Following years of neo-liberal regimen under the right-wing Partido Popular under its leader Mariano Rajoy, the social democrats (PSOE), led by Pedro Sánchez, are now under pressure to reverse these policies, something that they appear to be doing half-heartedly, explains Sergi Cutillas. With a minority government, the Social Democrats will have to make some serious concessions to gain allies in Spain´s current complicated political landscape, which seems to be causing them some difficulties.

Sergi Cutillas is an economist and worked in the financial sector before taking up his work as a financial justice activist in early 2012. He is a member of the European Research Network on Social and Economic Policy. He is now Secretary of Economy and Work in Podemos Catalonia.

Cross-posted from Makroskop (German)

Translated from Spanish and edited by BRAVE NEW EUROPE

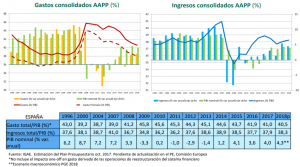

Spain’s public revenue stood at 37.9% of GDP in 2017 and is forecast at 38.3% in 2018, a figure that is clearly below the average for the European Union (44.9%) and EU nations such as Germany (45.2%) and France (53.9%). Public spending in Spain is also below the EU average. Specifically, last year it was 41% of GDP compared to 45.8% on average in the EU, and in 2018 is expected to drop to 40.5%, which would meet the deficit target agreed with Brussels of 2.2%, an objective that the new government of Pedro Sanchez already sees difficult to meet.

So far the decrease of the deficit has been achieved by a reduction in public spending (2010, 2011, 2012, 2016) or an increase always below the increase in nominal GDP (2013, 2014, 2015, 2017, 2018), which has reduced the weight of expenditure in relation to GDP from 45.8% in 2009 to 41%, combined with a modest recovery in the weight of revenue from 34.8% to 37.9%.

If we look at consolidated spending the figure is a little lower than the percentages of spending in relation to GDP cited by the Ministry of Finance, being 449,787 million euros by 2018, approximately 6,650 million higher than the 443,136 million in 2017, representing a 1.5% increase in spending, while nominal GDP will grow by 4.3% in 2018.

Consolidated Spending Consolidated Revenues

With this poor outlook, many expected Sánchez’s new social democratic government to turn a new page with his 2019 budget, with a political strategy completely different from that of its predecessor, the neo-liberal Partido Popular, which insisted on placing the reduction of the deficit above the rest of its objectives, mainly through a reduction of public spending. This reduction in the deficit, despite having been carried out much more slowly than initially planned in 2012, when Rajoy could gain Merkel’s support to relax Spain´s consolidation policy, has meant that fundamental needs for the country in terms of services and public investment have ceased to be met, once again drifting below the European average.

Above all, it must be clear that the reduction of the public deficit, in a period in which the private sector is in a phase of saving/debt reduction (the Spanish business sector is one of the most indebted in Europe) and when unemployment is still very high, has no other macroeconomic sense than to consciously harm domestic demand, in order to reduce the competitiveness gap that Spain has with Germany, thus cutting down the trade deficits with Germany. All this was done in order to keep us within the eurozone and save the banking sector, which needed subsidies and stability to restore its balance sheets. Without the euro, a country that had its own currency (not like the countries of the south of the eurozone that currently operate de facto with a foreign currency contrary to their interests) Spain, Italy, Portugal and Greece could adapt their public balance sheets to the indebtedness or savings needs of the private sector. Moreover, without the artificial restriction of the fiscal pact of the eurozone, the Spanish public sector could set in motion a development plan aimed at achieving full employment and initiating the energy transition, an impulse to which the private sector would soon be added, taking into account the productive capacity and idle work force that currently exist in Spain.

