Indonesia, with the fourth largest population in the world, goes to the polls, with the oligarchs who emerged under the brutal dictatorship era of Suharto still exerting control.

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and a prolific blogger

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts’ blog

Indonesians will elect the country’s next president today (14 February). Indonesia is the world’s fourth-most-populous nation with over 280m people living in a myriad of archipeligo islands spanning Asia to Australia. More than 204 million people are eligible to cast ballots in the world’s largest direct presidential vote, the fifth since the Southeast Asian country began democratic reforms in 1998. More than half of those eligible to vote are aged between 17 and 40 and about a third are under 30.

The winner will succeed President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, who is constitutionally barred from seeking a third term and will step down in October after ten years in office. Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto, 72, is the front-runner in the presidential race. Prabowo is a former general with the army’s special command and former son-in-law of the late Indonesian military dictator President Suharto.

Ganjar Pranowo, 55, is a former governor of Central Java and a senior politician with the ruling Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), to which Jokowi currently belongs. The other candidate, Anies Baswedan, 54, is the former governor of Jakarta. He is a former university rector and political scientist. During Jokowi’s first term he served as education minister. However, after being ousted in a cabinet reshuffle, he joined the opposition. Anies paints himself as an alternative to Prabowo and Ganjar as he seeks a break from Jokowi’s policies.

Final opinion polls by major pollsters show support for Prabowo exceeds 50%. So he is the most likely winner. If no candidate gets 50% in the first round, there will be a second round run-off between the top two. All three candidates demonstrate that Indonesia’s 21st century democracy is still dominated by the political, business and military leaders who built their fortunes during thirty-two years of Suharto’s authoritarian rule.

Indonesia gained independence from Dutch imperialism after a long hard fought war. The nationalist Sukarno became its president, leaning on the support of the independence fighters who were mainly led by the Communist party based in the countryside. In 1965, in the midst of an economic crisis, military chief Suharto came to power through a coup in that ousted Sukarno. Suharto’s takeover led to a bloodbath in which up to 1 million Communists and nationalists were killed and another 1.5 million imprisoned. The CIA described the purge as “one of the worst mass murders of the 20th century”. Suharto’s coup was even worse than Pinochet’s military coup over Chile’s President Allende nearly a decade later in 1973.

In 1975 Suharto also launched a bloody invasion of part of one of the archipelago islands, previously a Portuguese colony, East Timor, to crush its independence movement and annex it as Indonesia’s 27th province (the other half of the island, West Timor, was already part of Indonesia after independence from the Dutch). An estimated 200,000 local people died during the occupation that lasted until 1999, when finally, independence was achieved for East Timor when Suharto was removed from power.

Indonesia’s economy has rested on its oil and gas reserves and the produce of its land. In the early 1980s, the Suharto government responded to a fall in oil exports during the early 1980s oil crisis by trying to shift the basis of the economy to cheap labour-intensive manufacturing. Foreign investors came in to take advantage of Indonesia’s low wages.

It was under Suharto that the country’s modern oligarchs first emerged and his reign was littered with examples of close friends and family obtaining preferential access to loans, concessions, import licences and state bail-outs. Aafter over three decades of his dictatorship, the Asian debt crisis of 1998 brought down the Suharto regime. In the face of growing public protests against his authoritarian rule, Suharto’s own military and political allies forced him to resign. Free elections were held within a year.

The biggest winner then was the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDIP), led by Megawati, daughter of Sukarno. But Suharto’s Golkar party, led by regime loyalists from business and military backgrounds, and the Muslim United Development Party had sufficient support to block Megawati. Since then, all so-called parties of the democratic era have been led by Suharto-era businessmen and retired military generals. As only parties with at least 20 percent of seats in the parliament can field a candidate, that has ensured the continued political control of this elite.

Current president Joko Widodo was the only outsider to breach this clique. In 2014, voters and Megawati’s party backed him to end the control of Suharto cliques. Widodo soundly defeated Prabowo Subianto. But soon Widodo fitted into the existing ruling elite by bringing the oligarchs and politicians into his administration. He appointed Subianto as his defence minister and Subianto’s party joined the governing coalition, while Jokowi closed down the anti-Corruption Commission that was investigating Suharto’s supporters.

Now in 2024, it is Subianto who looks set to become President at his fourth time of trying. He has lined up Widodo’s eldest son to be his vice presidential running mate, while Widodo himself is planning to take up the chairmanship of Subianto’s Gerindra party, shifting from Megawati. It‘s going to be a tight coalition of ‘business as usual’.

