Excessive inequality and wealth redistribution to the rich have wrecked the economy. ‘Trussonomics’ won’t help

Stewart Lansley is author of the The Richer, the Poorer: How Britain Enriched the Few and Failed the Poor (Bristol University Press). He is a visiting fellow at the University of Bristol, a council member of the Progressive Economy Forum and a fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences

Cross-posted from Open Demcoracy

Photo: Simon Dawson licensed under the United Kingdom Open Government Licence v3.0

Our new prime minister has already set out her primary economic principles. Although a £90bn bailout to help households and businesses cope with the energy crisis looks on the cards, Liz Truss has made it clear that “handouts” are not her preferred way.

Truss has little option but to make a bold move to prevent a catastrophic fall in living standards. But she has also publicly rejected the idea of looking at the economy through the “lens of redistribution”. By this, she means she is dropping any idea of tackling inequality. Instead, growth will be given priority “because that benefits everyone”.

Both of these declarations show a complete lack of understanding of recent and past political history.

They are a repeat of the arguments used in the 1970s by the anti-egalitarian school of ‘New Right’ evangelists. One of those evangelists, Keith Joseph, a close adviser to Margaret Thatcher, claimed that ‘true’ Conservatives need “to make the case against egalitarianism… The pursuit of equality has done, and is doing, more harm, stunting the incentives and rewards that are essential to any successful economy.”

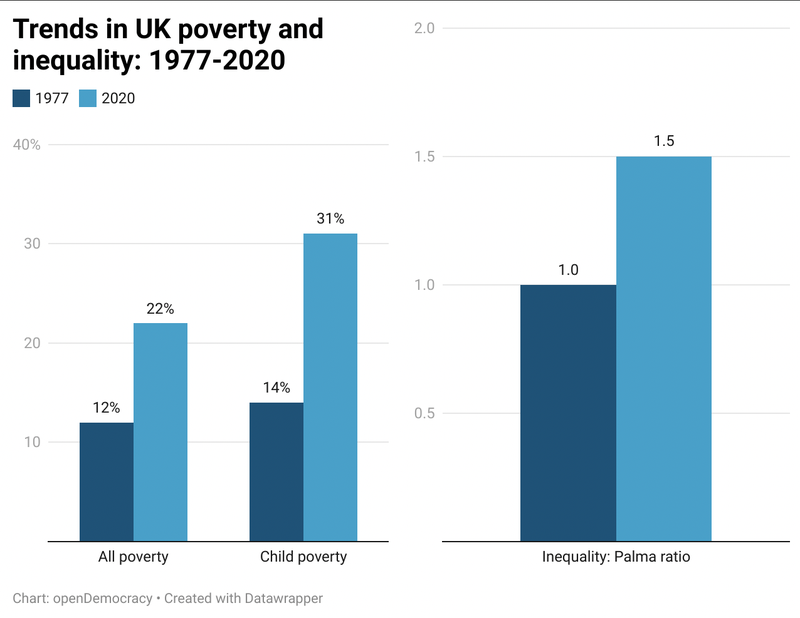

More than 40 years on, we now have the hard evidence from the inequality-driving real-life experiment. Far from benefiting everyone, Britain has been deliberately shifted from being one of the most equal of rich nations to the second most unequal (after the United States). Over the same period, the child poverty rate, in relative terms, has more than doubled (chart 1).

