The remarkable power that supermarkets exert over their suppliers. Mainstream thinking about monopolies and market power minimises such issues, reducing them to questions of “consumer welfare” and the economic efficiency of corporations. The harder supermarkets squeeze suppliers for lower input prices, this reasoning goes, the more ‘efficient’ and the better for consumers, and it will all come out happily in the wash. To put it crudely, if we get cheap steaks, who cares if farmers get screwed?

Counterbalance is a newsletter from a new anti-monopoly organisation, the Balanced Economy Project

Cross-posted from Counterbalance

To subscribe to The Counterbalance click Here

The list of secret demands

Have you ever accidentally knocked a glass bottle off a shelf in a large supermarket and smashed it – then felt a little bit relieved, guilty and grateful that they didn’t charge you? Generous people, these supermarkets, you may think.

They aren’t necessarily that generous, though, because it may be that the supplier of that merchandise, not the supermarket chain that owns it, that must pay.

This “Breakage Allowance” is just one item – Item 14 – on a list of 40 conditions that dominant German supermarkets like Edeka, Rewe, Lidl, Kaufland and Aldi impose on their suppliers, typically small or medium-sized businesses. The list, compiled by Marita Wiggerthale at Oxfam in Germany, was quite an achievement given the fear of speaking out. If a supermarket gets annoyed with a supplier – especially one whose products are easily replaced – they can wipe out their business.

This fear of the monopolist is all about power – a concept that competition authorities struggle with, given their heavy focus on consumers. Once you start investigating monopoly, you’ll find this fear all across the business landscape.

The Power List

Many suppliers face an Alice-in-Wonderland world of extortionate demands from supermarkets. Here is one:

That means that the supplier has to make a general payment to the supermarket chain – for selling the supplier’s goods. That is as bizarre as it sounds. It might as well demand a payment “because the sky is blue.”

There are several like this, in fact. Number 31 requires the supplier to pay a “birthday bonus” to the chain when the supermarket wants to use an anniversary milestone for marketing purposes. Number 34, the “marketing lump sum,” forces suppliers to pay the supermarket chain’s marketing costs, even if the supplier’s products are not advertised. Number 35, “central remuneration” insists that the supplier makes a payment as a percentage of sales “for the supermarket chain to organise its (own) purchasing centrally.” Number 38 demands that suppliers pay for the supermarket’s Payback Card customer loyalty system, even if the supplier isn’t featured in a promotion. Number 40 charges a lump sum for the supermarket listing the supplier’s products.

And so on. These items, which basically get the suppliers to pay the supermarket’s costs, are troubling enough. Some are darker.

Number 15, for example, “Political Partnership,” makes the supplier pay the supermarket chain for its costs of lobbying government. Or try Number 27: the “Hochzeitsbonus” or “Wedding bonus.”1 After a takeover, the supermarket chain forces the supplier to contribute to the associated costs of merging two companies – which will obviously increase the power to hurt the supplier. When competition authorities approve mergers, they typically argue that merger “synergies” lower costs and are good for consumers. These particular “efficiencies” come from suppliers paying protection money.

Before moving on, look at Number Three: the Open Book Demand.

“The supermarket demands that the supplier unilaterally discloses their costing – in the name of trust and transparency. But when the supplier does so, the retailer uses this against him by claiming that “they can still do better”, that individual components of the calculation should not be taken into account, or that the supplier could still save some money.”

This seems, to put it crudely, rather like a license to keep the supplier as close to the breadline as possible: if the supplier has ‘fat to cut’ (which from the supplier’s perspective means a decent living to be made) this ‘transparency’ lets the supermarket chain identify it and potentially take the fat for itself. “Transparency and trust,” it seems, flow in only one direction.

Each condition only applies to some suppliers, but all face a ferocious regime – smaller ones especially. Oxfam summarised what they heard:

“The supermarket chain specifies its margin as non-negotiable. It haggles over every millicent, even with satisfactory margins of 40 to 50 percent. Conditions are pushed through ruthlessly. According to the suppliers, demands for conditions are never withdrawn, even if the stated reason for charging them no longer applies. Instead, new ones are added every year. In the end, the supplier is given the choice of reluctantly accepting the supermarket chain’s conditions or being de-listed.”

It’s not just Germany, of course. This 2021 report from the U.S. National Grocers Association outlines (pp9-14) a range of similar tactics, plus several others. In some cases, the reported noted, wholesale price offered to independent grocers can be higher than the retail price of a large supermarket.

In the United Kingdom, a 2008 official inquiry detailed (Appendix 9.8) a list of such abusive practices including retrospective price changes, payment delays, and more. A Groceries Code Adjudicator was set up, tasked with tackling abusive practices, but as the trade NGO Traidcraft notes, its remit is narrow and it does not cover the smaller producers. Such practices are undoubtedly widespread: in lower-income countries, where competition authorities are weaker or non-existent, the potential for abuse is higher still.