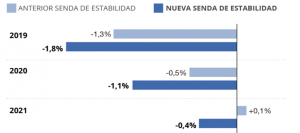

As expected, the government of Pedro Sánchez appears not willing to take such a bold course with the deficit. In fact, in what was perhaps the most important part of his speech during the motion of censure that toppled Rajoy, Pedro Sánchez accepted Rajoy´s planned 2018 budget, and made it clear that his new government would devote body and soul to bringing stability, while meeting the deficit targets set by the EU. However, many, naively, expected more from the July negotiations between the government and Brussels, which had the objective of relaxing the deficit. A change in the deficit regimen that arose from such negotiations was nugatory, the new objectives continuing in Rajoy’s footsteps and in accordance with the neoliberal institutional apparatus established in the Stability and Growth Pact, and later deepened during the crisis with the Fiscal Pact (2012)

Previous Stability Plan New Stability Plan

Judging from the result, since taking office it does not appear that the Sanchez government has adopted the ambitious and daring attitude towards deficits that it conveyed to the public. In fact, the Independent Fiscal Responsibility Authority (AIReF), an independent institution that supervises public finances and was created at the initiative of the EU, in its own reports contemplated that Spain’s deficit for 2019 would reach up to 2.2% if policies remained constant, and the European Commission itself already contemplated in its most recent reports a deficit of 1.9% for 2019, so that the government returned from the negotiation not only without having obtained concessions but also with duties to continue with fiscal adjustment in order to reach 1.8% in 2019.

Airef’s estimates with constant policies

Total Public Expenditures Capacity/Necessities Financing 2018-2019

It would be harmful for our economy to continue to deepen the fiscal contraction until surpluses are achieved, as dictated in the 2012 Fiscal Pact, which is an agreement that only serves the German export elite to impose their mercantilist vision in the eurozone. Spain is confronted with very critical economic and social challenges, such as increasing spending on fundamental public services and putting in place a development plan for the energy transition that helps to guarantee employment for those who want to work and that takes advantage of idle productive capacity. On the other hand, the objective agreed by the government with Brussels would oblige that part of the increased state revenues could not be used to reverse expenditure cuts of the previous government and boost public investment, instead being used to achieve a deficit objective that is a harmful fetish to the interests of Spain´s working people.

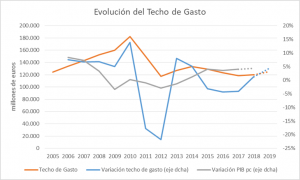

Such deficit targets are the basis for the proposal for a ‘spending ceiling’ of 125,064 million euros, which was presented to the Congress of Deputies for approval as a first step to be able to initiate the budget debate. The ‘expenditure ceiling’ is an instrument included in the Budgetary Stability and Financial Sustainability Law (LOEPSF) of April 2012 (the law that transposes the modification of article 135 of the Constitution made by Zapatero in August 2011, which establishes as a priority the payment of the debt over any other public sector expenditure, as well as of the European Fiscal Pact of 2012. The law states that “the limit of non-financial expenditure is an instrument of budgetary management through which, once the income for the year is estimated, the budgetary expenditure is calculated to permit compliance with the objective of stability”. The ceiling for 2019 would be 5,230 million euros more than in 2018, but 55,000 million less than in 2010.

Evolution of spending ceiling

The most recent reference to the intentions of the PSOE in tax matters is contained in what they called an ‘Alternative Budget’, a proposal made when they were in the opposition during the debate of the 2018 budget prepared by the then Finance Minister, Cristobal Montoro. This document contemplates a tax increase of 6,500 million to cover an increase in social spending of 8,000 million (0.6% of GDP). In turn, the 1.5 billion difference would be compensated by fighting fraud and savings provided by the lower interest on the debt. We will have to await the final 2018 deficit (remember that the target is 2.2%) to see if these extraordinary revenues really can be devoted to social policies or must be partially utilised to reducing the deficit to 1.8% (if the deficit of 2.2% is met in 2018, which is considered difficult, it would take a reduction of 0.4%, about 4.7 billion euros to meet the 1.8% target of 2019. Therefore any increase in income that exceeds this 0.4% of GDP could to be used to regain ground in social policies). In this sense, the new government has announced that during its term of office until 2020 it intends to increase its revenues with the following measures:

- Increase in the tax on car fuels: currently the special tax on petrol is 40.25 cents per litre and on diesel 30.7 cents. According to the government, the collection foreseen with this measure would be 2,140 million euros.

