There is a pervasive myth about the effects of taxation on a country’s economic growth, namely that higher taxes mean less growth.

Paul Whiteley is Professor, Department of Government, University of Essex

Cross-posted from The Conversation

Krishna and three gopas demand the butter tax

Taxation has turned out to be the main issue dividing the two candidates in the current Conservative Party leadership contest. While Rishi Sunak wants to hold off making tax cuts until after the cost of living crisis has been tackled, Liz Truss wants immediate reductions. She believes cutting taxes will not cause further rises in inflation for consumers.

But setting aside concerns that tax cuts risk accelerating price increases by giving people and businesses more money to spend, these strategies also don’t account for the need to address the current crises facing the UK. In addition to an underfunded health service, households need more help with skyrocketing energy costs this winter. This will require large increases in government spending in the immediate future. Britain will need to pay for this either by borrowing more or raising taxes, not lowering them.

There is a pervasive myth about the effects of taxation on a country’s economic growth, namely that higher taxes mean less growth. It is one of those ideas that may seem plausible at first, but is in fact quite wrong. One of the sources of this myth is the idea that raising taxes reduces people’s incentive to work. Put simply, that people will refuse to take on a new job or accept a pay rise because it means paying more tax. Economists have found this idea difficult to prove, however.

Furthermore, various income support experiments conducted across the world show that raising welfare payments has no effect on willingness to work. And research also shows that tax cuts for businesses in US states have no effect on economic growth.

It is also possible to cast doubt on the myth that higher taxes prevent economic growth by looking at the relationship between tax levels and economic growth in the world’s most advanced industrial economies – the 38 member states of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) – over a long period of time.

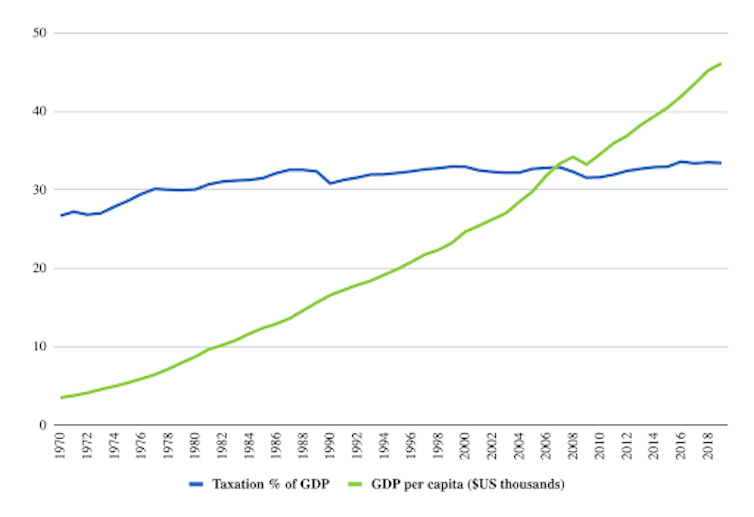

1. OECD taxes rise alongside GDP growth

The chart above shows the levels of taxation (from all sources) and gross domestic product (GDP) per capita among OECD members over the 50 years since 1970. Both GDP (which indicates the size and health of an economy) and the tax take in these countries have increased over time, with the former rising more rapidly than the latter. This produces a strong positive correlation between the two, indicating that higher taxes are associated with increased prosperity, rather than the opposite.

For example in 2019, the last year before COVID hit the world economy, the GDP per capita figures in Germany, Sweden and Denmark were respectively 13%, 11% and 17% higher than in Britain – despite all three countries having significantly higher tax rates.

The simple explanation for this is based on the interaction between growth and taxation. As countries grow richer, they can raise taxes and spend more on education, health, welfare and other public services. At the same time, this stimulates growth because investment in infrastructure and a healthier and more educated work force increases productivity.

In contrast, reduced spending means less investment and ultimately lower productivity and growth. The way to stimulate growth is to invest in both private and public assets at the same time, rather than by impoverishing public investment in the mistaken belief that this will stimulate private investment.

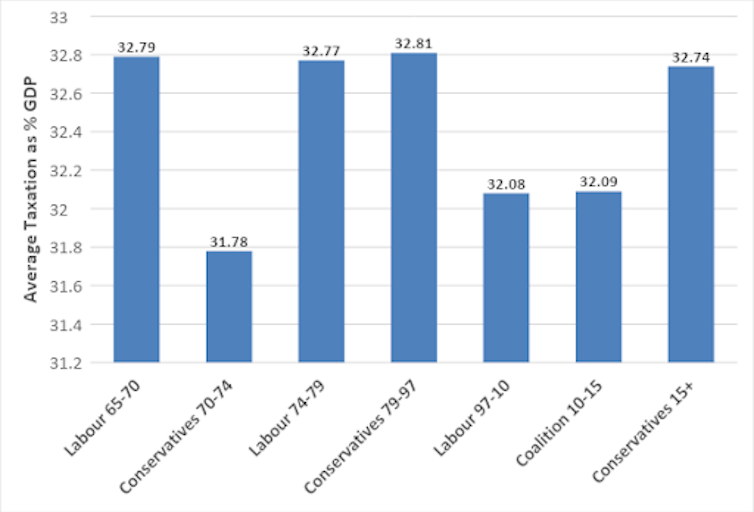

While the vast majority of OECD members have raised taxes over the last 50 years, Britain has not. This can be seen in the chart below, which shows taxation as a percentage of GDP in Britain since the start of Harold Wilson’s Labour government in 1965. Britain’s current tax take is essentially the same as it was more than half a century ago, while taxes have increased by about 25% across the rest of the OECD.

2. UK taxes as a percentage of GDP

The chart also shows that there is little difference between successive British governments and the size of the tax take over time. There were fluctuations, but they were quite small and unrelated to which party was in power. This highlights Britain’s collective problem of “cakeism” – that is, wanting decent public services but being unwilling to pay for them. Part of the reason for this is that both major parties appear to be unwilling to tell the public the truth: we can’t cut taxes and address current crises in the cost of living and public services without borrowing more.

Addressing crises while avoiding a crash

So many of our public services are currently in crisis – whether it’s crumbling hospitals, a chronic shortage of NHS staff, the risk of social care system collapse, or even roads full of potholes. In the end, all of this comes down to a lack of spending and investment.

Ramping up borrowing further is not a long-term solution to this problem. In the last few years, international borrowing by Britain has mushroomed in size. In March 2022 it was £2,365 billion, or just under 100% of GDP – a much higher proportion than in the past, and an indication that the UK could already struggle to repay its debts. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and Brexit have all contributed to this.

The interest payments on such borrowing are now rising fairly rapidly as central banks around the world raise rates to combat inflation. This means a government that funds tax cuts by borrowing more is going to risk higher inflation and an accelerating deficit as a result. This is a recipe for an economic crash. Extra spending has to be financed. To do this, Britain needs higher taxes not tax cuts.

Support us and become part of a media that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over.

Clearly this chap is not a fan of, or has never heard of MMT. Sovereign governments do not need taxation to fund their spending. When will this message get through some people’s thick heads? Mr Whitely should speak to Steve Keen, or Bill Mitchell, or Richard Murphy, or any number of other heterodox economists, and perhaps even ex-Bank of England head Mervyn King. Of course Truss and Sunak could/should do the same, but then they have political agendas (as did Osborne) that are not about the welfare of British people but rather about further entrenching their neo-liberal ideology – so use of fiscal capability is probably out of the question.