As Joe Biden’s administration starts to challenge the democracy-warping powers of giant multinationals, Britain and Europe risk being left behind

Michelle Meagher is co-founder of Balanced Economy Project, competition lawyer and author of ‘Competition Is Killing us’

Nicholas Shaxson is a journalist, a co-founder of the Balanced Economy Project, editor at BRAVE NEW EUROPE; and author of ‘Treasure Islands’

Cross-posted from Open Democracy

n January 2017, the Yale Law Journal published a paper entitled ‘Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox’, by a little-known young journalist and scholar called Lina Khan. Softly and clearly, Khan delivered a wrecking ball to the cosy and corrupt global consensus on corporate power that has prevailed since the 1970s. It’s this consensus that has allowed the emergence of monopolising giants, such as Amazon, Google, Citigroup and Walmart, in nearly every economic sector you can think of.

Some academics, lawyers and lobbyists – many funded by tech giants – snickered at her radical ideas. Yet just four years later, at the age of 32, Khan would be appointed to be chair of one of the world’s most powerful economic regulators, the US Federal Trade Commission.

Her appointment in June was no isolated act on the part of Joe Biden’s administration. In recent months, a number of others with similar ideals have been appointed to powerful positions, notably lawyer Jonathan Kanter to head the Department of Justice’s antitrust division, and legal scholar and writer Tim Wu as a special adviser to Biden at the National Economic Council. Crucially, their nominations gained some Republican support.

Together, these appointments represent the latest stage in the evolution of one of the most thrilling and influential civil society movements in modern history, which has seen the US this year suddenly streak far ahead of the UK and Europe when it comes to tackling the democracy-warping powers of the world’s biggest multinationals. If these gains can be consolidated and extended, and expanded outside the US, it is no exaggeration to say that this could transform our societies and economies for the better.

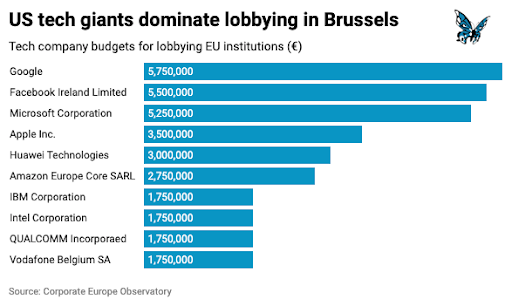

Like the US, the UK and Europe are struggling to keep up with the 21st century’s corporate giants. This is especially the case when it comes to the tech giants’ ‘move fast and break things’ model of aggressive expansion, monopolisation and political capture. The European Commission is currently putting together a ‘Digital Services Act’ to regulate the 10,000-odd online platforms in the EU, and a ‘Digital Markets Act’ to focus on large ‘gatekeeper’ tech platforms, like Amazon. Meanwhile, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) is creating a Digital Markets Unit, whose powers have not yet been legislated but which will focus on regulating large digital platforms with so-called ‘Strategic Market Status’ – big players, such as Google or Amazon. The EU and UK initiatives will have some impact, though after an insufferable time delay. Our regulators are up against immense forces: researchers recently identified 612 separate bodies lobbying for the digital industry in the EU, of which the biggest spend several millions apiece. Beyond the digital world, however, progress on tackling the dominance of giant firms is slower still.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. The share of global income that accrues to workers (as opposed to owners, shareholders and so on) has fallen by around six to eight percentage points since 1980. If today’s workers earned the same share of global income they did back then, they would receive $6trn more each year. That is an order of magnitude greater than the estimated $400-$600bn in annual losses to tax abuse. Technological change and globalisation are big reasons for this decline in the labour share, alongside lax competition enforcement. Economists in the field increasingly agree that anti-monopoly is where the big solutions lie.

Anti-monopoly includes what Americans call ‘antitrust’ and in the UK we call ‘competition policy’. This refers to using the power of government to push back directly against excessive concentrations of corporate power, such as blocking mergers or breaking up dominant firms and regulating their behaviour effectively – as well as using more indirect methods such as tax, transparency, labour laws or financial regulation, to provide guard rails against excessive power. The problem, however, is that our regulators have developed a giant ideological blind spot, which has hidden the elephants in our economic rooms.

