The starting point for this overview of the European response to Covid is France and the UK but the lessons drawn have universal applicability not only for future Covid and pandemic management but governance of wider concern.

Roger Steer is a Management Consultant working in the Healthcare sector as well as an Advisor to Local authorities scrutinising NHS plans. He is based in France but active in the UK.

The history of pandemic management

Pandemics and communicable diseases, vaccines and public health measures designed to deal with them are nothing new. It is commonly understood managing pandemics relies on collection of data, identifying sources of infection, contact tracing, isolation of the infected, closures of transmission routes, and eradication of the means for a pandemic to spread. Vaccines in the meantime were developed to assist healthy bodies build defences to resist infection and for immunity to spread amongst populations; though in the case of smallpox an effective vaccine was never enough to defeat and eradicate the disease, and in the case of seasonal flu, vaccines must evolve as the virus evolves.

Differing approaches within Europe to the common problem

Thus, in confronting the Covid pandemic the knowledge and means for managing a pandemic were well understood at the outset. Indeed, a future pandemic was identified in the UK in a national risk assessment as the biggest risk faced. A future pandemic was war-gamed as Exercise Cygnus in 2016. Key deficiencies were drawn to the attention of government ministers. Unfortunately these ministers had other things on their plate (Brexit perhaps), didn’t get round to learning the lessons, and actually ran down stocks of PPE as an economy measure .

In other words the UK was let down by its leaders who failed to heed advice, failed to prepare for a predicted threat (though some people in the pharmaceutical industry evidently did), and continued to fret about government debt rather than prepare for the future. The UK introduced emergency legislation but seems to have followed a tradition of botched innovation to recover the situation.

France seemed equally unprepared; a recent public consultation on environmental hazards was preoccupied with issues like the hazards of 5G and blue light rather than the risks of pandemics. It seems the role of monitoring communicable diseases was allocated to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

This is discussed by Audrey Lebret in “COVID-19 pandemic and derogation to human rights”, who reminds us the EU does not have competence in the field of Public Health. In her conclusions Lebret predicts a future flood of cases for Human Rights courts, and asserts “this crisis shows the fragility of health systems, urging governments to review their strategies and to (re)invest massively in the healthcare sector”.

By achieving Brexit the UK government feels it can ignore such pan-European concerns, and will not change its plans for the NHS; it will continue to rationalise, to force higher productivity from fewer beds and fewer staff. Moreover it has taken the opportunity of granting of special powers to itself to overturn laws governing public procurement and granted billions of pounds of contracts to cronies under cover of emergency and pushed back the consequences of Covid onto nursing homes and the sick and elderly.

Different baselines within Europe

Europe is far from homogenous. The health and social care resources, capacity and staff available vary considerably between nations 12 but also crucially there are huge differences in housing, labour market structure and resilience, industrial capability and investment in relevant technological support, and ability to borrow and ride out the economic consequences of lockdown.

Added to that are significant differences in the level of trust and confidence that population have in governments and in the levels of good governance practices and corrupt practices within governments. For each of the factors mentioned above there is a spectrum of current bandwidth available to respond, and a further spectrum of options of how to respond.

How the UK faced the crisis

The UK has a depleted and under-resourced capacity in its healthcare and social care systems compared to other large European countries but it has large and capable pharmaceutical, biotechnology and university sectors enabling it to mobilise resources to take advantage of historical investment in vaccine research and production. In addition the UK lacked indigenous PPE and a national Test and Trace system (TAT) capable of mobilising quickly enough (even now it cannot cope).

It also has physically smaller houses making it more onerous to impose long-term lockdown conditions. Labour laws that give workers fewer rights and less protections than in Europe generally also mean that workers have not been able to self-isolate as readily if they suspect infection, for fear of losing income, and it has been easier to push the burden of Covid onto the low paid, self-employed and those on basic benefits

Secrecy and a highly centralised management of public messaging has also undermined confidence and generated mistrust as to whether everyone was being treated fairly and equally.

How France faced the crisis

The French government was more explicit that it was following classic logistical practices in managing the pandemic and its uneven impact. Gilles Pache describes the position faced by France and explicitly states the choice France made to manage the situation. He highlights both that France had 7.5 intensive care beds per 100,000 population compared to Germany’s 29 beds per 100,000 population (England and Wales was 7.3 as the pandemic broke) and that it sought to manage the situation by smoothing demand, outsourcing capacity and investing in additional capacity. Lockdown was the route taken to smooth demand, and bringing back into the public sector, private intensive care beds and transferring patients in hotspots to less intensively pressured parts of France, was the other main tactic used. The strategy of building extra capacity was minimal in effect as it was seen not to be consistent with the lean policies pursued up to that point.

President Macron adopted the mantle of responsive and effective manager of such a strategy in contrast with the half-hearted and ambivalent strategy of Johnson in the UK. This meant that France took a lead in announcing lockdown in March 2020, imposing a more restrictive version than in other countries and was quicker to retighten restrictions after the disastrous summer relaxation (which would be good if effective, but it still stands as ineffective compared to the more successful strategies adopted in China, South Korea and Taiwan).

This is not an international competition to show who is a better manager of Covid but a battle to prevent and control a pandemic about which the daily death count tells its own story and in which the well-prepared Far East (who had already suffered the SARS epidemic) has performed much better.

