Most German establishment political parties have turned away from striving for a better society. In recent decades they have become profit-oriented service companies in a billion euro industry: selling laws, permits, public contracts, even protection, as we are seeing in the case of Volkswagen’s diesel defeat device, to the highest bidder. These parties have sold their autonomy and become a consolidated committee to manage the affairs of corporations and the wealthy.

Mathew D. Rose is an Investigative Journalist specialised in Organised Political Crime and an editor of BRAVE NEW EUROPE.

In the middle of August the powerful lobby organisation, the Federal Association of the German Energy and Water Industries (BDEW), whose most potent members are German coal and nuclear power companies, for the first time nominated a leading Green politician, Kerstin Andreae, as its CEO. Previously this position had been given to industry-friendly politicians from the Christian Union, Social Democrats, and Liberal Party. Ms Andreae will be resigning her mandate in the Bundestag to take up the better-paid job.

One might wonder why, after the recent electoral successes of the Greens and their current record position in opinion polls, a Green politician would change sides? The answer is simple: for the money. Not that members of the Bundestag are poorly paid: 10,000 euros per month plus a couple of thousand more in perks. Lobbyists, however, tend to earn much more.

The more interesting question is why Ms Andreae was nominated for the position? Common knowledge tells us, no one spends money without expecting something in return. The Greens, like the other parties, know only too well from experience that political success translates into money from corporations eager to further their interests in government. Since an election upset in 2011, in the German state of Baden-Württemberg, the Greens have led the government there and still do. Previously the Association of Metal and Electrical Industries, whose major members come from the car and weapons industries, had donated large sums yearly to the traditional political parties: the Christian Democrats, Social Democrats, and the Liberals (FDP) – never sparing a cent for the Greens. In the same year as their election success the Greens in Baden-Württemberg began receiving major donations from the association, although its interests have little in common with ostensible Green policy. Because business has been running as usual in Baden-Württemberg ever since the Greens took over power, the donation has almost doubled to 110,000 euros a year.

German political parties from West Germany have always been highly corrupt. A notable practitioner once referred to it as simply “maintaining the landscape” (Landschaftspflege). But there had always been an accompanying political nicety that there should be enough to go round for everyone – according to their place in the pecking order. Most politicians were content to look forward to a relatively modest, but secure, income after their period of active politics, which their generous state pensions guaranteed. Everyone seemed to accept a certain level of illegal contributions to party funding to “oil the wheels” of German prosperity. In 1996 the provocative leftist journalist Werner Raith wrote a book ironically raising this question: “How much corruption does democracy need?”

That changed dramatically in Germany in 1998 with the election of the Social Democrats’ coalition with the Greens under Gerhard Schröder, Germany’s Tony Blair. This is when the traditional corruption of liberal democracy in Germany – through illegal donations to political parties – was compounded by political corruption on a personal level. There were great advantages to this, especially for non-German international corporations. They were no longer kept at bay by the cosy German old boys club consisting of German firms and political parties. Politicians themselves – especially the most influential ones – could now be bought direct to further a firm’s interests. Germany had created its own political service sector. The political parties’ previous concept of relative social equality was jettisoned. Politics became Big Business in a winner take all neo-liberal market.

In Germany these West German political parties have become literally companies, with the sole interest of maximising their revenues and furthering the careers and wealth-accumulation of their managers, such as Ms Andreae. This quest for profit is true not only for the political parties, but for the whole political class: the advisors, public-relations companies, lawyers, academics, media managers, and journalists. They comprise a network that is always in a state of flux as its participants switch from one role to the other, or even occupy several positions simultaneously. That is not to say that all politicians start out as corrupt. There are many who go into politics with ideals. Either they adapt to the business plan, or they themselves become sidelined within their own parties.

A party that wins an election suddenly finds itself invested with greater power. Prime ministers and heads of ministries have the licence to sell the state. Not only does the party prosper financially, so do its leaders. While remunerations from companies are distributed to the parties in real time, they are rarely paid to politicians while they are in office. The absurdly overpaid jobs come afterwards – and the list of these is long and impressive. Other members of the party profit from success as well with appointments to public jobs, government contracts, subsidies, and other rewards.

