when Lenin identified these imperialist nations – unless you consider tiny Taiwan or South Korea as entrants.

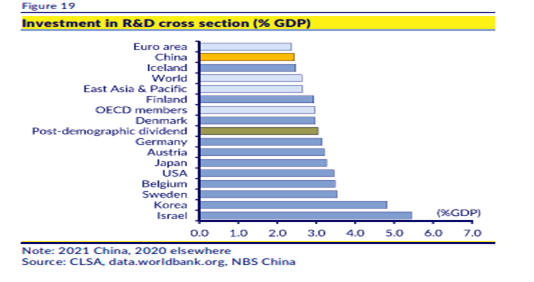

Will China become a ‘late developer’ and budding imperialist power? I doubt it. It is still a long way behind on technology and productivity levels, even though it has made the fastest process of catching up in history. One comment from the floor in the session was that “it was a no-brainer that China was capitalist and imperialist”. Well, instead I have put my brain to work to show that China is not only not imperialist in the sense defined above, it is also not capitalist (yet). See my many posts on this here. What is clear is that US imperialism is out to ensure that China does not catch up.

I won’t now go into the discussion about whether ‘super-exploitation’ is the main way in which the workers of the Global South are exploited by imperialism, as this is dealt with in detail in our imperialism paper and also in several posts in my blog. Suffice it t say that low wages are not a definition of super-exploitation which refers when wages are below the value of labour power ie below levels of subsistence. That is prevalent in the Global South but not in my view decisive in explaining the transfers of value to the imperialist bloc – ‘normal’ exploitation does that.

In another session, Andrea Ricci and Giusseppe Quattomini delivered an excellent short presentation on the importance of unequal exchange in international trade and why Marx developed this theory of trade. For Marx, capital is about a world economy not a national one. In a national economy, there is transfer of surplus value between sectors from the most backward technologically to the most advanced, leading a move towards an average rate of profit. This redistribution follows that same logic in international trade.

Ricci and Quattomini agree that imperialism is thus first an economic concept. And imperialism is the result of the expansion of advanced capital into global markets to achieve that transfer of value. Henryk Grossman once explained that the rise of modern (economic) imperialism in the late 19th century was the result of falling profitability of capital in home markets – see Grossman The Law of Accumulation p 181.

That is partly why it is difficult to accept the analysis of the US rate of profit in the last 70 years presented by Bill Jefferies in the same session. He argues that, contrary to most other studies of the US rate of profit (including my own), the rate has been rising since at least the 1990s and particularly after China entered the World Trade Organisation in 2002. His results imply that Marx’s law of falling profitability had no role to play in causing the Great Recession in 2008-9. Jefferies claims that all previous studies were based on measures of fixed capital assets provided the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). And those constant capital measures are useless because they are based on the neoclassical concept that capital assets as just the accumulated flow of future profits. Instead, they should be based on the actual capital advanced. So Jefferies uses the measures of ‘depreciable assets’ provided by the US Internal Revenue Service obtained from the tax accounts of companies. In doing so, this reduces the size of constant capital (c) in Marx’s rate of profit formula (s/(C+v) by over 70% from the BEA data. Thus, profit rates are much higher and also, it seems, not falling – at least not since 1990.

I was not convinced. First, it is not correct that the BEA uses constant capital advanced just based on the present value of future profits. The BEA fixed asset measures may start with such an arbitrary figure, but each year the rise is based on profits from the future year as invested. Second, when we look at the BEA data (Table 7.13), we find a reconciliation between the IRS and BEA data that shows no large difference in the value of fixed assets or their depreciation. So there are serious doubts about Jefferies’ data and method.

Let me now turn to the session in which I introduced a presentation by Guglielmo Carchedi and me on: A Marxist theory of inflation. We have been working and developing our approach for some time and this was the latest version of our theory at a very opportune time given the rocketing inflation now engulfing the major economies around the world since the end of the COVID slump. The inflation session.

The presentation can be found here. The gist of the theory is that there are two structural factors that drive the inflation (or deflation) of prices of commodities in a modern capital economy. The first is the rate of change in new value produced in capitalist production; new value being net value in a commodity after accounting for constant capital (depreciation of fixed assets and raw materials). The second is the intervention of the monetary authorities to adjust the rate of change in the money supply. The rate of change in new value tends to slow in capitalist production because more investment is directed towards the means of production or constant capital instead of towards investment in more labour (power). This is because the capitalists want to boost the productivity of labour with technology to lower costs in competitive markets. But in so doing, this will reduce the labour time involved in each unit of production. A rising organic composition of capital (c/v) will tend to lower the rate of profit on capital invested and thus new value growth will tend to slow.