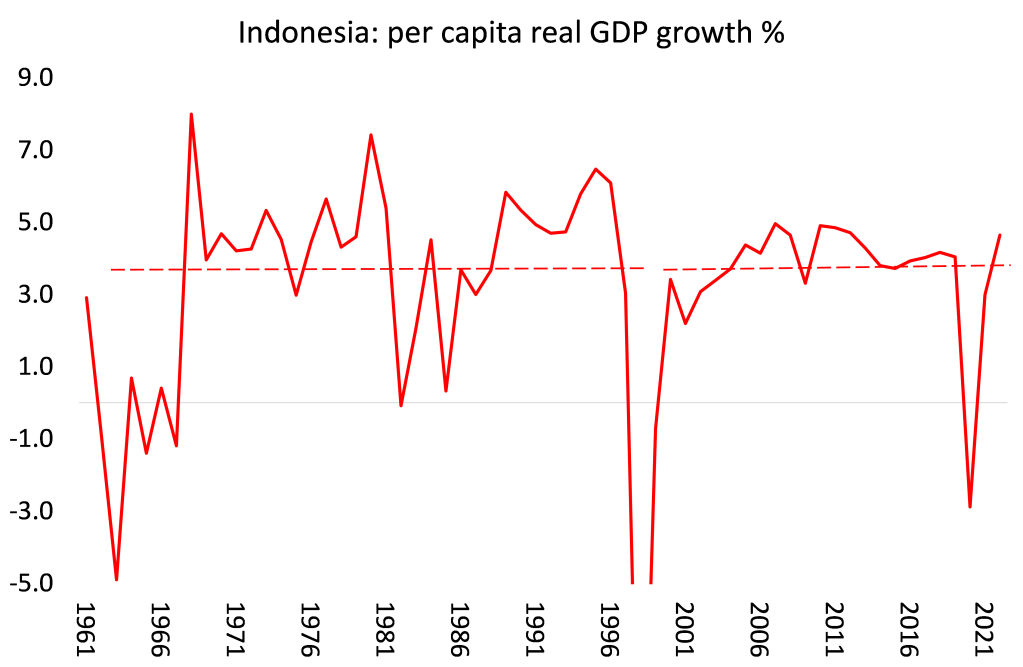

Jokowo’s eight years are regarded in the Western media and among mainstream economic circles as a great success, with average real GDP growth at around 5% a year. And he appears to remain very popular with the electorate.

But Indonesia’s apparent success is superficial. For a start, per capita income growth is much less, at under 4% a year.

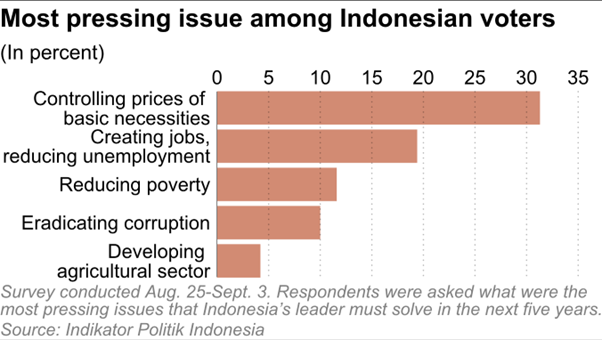

As always, what matters to Indonesians (outside the elite) are living standards and decent jobs.

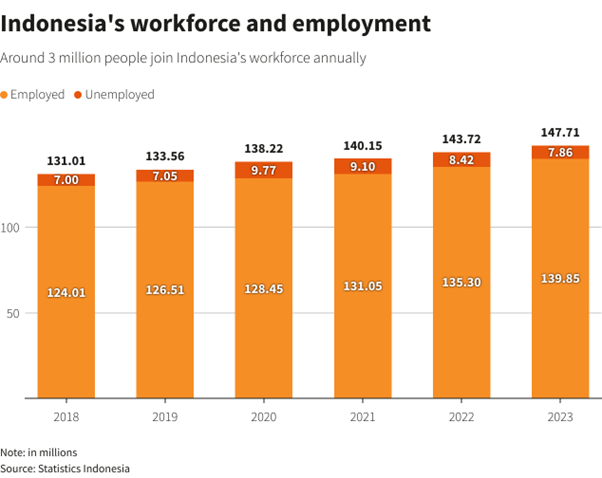

The elite claim that Indonesia can become a ‘high-income nation’ by 2045, when it celebrates 100 years of independence. And all the presidential candidates are promising upwards of 15 million new jobs in the next five years, in a country where about 3 million people enter the job market annually. But most estimates reckon that Indonesia needs 7% economic growth annually to churn out enough jobs for its young population and the growth forecast for the next two years is closer to 4% a year. Around 1,000 jobs were created for every trillion rupiah of investment in 2022, compared with 4,500 jobs in 2013.