How the world got ‘Borked’

In the 1970s, a group of well-funded activist-academic economists, mostly based at the University of Chicago, began militating for a set of new ideas that became widely known as ‘neoliberalism’. The core idea was that competitive markets were efficient, and the simplistic solution was therefore to push for radical programmes of privatisation, so that anything from football fields to care homes to national tax systems could be shoe-horned into the competitive process, where the efficiency machine of this ‘universal market’ would sort the wheat from the chaff to create the best of all possible worlds. The most famous high priests of neoliberalism were the American economist, Milton Friedman, and the Austrian-British economist, Friedrich Hayek.

But on corporate power, their leader was a different person: a terrifying conservative lawyer called Robert Bork, who wielded a slightly different set, albeit related, of ideas. Bork argued that antitrust regulators, courts and the public should stop worrying about namby-pamby things like power, inequality, democracy, citizenship, sustainability, worker welfare, small businesses, economic diversity, resilience or the structure of markets. Instead, he felt, we should narrow our focus down to just two things that economists could easily measure: prices and consumer welfare on the one hand, and a narrow concept of economic ‘efficiency’ on the other.

Bork’s subtext was simple: if corporations grow bigger they can reap economies of scale and scope, thus becoming more ‘efficient’, and then hand those efficiencies out to consumers via lower prices and better services. Markets were efficient, he argued, so if firms wanted to merge, that was efficient. Hey presto! Big was good, and corporate giants were the best friend of the little guy. In Bork’s world, today’s Amazon would be ideal: cheap goods, delivered efficiently. Google or Facebook, with their apparently ‘free’ services, perhaps even better. Never mind their workers, or whole economic ecosystems dragged down into their suffocating gravitational embraces, or politicians bent into serving their wishes, or fake news, or teenage girls self-harming, or desolate high streets and communities: as long as consumers were getting their ‘efficiencies’, all was dandy.

Even though these ideas were clearly incoherent – for example, dominant firms will (duh!) raise prices if they can, and they absolutely have, worldwide – they were exactly where most Republican and many well-funded Democrat politicians wanted to go. Large firms funded lawyers and academics and lobbyists to imbibe and spread the new creed, which soon infected the courts, the politics and the public conversation. The ideas spread like the Delta variant of COVID-19 – overseas, to Britain, to Europe, and further afield.

Today, anyone who thinks that monopoly is really an American problem, or that the EU’s competition commissioner, Margrethe Vestager, is a monopoly-busting hero protecting Europeans from the giants’ predation, hasn’t been paying attention. While it’s well known that the European Commission has fined Google over $9bn for abuses going back over a decade, that amounts to less than 1% of the company’s trillion-dollar-plus revenues during that period. It’s not even a dent.

Look, for instance, at the current priorities of the European competition regulator, whose Twitter handle explains that it “enforces competition law within the EU for the benefit of consumers”, or Britain’s CMA, which promises to “promote competition for the benefit of consumers”. That is Bork’s influence.

Of course, regulation in the EU and the UK is more nuanced than these statements would suggest, and European social democracy, taxes, fines and regulation have blunted some of the sharpest edges of brute monopoly power. But there is no doubt that regulators have allowed monopoly power to grow, with little resistance.

Out of more than 8,000 mergers notified to the European Commission since 1990, a total of 30 have been blocked – less than 0.4%. The UK has a similarly feeble record. While the number of mergers has risen, the number of cases has fallen – and of that number, fewer than 1% were blocked. Not all mergers are evil, but this is clearly not good enough.

The incoherence of our regulators’ positions can be seen in many areas. Competition authorities do crackdown on cartels, where firms collude, but seem little bothered by mergers, which are formalised, reinforced, permanent versions of cartels. European authorities take aim at “abuse of a dominant position” by large firms, which has its uses. But once a company is dominant, abuse is likely or even inevitable, and regulators must play catch-up, often fighting through courts for years to redress an abuse that may already be obsolete. Better would be to tackle ‘dominant position’ from the get-go, and de-concentrate our markets properly.

A common misunderstanding in civil society is that anti-monopoly is weak medicine. It is weak right now – but only because the Chicago School killed real anti-monopoly. We can reclaim our democracy by strengthening the medicine. And at last, it is being brewed, especially in the United States.

The New Brandeisians

The new American antitrust movement, of which Lina Khan is now the de facto leader, is bringing a radical new story to overturn the Chicago School legacy. Known as ‘the New Brandeis Movement’ to its supporters, or ‘hipster antitrust’ to its detractors, it has set out aggressively to change the public conversation about corporate power.