Contagious monopoly

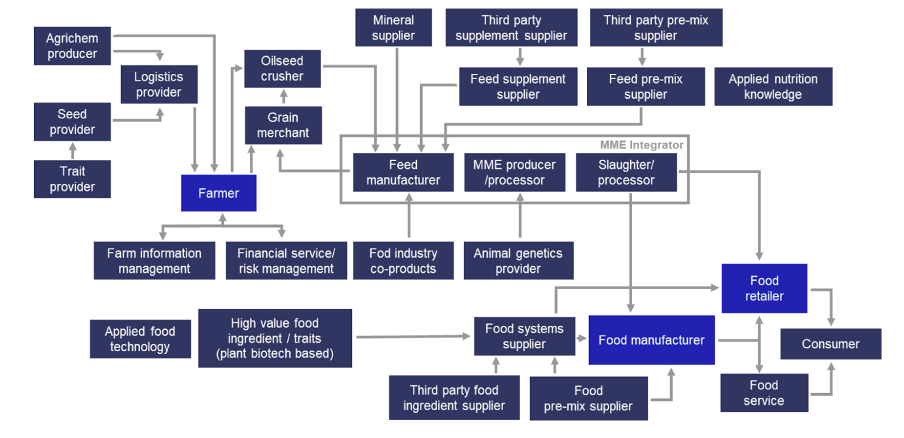

So far, we have talked of a simple world of “suppliers” and supermarket chains. Reality looks a little more like this:

As a node (or set of nodes) gets monopolised, players in adjacent nodes lose relative power, so they bulk up and merge, in response. As Moore Stephens puts it: “The principal response behaviour in the supply chain to the power held by dominant retailers, is to scale up operations.” Bigger players with irreplaceable brands can and do withstand some of this predatory activity: but one such seller, who would not go on the record with any details, still described the relationship to us as an ongoing fight.

So, monopoly is contagious. It is made worse by the “waterbed effect”, where suppliers compensate for their enforced payments to the big chains by worsening the terms for less powerful buyers like small grocery stores, thus driving still more of them out of business. The tax system can tilt the playing field even further: our second newsletter described one tax advantage rapidly wiping out swathes of UK small businesses, with government acquiescence.

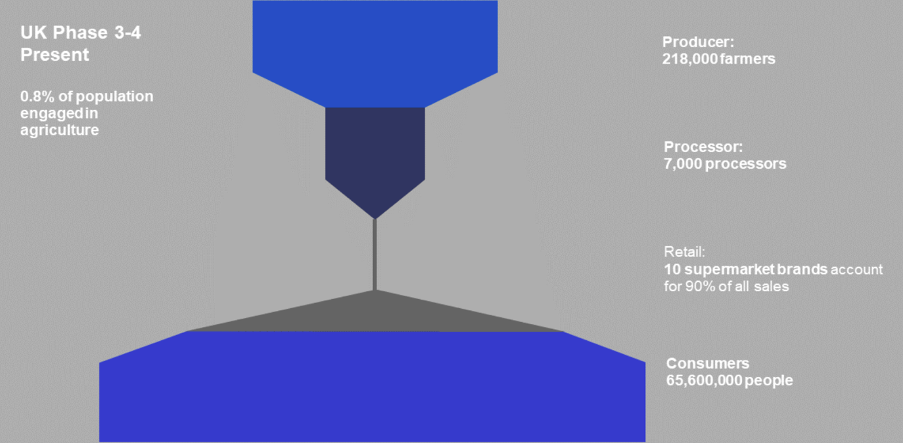

Among the nodes and connections in the food chain there are choke points – and these are where the money wants to be. We found a good image of a choke point.

Grip that thin part of the hourglass, and it’s a bit like controlling the Panama Canal. You become a gatekeeper, a toll keeper, with awesome potential for profitable abuses – just the kind of behaviour the Oxfam report highlights.

A report in Germany’s Süddeutsche Zeitung in 2016 gave an insight into how valuable these purchasing chokeholds can be, in an article about the supermarket giant Edeka’s takeover of Kaiser’s Tengelmann. The latter owned many loss-making stores in former East Germany, and the article wondered why Edeka wanted to spend 250 million Euros on KT’s 400 stores, some considered “unsellable,” and why it steamrollered the objections of the competition authorities to get them. Why play such hardball?

The answer was “purchasing power” – power to extract concessions from suppliers. If Edeka could boost its purchasing power by just one percent on 30 billion Euros of purchasing volume, that would earn it 300 million Euros a year, allowing this acquisition to pay for itself in less than a year. In reality, though, the purchasing power difference between Edeka and KT was 7-10 percent, as Tengelmann’s owner admitted. The article added:

“Edeka only has to pay the price for the merger indirectly. It is primarily paid by the suppliers and manufacturers in general, especially in the respective regions.”