These jobs are supposed to be generated by moving away from an economy based on mining, oil production and single crop agro exports (palm oil), which are mainly capital intensive to a more broad-based manufacturing and hi-tech economy like China or Vietnam. There is little sign of that. Instead, it is nickel mining for EV batteries that is the main investment. Investment in nickel mining and refining has created only a limited number of jobs and still relies heavily on skilled foreign labour, particularly from China.

As a result, job creation has plunged. Officially, Indonesia’s unemployment rate is 5.3%, but people are considered employed if they work just a few hours a week. Nearly 60% of workers are in the informal sector i.e. they are casual workers, with no rights, sick pay or even guaranteed wages. Young people aged 15 to 24 made up 55% of the 7.86 million officially unemployed in 2023, up from 45% in 2020.

The lack of jobs and the emphasis on capital-intensive industries owned and controlled by the Suharto oligarchs and foreign companies has widened the inequality of wealth and income – a trend in all peripheral economies. The top 1% of income earners take 18% of all personal income in Indonesia, more than the bottom 50% who take just 12% between them. It’s even more unequal with personal wealth, with the top 1% holding 41% of all personal wealth, the top 10% with 61% and the bottom 50% with just 12%.

In the past two decades, the gap between the richest and the rest in Indonesia has grown faster than in any other country in South-East Asia. It is now the sixth country of greatest wealth inequality in the world. As this election takes place, the four richest men in Indonesia have more wealth than the combined total of the poorest 100 million people. The vast majority of the land is owned by big corporations. At least 93 million (36 percent of the population) of Indonesians are below the World Bank minimum poverty level.

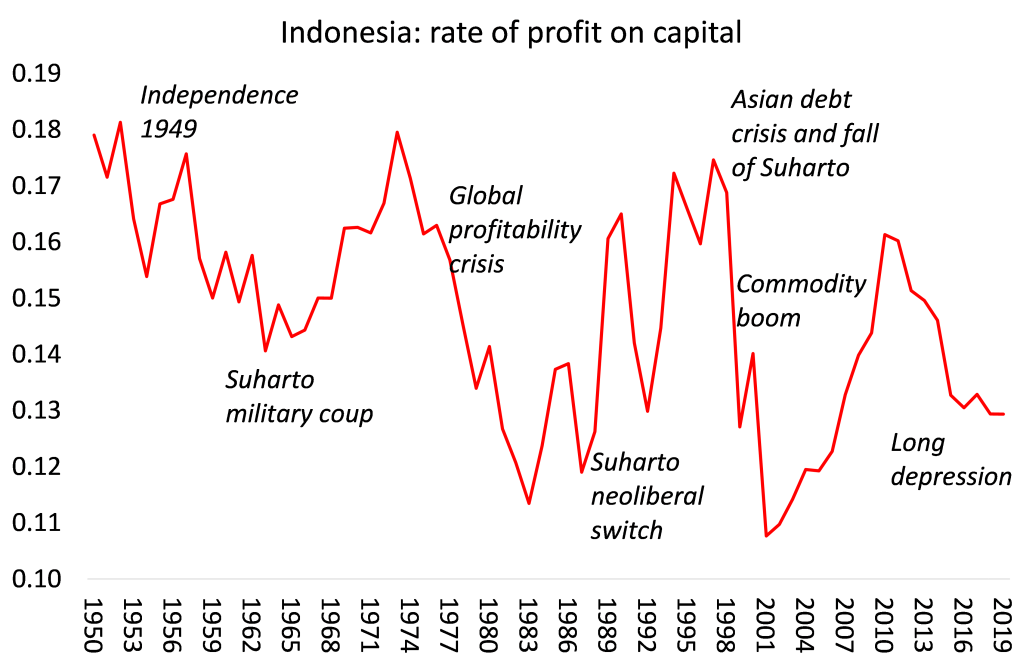

Inequality rose fast when Suharto switched from a development policy based on state fusion with the oligarchs to the neoclassical model of the 1980s onwards of deregulation, privatization and the abolition of subsidies on basic commodities, in order to boost the profitability of Indonesian capital that had taken a hit during the global profitability crisis of the 1970s.

But the Asian financial crisis of 1997-8 exposed this neoliberal development model and Indonesia fell back on IMF funding and its Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) that imposed austerity and more ‘flexibility’ in the labour market. Suharto was forced out, but his successors continued to accede to this ‘structural adjustment’.

Then came the commodity boom of the early 2000s. This time, expansion was based on less on minerals and oil and instead on palm oil exports. Indonesia is the world’s biggest producer of palm oil, a ubiquitous ingredient in a wide range of goods ranging from processed foods to cosmetics and biodiesel. Between 2000 and 2008, the ten largest palm oil companies controlled the industry and most of the ten richest men in Indonesia have palm oil in their portfolios.