A keystone of early organising was a 2010 book called ‘Cornered’, by the journalist Barry Lynn. He quoted the Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis in 1926:

The doctrine of the separation of powers was adopted by the convention of 1787 not to promote efficiency but to preclude the exercise of arbitrary power. The purpose was not to avoid friction, but, by means of the inevitable friction incident to the distribution of the government powers among three departments, to save the people from autocracy.

Lynn was joined by others such as Matt Stoller, a pugnacious US writer and activist; Tim Wu, the academic who is now on Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers; Lina Khan; and more recently politicians such as Elizabeth Warren (and now, it seems, Joe Biden). The activists helped catalyse what would become, especially in the past five years or so, a rolling tide of US news coverage and activism around this resonant new story – and now direct access to power. These people attacked Bork’s consumer-focused, efficiency-obsessed ideas, and militated to cut dominant giants down to size by bringing power, democracy, citizenship, and – to use a preferred American term – liberty, to the antitrust debates.

The fruits of this organising include a move in September 2019 by a bipartisan alliance of 50 state attorneys-general to investigate Big Tech, leading to bipartisan lawsuits, which are still ongoing. Last October, the Democrat David Cicilline released a radical blockbuster report on the tech giants; this was followed by Republican Senator Josh Hawley’s Bust Up Big Tech Act last April, then six more bills in June, again with bipartisan support. Then, in July, Biden issued a wide-ranging Executive Order which ranged far beyond Big Tech, and even named and shamed Bork. The Order takes a “whole of government’ approach to corporate power, charging over a dozen federal agencies to implement over 70 anti-monopoly initiatives. As Biden put it: “excessive market concentration threatens basic economic liberties, democratic accountability, and the welfare of workers, farmers, small businesses, startups, and consumers.”

This sudden explosion of activist government, which was hardly visible at the start of this year, represents a stunning reversal of decades of received wisdom embraced by successive Democrat and Republican administrations, that monopolies either do not exist, or are good for us. One can even detect a dry humour in Biden’s anodyne repeated statement that ”this order affirms that it is the policy of my administration to enforce the antitrust laws”, given that several administrations before his, including President Obama’s, rarely bothered with enforcement, let alone serious policy-making. The order even resurrects one of the dirtiest concepts among members of the traditional antitrust establishment – ‘monopsony’ – where dominant firms use their buying power in markets to crush workers and small business suppliers.

The need to ‘reaffirm’ existing governmental powers needed saying – and Biden has even created a White House Competition Council to follow through on the order, and hold regulatory agencies to account. Khan has thrown open the doors of the Federal Trade Commission’s previously closed commissioner meetings, inviting public comment for the first time.

What is striking about the new government activism, apart from its diversity and sheer energy, is how closely it has hewn to a line carved out by the civil society actors, explicitly rejecting the Chicago School ethos. Above all, they want to raise people’s eyes beyond questions of consumer prices and narrow ideas of economic efficiency, and instead view all this through the prism of power: economic power, which rapidly morphs into political and even cultural power, and now threatens the foundations of the democratic state.

These activists, and now increasingly, it seems, the Biden Administration, too – wants to break up giant firms like Google or Facebook or Tyson Foods, with the primary goal being not so much to promote competition (though if effectively regulated that can be a core benefit), but above all to tackle the giants’ dangerous, democracy-bending, economy-shrinking power. Americans’ famous commitment to ‘liberty’, they point out, historically was a bulwark not just against overbearing government, but against private tyrannies such as the great monopolising money trusts run by private financiers a century ago, which gave ‘antitrust’ its name.

This new approach to antitrust is a multi-layered toolkit that goes far beyond breakups. For example, it also wants to stop giants like Amazon selling its own goods on its own platform, or using data they gather to crush economic ecosystems at a flick of their algorithms. Instead, it wants the company to be regulated like a public utility, which it now is. It wants to use ‘interoperability’ and break down ‘walled gardens’ of firms like Facebook or Apple and force them to make data portable (for example: if you hate Facebook’s privacy rules you can use a less damaging platform, yet from there you would still be able to watch dancing puppies posted by your friends who still insist on using Facebook.) It also wants to stop the giants stealing most of the advertising revenues from news organisations, in order to restore local and diverse national news as an essential prop for democracy. It wants to up-end business models that all but guarantee the viral spread of fake news. It wants to cut out middlemen sitting hungrily at choke points where information flows. And it wants to give the antitrust authorities enough resources, and political backing, to govern the economy on behalf of all the people.