Chart by openDemocracy. Source: Institute for Fiscal Studies

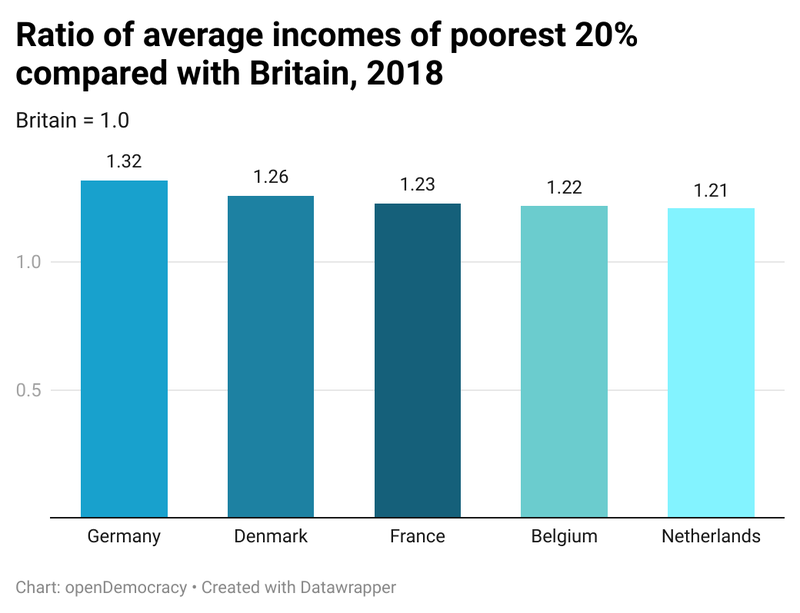

Because of the impact of inequality, the poorest 20% in Britain today are much poorer than their counterparts in other, more equal nations (chart 2). The poorest people in Germany, for example, are a third better off than those in Britain.

Chart by openDemocracy

Truss says we should drop the “lens of redistribution”, but the last 40 years have actually seen a steady process of state-driven redistribution – but upwards, in which the gains from growth have been colonised by a small financial and corporate elite.

Much of this process of towering enrichment at the top has been through a process of extraction, in which companies have been turned into cash cows for executives and shareholders (through, for example, anti-competitive devices to rig markets; excessive fees on financial products; and by diverting rising profits from wages and investment to dividends).

This process has been accompanied by a range of pro-inequality state policies, from the introduction of a much more regressive tax system and the deregulation of state controls over the City and big business to a much meaner and more coercive benefits system. In the mid-2010s, five million sanctions (essentially fines) were issued by the Department for Work and Pensions – that’s more fines than the criminal justice system.

Excessive inequality, low growth

The political licence to get rich, along with the weakening of state social protection, was meant to create a more dynamic economy. Yet growth, private investment and productivity levels have all been lower since 1980 than they were during the post-war era of welfare capitalism. Financial crises have become more frequent and more damaging.

The claim that high inequality was essential for faster economic progress was powerfully exposed by the 2008 financial crisis. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has shown that high levels of inequality are associated with brittle economies that are prone to crisis and weak growth.

y elements of Britain’s economic model – structural poverty, insecure employment and a low wage share – have created consumer societies with a limited capacity to consume and thus a growing dependency on debt to survive.

Excessive inequality is not just economically “corrosive”, as Christine Lagarde, then head of the IMF, put it in 2013. It has also left a growing trail of social distress. The government’s Levelling Up White Paper is a remarkably frank account of Britain’s stark social fragility (even if the strategy to tackle it fails to live up to the scale of the problem identified).

The long improvement in rates of life expectancy has stalled over the last decade and has even been falling in some deprived communities. Political alienation is widespread, with a rising gap between the electoral turnout of the richest and poorest groups.

The return of high concentrations of income and wealth, both nationally and globally, has also helped to drive global warming. The richest 10% of the global population emitted 48% of all global emissions in 2019, while the poorest 50% emitted only 12%. The top 1% emitted a staggering 17% of the total.

The outcome of the pro-rich, anti-poor strategy has been the return of a form of luxury capitalism last seen in the Victorian age, with extreme affluence alongside severe social scarcity.

Contrast Britain’s underinvestment in (for example) children’s services, young adult training, social care and affordable homes with the surging demand for private jets and luxury yachts and even mini-submarines. Private airports are big business these days. Scarce land that could have been used to tackle a chronic shortage of affordable social housing has been swallowed up by top-end property investment that serves no social purpose.

Liz Truss’s agenda looks like the 1980s all over again – more inequality, more poverty and a return to fairytale economics. Such an agenda has been proved wrong once and will be proved wrong again, but not before even more economic and social self-destruction has occurred.

The economic priorities today should be the building of a fairer society by tackling the widening wealth and income gap. We need a strategy that will lift many more out of poverty, end excessive levels of corporate extraction and give a greater emphasis to meeting unmet social needs by rebuilding a weakened social state.

More of the same is not the answer to today’s mounting economic and social problems.

Support us and become part of a media that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over.

Be the first to comment