- Higher Personal Income Tax: the maximum state rate (the Autonomous Communities have jurisdiction over the other half of the tax) is 22.5%, but in the economic document presented in the opposition as an alternative to the 2018 General State Budget the social democratic party proposed a rate of 26.5% for incomes above 150,000 euros, which could raise an additional 400 million euros.

- Increase in the tax rate on savings (interest, dividends, etc.) for taxpayers who obtain more than 50,000 euros from savings and total income in excess of 150,000 euros, the impact of which would amount to 1,500 million euros.

- Modification of corporate tax: introduce a minimum taxable base of 15% of the accounting result of multinational companies, and calculated that raising the base could increase collection by 4,000 million (corporate tax is the only one of the major tax figures that has not yet recovered to pre-crisis levels. In fact, in 2017 it reached 23,143 million in revenues, far from 44,823 million in 2007).

- Fight against fraud: the government estimates revenue for the Tax Authorities of about 1,500 million euros in the first year.

- Google tax: here the goal is to collect 600 million, although tax experts warn that it will be difficult to raise more than 300 million in one year.

- Tax on banking: with the aim of raising additional revenue of 1,500 million annually, the Treasury is considering imposing a tax on banking, to pay pensions.

These measures, even if they go in the right direction, are insufficient to finance the needs of Spanish citizens and the Spanish economy, given the limitations mentioned above due to the lack of financial and monetary sovereignty. Therefore, despite the fact that the music of the new government sounds good, for the moment the lyrics are not convincing.

It is for this reason that on July 27 Congress voted to reject the spending ceiling presented by Sánchez’s social democratic government. It should be noted that the last word was in the hands of Partido Popular due to the absolute majority that they have in the Senate (upper house), should Congress (lower house) ratify a spending ceiling. Given the conservative bias of the Senate, the only way not to depend on the Partido Popular to agree on a deficit target, which would be to modify the LOEPSF in Congress. This required Sanchez seeking the support of the forces that helped drive Rajoy out of government and replaced him with Sánchez. Given that Sánchez’s social democrats did not contemplate this as a first option, it is clear that its proposal was aimed at appeasing the conservative forces of Spains two neo-liberal right-wing parties, the Partido Popular and Ciudadanos. It is for this reason that the forces that supported Sánchez in the motion of censure of Rajoy: Unidos Podemos, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya -ERC- and Partit Demòcrata de Catalunya –PDeCAT, abstained in this vote, and the Popular Party and Ciudadanos voted against it. This was the first clear demonstration of weakness of the government that seemed to have second thoughts when it came to negotiate with the forces that supported it, since it probably considers that in the eyes of the majority of Spaniards it would be prejudicial to negotiate with the Catalan pro-independence political forces, as well as to make too many concessions to Unidos Podemos. Since then relations have improved somewhat and PSOE and Unidos Podemos reached an agreement to change the LOEPSF in order not to depend on PP’s support in a Senate vote, and to reverse the cuts that were applied by the Partido Popular in education, health and welfare.

Admittedly, the search for the support of the forces that voted in favour of the motion has become complicated since Puigdemont, former president of the Catalonia who declared its independence unsuccessfully in October 2017 and had to flee to Belgium so as not to be imprisoned, has taken control of the PDeCAT at its latest party congress at the end of July. His first action was to relegate PDeCAT members that facilitated Rajoy’s exit by voting in favour of the censure motion in Congress. Puigdemont, unjustly accused of rebellion by the Spanish Supreme Court, has a personal and electoral interest in maintaining some tension between the Spain and Catalonia, so it will not be easy for Sánchez to gain Puidgemont’s support to pass his budget.

Sanchez’s first major defeat could be an indication that his government cannot, and perhaps will not, last. One possible strategy, if he does not obtain support for the budget this autumn, would be to call an early general election, perhaps to coincide with the European, municipal, and autonomous elections of May 2019, taking advantage of the fact that the latest polls placed Sánchez’s social democrats in the lead with 29% of the votes. If so, next May will be a decisive date for Spain’s political future. In any case, Spaniards deserve a government that does not engage in electoral tactical games and that is committed to developing budgets to reverse the cuts, eliminate unemployment, reduce inequality and promote a change of economic and energy model, budgets that are consistent with the enormous challenges facing Spaniards for 2019.

Be the first to comment