To fully grasp this system one first has to understand how political parties are financed in Germany – legally and illegally. Decades ago, before the German political parties threw in their lot with neo-liberalism, they were funded mainly by their members’ dues and donations (both tax deductible – in other words highly subsidised by the state). This was of course supplemented by “landscape maintenance” – legal and illegal – by business interests. Still, it was an era in which Germans still believed in democracy and the social and moral values that political parties represented. But as these parties cast in their lot with Neo-liberal interests and followed the money, their credibility rapidly evaporated. In 1990 the Social Democrats had almost one million members: that number could well collapse below 400,000 by the end of this year. Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats have not fared much better, declining in the same period from 900,000 to just under 400,000 today. The average age of members of both of these parties is 60.

This loss of income through fewer members, fewer donations, and fewer votes (because of decreased voter participation and the rise new political parties) has been compensated by the political parties receiving more money from the nanny state. Germany has a state fund that yearly distributes money among the political parties based on the number of votes received in elections. Conveniently the German parliament alone decides on the level of funding. Although the members have always been very generous to themselves, this has now reached new heights. Following the Christian and Social Democrats’ dramatic political decline in the recent past resulting in a reduction of the payout from this fund, in 2018 the parties simply increased the fund by around 20 percent to 190 million euros per year (over 40 percent in the past ten years) – despite austerity. This brought them back to, if not above, what they previously received.

German political parties have plenty of tricks up their sleeve to appropriate more public money for themselves. Most parties expect their members who obtain high public office (be it in the EU, Bundestag, state, or local government) to donate around ten percent of their bountiful salaries to the party. It is odd, as these regularly receive pay increases (usually above the rate of inflation, in the Bundestag about 30% in the past ten years of austerity) with the explanation that they cannot live from their salaries (many of these are over 10,000 euros per month). Then there are the state-financed political foundations, pseudo think-tanks of the political parties, that politicians pretend are independent so that they can receive state funds. This is extremely generous, with 600 million euros per year (also an increase of round 30% in the past ten years of austerity). Not only do they provide jobs and perks for party cronies, but they are an excellent way of recycling public funds back to the parties.

Donations play a dwindling role in party finances. Why should citizens donate to parties that do not serve their interests, although these contributions are highly subsidised through a tax deduction? Donations by companies are also in decline, but for other reasons. First, they do not receive much of a tax deduction. Even worse is the perception that these donations, which eventually have to be made public, are a means for companies to buy favours from the political parties – not good PR.

Companies have found other more subtle ways of gaining traction with politicians, such as renting stalls at party events. A stall at an annual conference is often more expensive than at a major trade fair, although the party conferences are only for two days and have a limited number of visitors. Companies can fully deduct these costs from their taxes as operating expenses, which they cannot do with donations. Better still, they are not transparent, since the parties have stubbornly refused to pass a law so that the names of the companies and the amount they pay are made public. For party members it is not only a free lunch, but a free breakfast, dinner, and booze-up as well, since many of the stalls provide food and drink free – all tax deductible. This is not only the case at annual party conferences, but apparently at almost any party event including celebrations and festivities. It must be said that the Links (Left) party and the ultra-right AfD do not have stalls at their party events and do not partake in this practice.