But production of the commodity has long been associated with the wholesale clearing of tropical rainforests, burning of peatlands, destruction of endangered wildlife habitat, land conflicts with Indigenous and traditional communities, and labor rights abuses. According to one analysis, rainforests spanning an area half the size of California, or 21 million hectares (52 million acres), are at risk of being cleared.

There are still 3.1 million hectares (7.7 million acres) of plantations for which forests had been cleared for plantation. But they are not being developed because the commodity price boom is over, for now. As a result, the profitability of Indonesian capital had fallen back in the last 10 years, which is reducing investment growth and weakening economic growth.

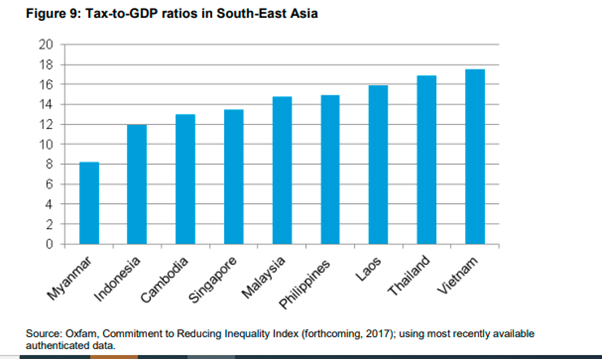

The Suharto elite and the Indonesian oligarchs remain firmly in control. The rich are not taxed properly. The OECD considers Indonesia to have the worst tax administration system of any South-East Asian country and it has the second lowest tax to-GDP ratio in South-East Asia. So the government consistently misses its already low tax revenue targets.

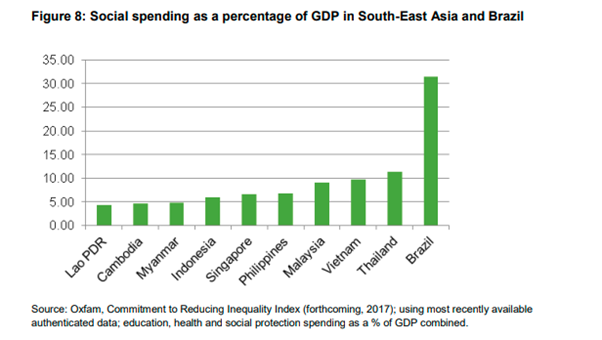

The IMF has calculated that the country has a potential tax take of 21.5 percent of GDP. If it were to reach this figure, it could increase the health budget nine times over.

Much is made of Indonesia’s supposed universal health coverage, but health spending is still equivalent to just 1 percent of GDP, which is very low by regional standards; for example, in Vietnam health spending is 1.6 percent of GDP and in Thailand 2.1 percent. And some 90–100 million Indonesians are still not covered after the health reforms, and the government has failed to reduce out-of-pocket payments (OOPs) for health services – the most regressive form of health financing. OOPs still constitute 47 percent of total health spending in Indonesia – the same level as 20 years ago. Informal workers must pay a regressive premium in order to benefit. So private hospitals proliferate and the privatization of facilities has meant that many Indonesians have been priced out of health services altogether. For example, in Kupang the privatization of Yohannes General Hospital has caused costs to skyrocket by up to 600 percent.

Likewise, the education system is underfunded; there are barriers to equal access and it does not provide Indonesians with the skills needed to enter the workforce, meaning that millions of workers are unable to access higher-skilled and higher-paid jobs. Despite an annual increase in spending on education in nominal terms, the education budget as a percentage of GDP is still only 3.4 percent – below UNESCO’s standard for education spending of 4–6 percent of GDP. The lack of government spending on education has led to a proliferation of private schools, which now account for 40 percent of all secondary school enrolments.

None of these issues are being addressed by the presidential candidates, most of whom are obsessed with Jokowo’s ambitous plan to shift the nation’s capital from the congested mess that is Jakarta to a new site in Borneo at exorbitant cost.

The Indonesian economy has yet to return to its pre-pandemic growth trajectory and it is unlikely to do so. This reflects the ‘scarring’ effects from the pandemic, including in labor markets and productivity growth. And Indonesia’s oil and gas reserves will be exhausted in the next ten years. So even the current inadequate growth rate is threatened.

Indonesia has got the classic formula for development in poor countries in the world of 21st century imperialism. Its economy is founded on basic commodity production that is highly capital intensive, severely damages the environment and does not provide many good jobs for the people, while the rich pay little tax and public services are limited. And the old Suharto elite remain in control.

Thanks to many generous donors BRAVE NEW EUROPE will be able to continue its work for the rest of 2024 in a reduced form. What we need is a long term solution. So please consider making a monthly recurring donation. It need not be a vast amount as it accumulates in the course of the year. To donate please go HERE.

Be the first to comment