In what we call our value rate of inflation theory, slowing new value growth would mean slowing inflation of prices; and in slumps, deflation. But there is a counteracting factor to this long term tendency, namely changes in the money supply, and in a modern economy where the money supply is controlled by the banking system and the state, this can act in the opposite way and raise inflation. As the monetary authorities try to boost growth with cheap money, they exert upwards pressure on inflation rates. In our paper, we show that the combination of these two factors (properly measured) can explain a very high proportion of the changes in consumer price inflation.

There were some questions at the session about the veracity of this theory and the empirical evidence and there have been some critical attacks on its validity since. I won’t deal with these in this post but I think the discussion on a Marxist explanation of inflation must continue. Suffice it to say now that, if you look at the slides, our presentation offers firm evidence against the two mainstream inflation theories (monetarism and wage-cost push) and also some differences with Anwar Shaikh’s ‘classical’ inflation theory.

Finally, there was the well-attended session on the Ukraine conflict in which I was asked to participate on the economics of the war and its global implications. The other speakers included Ilya Budraitskas who argued, as far as I could tell, that Putin started this war because of growing opposition from dissidents at home which threatened his domestic popularity. I found this difficult to believe as the main reason for the invasion.

Volodymyr Ishchenko seemed to argue that we should characterize Putin’s Russia as a form of ‘political capitalism’, a term promoted by Branco Milanovic, the former World Bank economist and expert on global inequality. Milanovic’s concept is developed in his recent book, Capitalism Alone, in which there is no possibility of socialism and so the choice before us in the 21st century is either a free market unequal ‘liberal democratic’ capitalism as in the US and Europe; or ‘political capitalism of a state-led autocratic nature as in Putin’s Russia or Xi’s China. “Capitalism gets much wrong, but also much right—and it is not going anywhere. Our task is to improve it.” says Milanovic. Milanovic’s characterization seemed to take Ishchenko down the road of arguing that Putin was a fascist or at least a ‘semi-fascist’.

Vladimir Unkovski-Korica took a different view of the cause of the war. He saw it as a culmination of a growing global conflict between NATO powers seeking to reduce the strength and influence of Russia and on the other side Russia trying to maintain its control over the former post Soviet border countries. Ukraine has become the plaything of forces on both sides. Vladimir argued a peaceful settlement could have been reached with the Minsk accords but Ukraine’s government and the US rejected that.

My own presentation concentrated on the economics. Because of technical problem, I did not present my slides on the Ukraine and Russian economies – here they are.

The gist of what I said was 1) Ukraine has been devastated by the war; apart from the loss of life and homes, Ukraine’s infrastructure has been decimated and Russia is controlling important areas of resources and industry – in a country that remains one of the poorest in Europe.

And 2), the aim of the foreign backers of Ukraine and its current government after the war is to introduce a free market economy with massive foreign ownership and privatization of the key assets including land and agriculture, with the removal of labour and trade union rights; with a reduction in regulation of finance and the environment. 3) Putin’s Russia so far has coped with the sanctions on oligarchs, trade and finance because it has been able to sell its oil and gas. But now Europe is increasingly reducing its demand for these and price caps are planned for Russian oil exports. This could reduce the revenues for war that Putin has accumulated.

Longer term, the technological sanctions on Russian industry will weaken its ability to grow. Globally, in many way, US and NATO policy and actions are a dress rehearsal for the real conflict between the US-led imperialist bloc and China (over Taiwan) that is coming in this decade.

Finally, I note that the winner of this year’s annual Isaac and Tamara Deutscher prize was Gabriel Winant’s The Next Shift: the fall of industry and the rise of healthcare in rust belt America. I hope to review that soon.

But above all, please note that Capitalism in the 21st Century – through the prism of value by Guglielmo Carchedi and myself is now published by Pluto. The book covers Nature and the Environment; Money and Inflation; Crises; Imperialism; Knowledge and Computers; and the nature of Socialism. I shall be reviewing parts of the book over the next few months.

Be the first to comment