Differences in data, information, scientific advice-giving and decision-making

France has better website-based public information providing more data drawn more locally (for example that informs people of the capacity and occupancy of intensive care beds); but they have not done the genomic analysis that identified the new variant or pursued such a long-sighted industrial strategy; they had supported the EU strategy of pooled purchasing of Covid vaccines without taking particularly aggressive steps as a nation. One thing the French have been spared however is the passive/aggressive spectacle of advisers appearing alongside politicians. Instead in France there has been clear responsibility taken by politicians who have been able themselves to convey in detail the public health messages. There is a national public health body but it appears to have a low profile.

The contrast between France and the UK is therefore between nations with differing levels of capacity (UK bad, France better), similar levels of preparedness (both poor) but the UK enjoying a lead in vaccines and in its industrial preparedness to mass-produce vaccines (even the French vaccine is a joint venture with the UK’s GSK). Test and Trace has been largely ineffective in each country but whereas Macron has ensured a lid has been kept on the rate of infection, Johnson has preached personal responsibility and over-optimism (a deadly cocktail as it turns out with the death rate twice as high in the UK currently). But the key difference appears to be ideological with France seeing it as an opportunity to promote an integrated European response (possibly to shift blame as in law competence rests with the nation) and the UK keen to do its own thing, in its own way, reflecting the personality of its leader (bumbling, over-optimistic, and ‘made in Britain’).

On governance and quality of decision-making France has been quick, responsive, decisive and relatively open, engaging and clear in communication of messages. The UK has again in contrast been dithering, indecisive, conflicted and with a tendency to secrecy, dictate and U-turns. That said, good luck and misfortune may have also played a part. The UK as an island had additional time to prepare (which was wasted) and also GSK (and its predecessor bodies) had invested in vaccine development. France on the contrary was plunged into crisis by a super spreader event in the early period that caught its services ill prepared (although with better capacity and stocks of PPE).

Management of the economic consequences of the pandemic

France and the UK had different starting points but shared a common outlook. Both Macron and Johnson support the common nostrums of neo-liberalism (economic stringency, shrinking the state, support for further privatisation); both are also nationalistic, keen to promote local champions in the industrial race; and prepared to make opportunistic policy changes if that helps their own position. They differ over Europe with Macron seeing it as a way to achieve French goals and Johnson seeing European goals as inconsistent with the Singapore-style UK he favours.

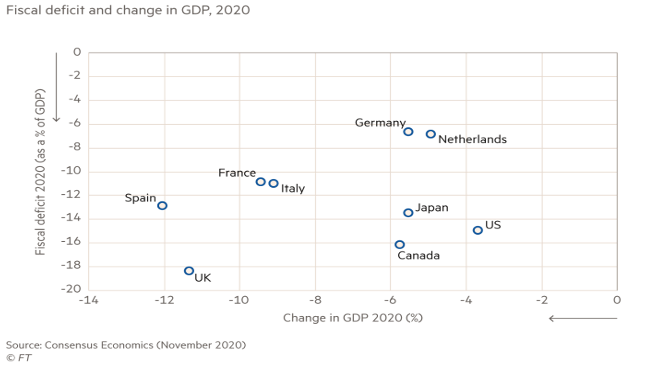

Chart 1. The relative impact on GDP on major countries from Covid

This chart shows the relative impact on the major economies of the pandemic: France and the UK are at the back of the pack on both falls in GDP and Budget deficit.

Leading economic commentators have grave reservations about the way the UK government is managing the crisis. Richard Murphy for example is predicting a bloodbath for companies in 2021 as cash runs out and government funding and support tapers.Others have pointed to very low levels of unemployment and welfare support in the UK exacerbating the impact of the recession.

Fortunately the world has moved on since 1929. World governments, with the help of Ben Bernanke and Gordon Brown, reacted appropriately to the 2008 financial crash by helping to sustain demand and confidence. Similar measures are being taken this time round with Central Banks across the world extending money creation to support governments in providing temporary support to economies during the pandemic. Developments in expressing a theoretical basis for this (Modern Monetary Theory) have helped deflect needless worries about the debt created and the ability of economies to manage the consequences (The Deficit Myth. Modern Monetary Theory and How to Build a Better Economy, Stephanie Kelton, 2020). Others have identified that future costs associated with increased costs of health and social care, climate change, pensions, public infrastructure and income support are manageable and affordable (Bigger Government, Marc Robinson, 2020).

Comparing again the French and UK economies, both have fared badly, with France slightly better. The risk for France is that the EU Central Bank (ECB) will not be as effective as the Bank of England (BOE), hampered as the ECB is by German economic orthodoxy.

Conclusion

- Preparation saves; complacency kills

- Efficient mitigation helps but an effective vaccine rescues

- Surveillance state may have arrived, and may be necessary for longer term control purposes of this and future pandemics

- Economic costs of the pandemic are huge, unfairly distributed, but manageable for society

- The State is good, is powerful, and has the tools to lead, in co-operation across the planet, to a partial restoration to normality.

- Capacity of health and social care systems must be improved and market barriers to essential investment in climate change, infrastructure and job creation must be overcome.

- Good may therefore come of this. It has clarified priorities and shown that it is possible to overcome problems if resources are applied properly. The power of new medical techniques available for the common good has been demonstrated and this should continue instead of the erstwhile gradual development to maximise profits and rental opportunities.

- Economic systems and tools must be developed to create incentives for effort and performance toward the right goals and to avoid capture of technological innovations by profit maximisers and rentiers paid by restricting access and over-pricing.

Be the first to comment