Japan, like most developed nations, seems to be caught up in a political malaise as voters lose confidence in their political class

Postscript: The LDP secured more than 233 lower house seats – enough to govern without its coalition partner Komeito. Ovter turnout was just under 56%.

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and a prolific blogger

Cross-posted from Michael’s Blog

There is one G7 leader who won’t be at the Glasgow COP26 or G20 meeting in Rome this weekend. That is Japan’s new prime minister Fumio Kishida, who, after replacing the unpopular Yoshihide Suga as leader of the ruling Liberal Democrat party, has called a snap general election.

Kishida is putting at serious risk the majority for his party in the election. The LDP has lost support through its handling of the COVID crisis and because of the failure of the economy to make any significant recovery from the pandemic slump in 2020. Opinion polls suggest that the LDP’s representation could be reduced from 275 seats in the previous parliament to just 233 seats this time. The LDP would lose its outright majority and be forced into a coalition with its tame junior coalition party Komeito to sustain power.

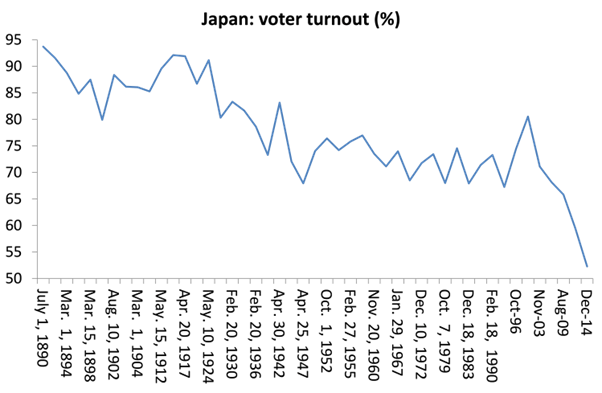

Voter turnout will be crucial. Higher turnouts tend to help the opposition parties, who have united tactically to reduce the LDP majority. But the disillusionment with party politics in Japan, which I have reported on before, looks like continuing, especially among the young. The overall turnout could be as low as the post-war low of 52.7% in 2014 and lower than the 2017 turnout of 54%, with only one-third of 18-24 year-olds bothering to vote.

Kishida is a former banker, no surprise there, and claims that he is going to revive the Japanese economy with what he calls a “new capitalism”, which is supposedly a rejection of ‘neoliberalism’ as operated by previous PMs like Abe, with his ‘three arrows’, and aims to reduce inequality, help small businesses over the large and ‘level up’ society. This would break with Abe’s emphasis on ‘structural reform’ ie reducing pensions, welfare spending and deregulating the economy.

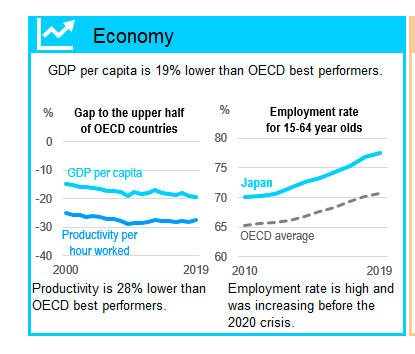

Japan remains over 30% less productive than the US and Kishida wants to cut ‘red tape’ and get more women and seniors into gainful employment, with efforts to raise social benefits for those in non-regular work up to the same level as Japan’s “salary men.” A new Public Price Evaluation Review Committee will aim to lift wages for carers and childcare staff, and Kishida has called for more support for schooling and housing costs for parents.

Action is certainly needed on the economy. After decades of slow real GDP growth (only compensated for by a falling population), the recovery from the pandemic slump (recording a 4.5% contraction) looks very weak. Japan has lagged behind other G7 economies.

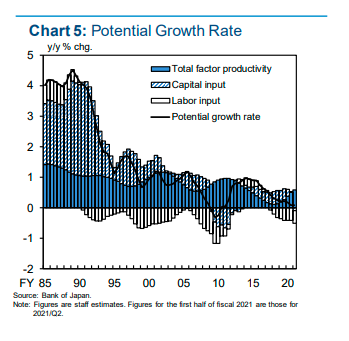

The overall economy has remained in recession until very recently. The au Jibun Bank Japan Composite PMI was up to 50.7 in October 2021 finally suggesting the first expansion in private sector activity in six months. Even so, GDP is projected to expand by only 2.6% in 2021 and 2% in 2022. Indeed, the BoJ reckons the long-term potential growth rate will be close to zero!

Business investment is expected to pick up as corporate profits improve (if still below pre-pandemic levels), but public sector investment is stagnant. Inflation is still running well below the Bank of Japan’s 2% target. Wage growth has been stagnant — total cash earnings were virtually no higher than they were a year earlier despite weakness last year.

Japan was known as the major manufacturing economy of the 20th century but with the rise of China and rest of east Asia, Japan’s export share has fallen.

Japan is now putting its hopes on the new Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a Asian trade agreement including China that covers about 30% of the world’s population and output. The pandemic has delayed other countries’ ratification, which is a requirement for the multilateral agreement to become effective. Once it goes into effect, the RCEP could add $500 billion to global trade by 2030. The partnership is particularly important for Japan as it lowers tariffs for Japanese exports to China and South Korea, two of its three largest trading partners.

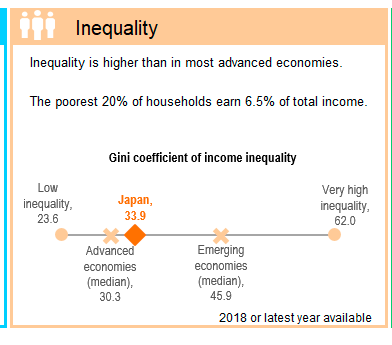

Kishida talks about reducing inequality and Japan’s inequality of income measures are higher than in most advanced capitalist economies.

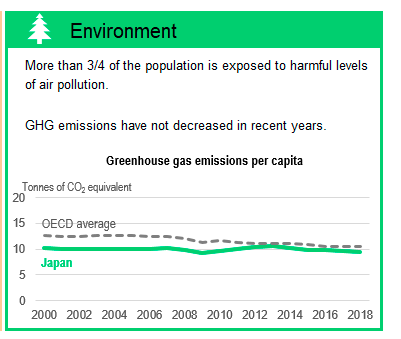

And when it comes to dealing with the environment, the LDP’s record is hardly successful.

After the failure of Abenomics in the decade after the Great Recession, Kishida has his work cut out to deliver his ‘new capitalism’ in the decade after the pandemic.

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge, please donate here.

Be the first to comment