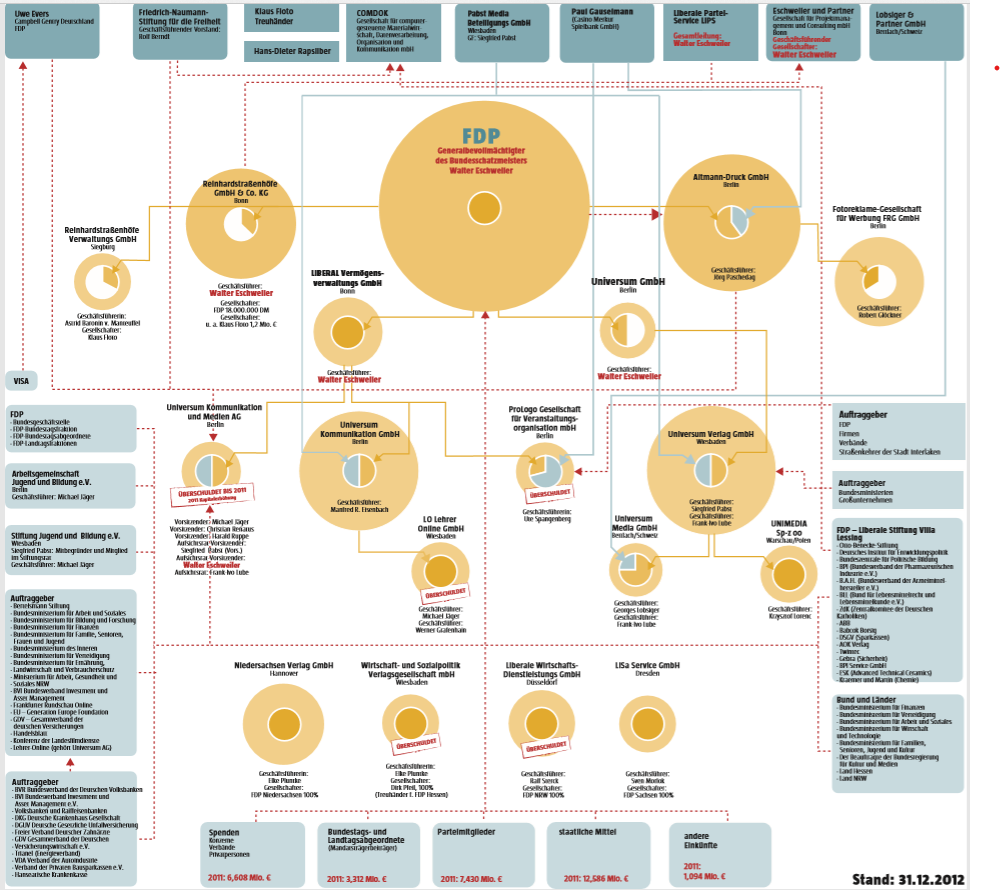

There are other means for parties to acquire millions from corporations without the public ever knowing. The Liberal Party (FDP) built up a conglomerate of firms owned by two holding companies it had created. Very limited transparency is required if a party has not invested directly in a company, which is the case as soon as you insert a holding company in between. This holding empire even had a firm in Switzerland (which was closed down at the same time as laws were tightened regarding tax and currency movements) and in Poland. This is what the FDP holding construction looked like at the end of 2012.

Graphic: Die TAZ/Mathew D. Rose

Interestingly, most of the customers of these firms were either those corporations (all tax deductible) that usually support the political parties through donations or stall-rentals or government ministries where the FDP was influential. The few contracts that came to light had nothing to do with serious business, but look more like they were designed to transfer funds to the party in return for political favours.

One example is the investment by Paul Gauselmann, Germany’s “pope of the gambling arcade business” in firms in the FDP holding company. Not only do Gauselmann’s companies produce slot machines, but he also runs a large chain of arcades in Germany and Europe. Using one of his employees as a front, Gauselmann bought into two almost worthless (maybe worthless) firms of the FDP holding company, a small printing company and a dubious event management. By the time the complicated transactions, which stretched over almost a decade, were completed the Liberals had received round 3.5 million euros from Gauselmann’s companies. As the FDP was in a government coalition from 2009 to 2013, despite public and political pressure to introduce robuster gambling laws for slot machines, the Ministry for Economic Affairs, headed by an FDP minister, managed to avoid this. Hardly were they voted out of office, the law was passed.

As the old political class are learning, theirs is not a risk-free business. For decades most mainstream parties assumed there was no alternative to electing them and that they were thus immune from the consequences of their corruption and greed. Even as voter participation dwindled there was still no real competition. But with the recent dramatic loss in political trust we are seeing parties that were national institutions declining into irrelevancy. With no power, there is no money, no highly remunerated jobs, no invites for luxury “information gathering” travels. No nothing.

This loss of credibility has had an astonishing effect on the public support of the traditional German parties and the political structure of the nation. In September there will be elections in three of Germany’s Eastern federal states. The far-right and ultra-Neo-liberal party Alternative for Germany (AfD), will surely do well – too well – in all of these. If you add this percentage to the non-voters and those voting for other parties, one will discover that Germany’s “centrist liberal democratic parties” (Christian Union, Social Democrats, Liberals, Greens, and the Left Party) can only mobilise round a third of the electorate to vote for them in these states. This is the new reality facing Liberal Democracy in Germany.

The political and media establishment in Germany decry that Liberal Democracy is under attack. It isn’t. It is rotting from its core.

Be the first to comment