Where there is debt, there are assets. One cannot exist without the other

Steve Keen is a Distinguished Research Fellow, Institute for Strategy, Resilience & Security, UCL

Cross-posted from Steve’s website Patreon Website

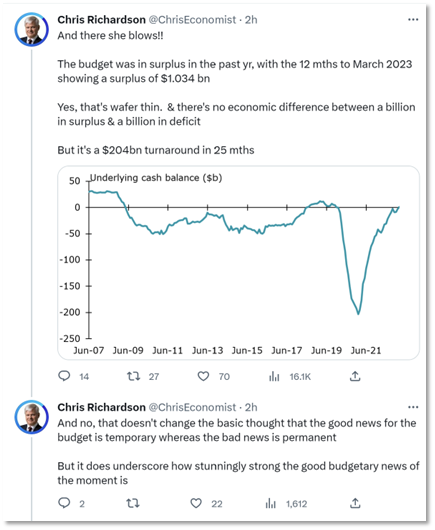

The prominent Australian mainstream economist Chris Richardson recently celebrated the fact that the Australian government is now in surplus:

His “temporary” and “permanent” comment was in relation to this earlier tweet: tax revenues are up but that’s temporary; there’s too much spending, and that’s permanent.

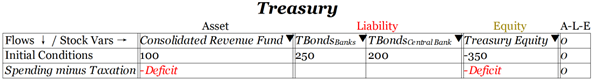

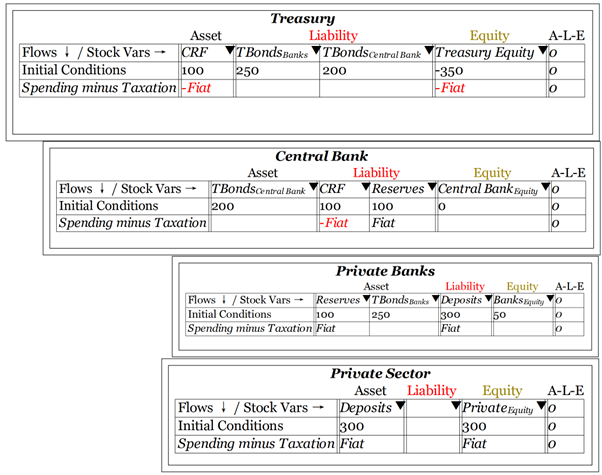

Yes, this is “stunningly strong” news for the government’s finances, seen in isolation. Figure 1 shows this situation. If the government spends more than it gets back in taxation, then it runs a deficit. The deficit reduces the amount of money in the Treasury’s deposit account at the Central Bank—the “Consolidated Revenue Fund”. This means that the government, which already has more liabilities than assets—and is therefore in negative equity—is pushed even further into negative equity. That has to be bad, right?

Figure 1: A deficit pushes the government further into negative equity! BAD BAD BAD!!!

Sure, if you take a partial view of the financial system, and look just at the government’s accounts in isolation. But that sort of thinking is something that economists, in other circumstances, deride as “partial” analysis. What you really need to do, to truly understand a system, is do a general analysis—and that means looking at the entire system. In the case of government deficits, that means looking at the accounts for the Central Bank, the private banks, and the non-bank private sector, as well as for the Treasury.

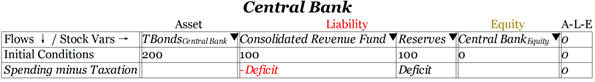

The “Consolidated Revenue Fund” (CRF), which is the Treasury’s asset, is the Treasury’s deposit account at the Central Bank: it is a liability of the Central Bank, just as your deposit account at a private bank is your asset and the private bank’s liability.

The private banks also have accounts at the Central Bank, which economists call Reserve accounts. When the government runs a deficit, the CRF falls and the Reserve accounts of the private banks rise. This is a necessary step in how the government’s spending and taxation affect the private sector’s bank accounts. This transfer of funds from the Treasury’s Consolidated Revenue Fund to the Reserve accounts of the private banks is shown in Figure 2—where I’ve replaced the wordy “Consolidated Revenue Fund” with its abbreviation CRF.

Figure 2: The Deficit transfers funds from Treasury’s CRF to the Reserve accounts of private banks

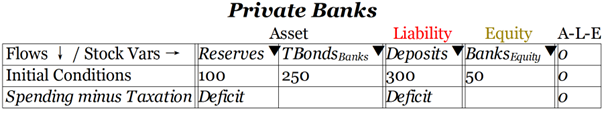

The increase in Reserves caused by the Deficit enables the private banks to increase the non-bank private sector’s deposit accounts—which is what a deficit does. A deficit occurs when the government spends more on the private sector than it takes back from the private sector in taxes. A deficit therefore increases the money supply, by increasing the private sector’s bank accounts. This is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: The Deficit increases bank Reserves and the private sector’s Deposit accounts

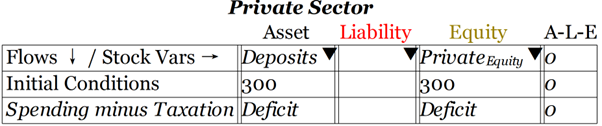

Finally, the Deficit increases the private non-bank sector’s net worth: the increase in the value of the private sector’s Deposit accounts doesn’t come with any offsetting increase in the private sector’s liabilities, so the net worth of the private sector rises. This is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4:The Deficit increases the private sector’s Assets without changing its Liabilities, so the net worth of the private sector rises

So, what is a negative for net worth of the government—when it runs a deficit—is a positive for the private sector. When the government decreases its net worth by running a deficit, it increases the net worth of the private sector by precisely as much. A deficit for the government is a surplus for the private sector.

What is Richardson really celebrating, because the government is now running a surplus? He’s celebrating the government reducing the financial resources of the private sector. He’s celebrating the government reducing the money supply. Somehow, this is supposed to make the economy work better.

I deliberately haven’t considered the government debt issues in this post, because I want to focus on the core point that a government Surplus, while it increases the net worth of the government, necessarily reduces the net worth of the private sector. I’ll cover the government debt issue in my next post, but I hope this one points out something ridiculous in celebrating the government running a Surplus: you are also celebrating the private sector being forced to run a matching Deficit.

Finally, though Richardson’s celebration of a government surplus is typical of the flawed, partial analysis that mainstream economists do when they attempt to analyse the monetary system, it’s also, I think, a product of the pejorative nature of the words “Deficit” and “Surplus”.

A Deficit is BAD! A Surplus is GOOD!

Really? Not when you take a systemic, rather than a partial, look at the financial system. Then a Deficit for one sector is a necessary consequence of a Surplus for another sector: you can’t have one without the other.

Frankly, I’m so sick of this flawed partial thinking that I refuse to use the words “Deficit” and “Surplus”. I will instead use the word “Fiat” to describe a government “Deficit”, because what this so-called Deficit does is actually create “Fiat” money, while a government Surplus destroys Fiat money.

In my next post, I’ll complete the “debt” side of this model. In the meantime, I’ll await an explanation from Richardson of why it’s a good idea for the government to destroy Fiat money.

Figure 5: It’s not a Deficit, it’s a Fiat

Be the first to comment