These are very early days, and the gains are politically still fragile, with most Trump Republicans taking Big Money’s side. But these are potentially the most ambitious antitrust reforms – and potentially the most ambitious economic reforms – since the 1970s.

The emerging anti-monopoly movement supports pretty much the entire progressive agenda – reining in the power of oversized finance, tackling inequality, protecting democracy, supporting workers, defending local communities against out-of-town wealth-extractors, taking down private equity predation, punishing wealthy lawbreakers, and more. But it also supports many ideals that conservatives are comfortable with too – tackling the corruption of markets, helping small businesses, re-balancing the economy to ‘level up’ left-behind regions, boosting innovation and economic growth, giving opportunity to all, and more. The new movement has meaningful support among Republicans in the US, and now some Conservatives in the UK are becoming interested in overturning the Bork legacy too. This agenda is now up for grabs here, for any political party that wants it. As in the United States, it will prove immensely popular, and hard to oppose.

A rich, wide-ranging attack on monopoly power has opened up in the US, with Big Tech first in the spotlight. But the movement has a far broader range in its sights: from big agricultural firms, aerospace giants, dominant banks, telecoms firms and even cheerleaders. It wants to broaden the focus away from people as consumers, to people as citizens, and as workers. Above all, it wants to revolutionise the story about how to deal with excessive corporate power.

Wake up, Europe

A last astonishing thing about all this is that despite the progress being made in the US, there’s no matching civil society movement in the UK, Europe, or anywhere else. Nothing remotely like it. It is true that there are many isolated initiatives bubbling up, such as a recent demand from 27 German NGOs for Europe to start breaking up big firms; alliances wanting to Make Amazon Pay; and activists seeking tax justice for giant monopolists. Groups are pushing for specific agendas such as on interoperability, privacy and digital rights, and commercial associations seeking to open up the web to protect smaller firms from giants. There’s lots going on, but no coherent, unifying movement.

Competition regulators in some countries are ahead of the activists in some areas. The EU’s Digital Services Act, for example, has a rudimentary spine. The UK’s CMA has recently pushed against some mergers: for instance, it wants to force Facebook to disgorge Giphy, a break-up of sorts (though far less powerful than what Lina Khan’s Federal Trade Commission is seeking) and it seems to want to stop Sony Music from buying a UK independent label, AWAL. But a properly resourced CMA, given the right mandate and political backing, and a modern world view, could transform our economic landscape. For instance, it could stop in its tracks the current Great British sell-off of large parts of our economy to private equity. Private equity is perhaps the closest modern equivalent to the great money trusts of a century ago, and its financial firepower violently distorts markets. But who is pushing for anything like this?

A new movement

Around a year ago, one of the authors of this article, Michelle Meagher, read a 2019 blog by the other co-author, Nicholas Shaxson, which explored the overlap between tax havens and monopoly power. “European civil society is all but asleep,” the article read, arguing that someone needed to set up an organisation, to try and spark a proper anti-monopoly movement, over this side of the Atlantic, to match the activism in the US. We got talking to each other, and resolved to set up an organisation to try and do this. We formally set up the Balanced Economy Project four months ago, and our core goals are to change the weather on monopolies and antitrust: both to wake people up to the immense potential that antitrust has to tackle some of the biggest challenges of our age, and also to help spur a fundamental rethink of the philosophy and tools that our competition authorities are using. We also want to help build a ‘missing infrastructure’ to ensure that concentrated and dominant private power is constantly challenged by those workers, small businesses and citizens most directly affected by it.

We have confirmed through more than 100 interviews with small businesses, trade unions, farmers, politicians, think tanks, bankers, and activists that there exists an enormous gap in civil society – and an enormous opportunity. We don’t need to cut-and-paste what the Americans are doing: Brits and Europeans have different appetites for tax, for personal freedom, for government intervention, or for privacy, than Americans.

But what is needed now is radicalism, a new story and a new movement to change the conversation about what is possible, and to deliver monopoly justice.

Be the first to comment