Similar distortions are evident in the UK. The UK’s Competition Commission estimated in 2008 (p88) that smaller wholesalers paid 8 to 9 percent above the mean for their input prices, while the four giants paid 4 to 6 percent less. That is a staggering difference: imagine trying to compete on that playing field, and make a decent living.

Have reforms since then improved matters? People in the competition community tell us that the groceries code in the UK works well. But does it really? Do these abuses affect you personally? We’d love to hear from you.

The effect on farms, communities and high streets

As the Süddeutsche article notes, suppliers are often regional or even local businesses, but supermarket profits and dividends are received by owners, with the benefits geographically concentrated in richer regions, overseas or offshore. So these abusive practices will tend both to redistribute the national “pie” upwards from poorer to richer regions, and also to shrink the national pie, as wealth sluices out to owners / shareholders and their asset holdings overseas and offshore.

How big are the effects of market power in ‘leveling down’ our regions? We only have scattered indications. Duncan Swift, a British retail expert, estimated “conservatively” in 2014 that these direct supplier contributions alone were worth some £5 billion a year to the top four supermarkets in the UK. (A BBC report on the situation also found that suppliers “were too afraid to speak publicly for fear of being dropped by the big supermarkets.”)

Data from the U.S. is alarming. A report by the National Grocers’ Association found similar abuses of suppliers by large supermarket chains, where buyer power is often even stronger. Nine out of ten Americans live within 10 miles of a Walmart, and in many U.S. regions the retail behemoth has a market share of over 70 percent. In 2014 the ratings agency Fitch estimated that supplier payments in the United States were equivalent to a staggering eight percent of the cost of goods sold. Researchers talk of a “Walmart Effect” that depresses economic activity when a Walmart store opens. (An “Amazon Effect” may be bigger still.)

Farmers’ share of the U.S. “food dollar” – money spent on food – has declined from around a third on average between 1960-1980 to less than a sixth today. Given total U.S. annual food spending today of $1.8 trillion, a back of the envelope calculation suggests U.S. farmers would earn over $300 billion more per year if they received the same share of the food dollar as they did in the 1970s. Monopolisation is one of several factors here — but it is undoubtedly the biggest. Imagine the political dividends from fierce anti-monopoly policies that stopped a chunk of that wealth from being sucked out of farm country to absent shareholders, and left it circulating locally instead.

A lot more could be said about this mess, including the effects that the retailers’ power has on food quality and safety, or on workers, or on the environment. That’s for future newsletters. But we will now draw some conclusions, and offer ways forwards.

Consumer confusions

The silent intellectual bargain at the heart of this system is the “consumer welfare” approach first popularised by Robert Bork and other ideologues in Chicago from the 1970s. As long as consumers get a good deal, this line of thinking went, we can stop worrying about things like power or good jobs, because workers and citizens are consumers too. If corporations are “efficient” (e.g. by being big, and reaping economies of scale) then the resulting surplus will be delivered to consumers and all will end well.

These ideas spread first across the United States, and then Europe, and beyond. But they make no sense, even on their own terms. Try to follow their topsy-turvy logic, and you will soon lose your bearings.

First, what does ‘efficient’ mean? Supermarket bosses may find it “efficient” to shake down their suppliers, but this does not make for a healthy, vibrant, resilient or innovative economy: the opposite, in fact. (This misunderstanding is a version of what economists call the “fallacy of composition.”) How is Item 27 — the Wedding Bonus, where suppliers pay for the supermarkets’ monopolisation — efficient? It is the opposite.

Second, if monopolising supermarkets wring the lowest prices from their suppliers, will they pass those ‘efficiencies’ to consumers? They might not: they may pass a good chunk to shareholders. Third, those consumers are also small business owners or workers – they may have just exchanged well-paying jobs for cheaper cornflakes – and because of all the inefficiencies, those cornflakes may not be cheaper either.

Third, using ‘consumer welfare’ as the primary standard for protecting suppliers is a remarkable act of semantic gymnastics. We try to protect suppliers by first looking after consumers – yet this newsletter shows how this very quest for ever lower consumer prices is what is crushing suppliers in the first place! It makes no sense. Far better to escape the consumer-first frame, and focus on protecting these businesses directly, as outlined below.

Fourth, consumer-welfare defenders claim that their beloved concept can incorporate supplier concerns2. As the UK’s Competition Commission argued in 2008 (p164), for instance, if supermarkets crush suppliers, then suppliers won’t invest, and this “will be detrimental to the interests of consumers.”

There is truth in this. But it is saying that focusing on consumer welfare means that consumers are likely to get screwed in the end anyway!

What ever did they think would happen when they let these firms monopolise?

Don’t worry, the problem is being fixed. (Or is it?)

This month Germany adopted a law implementing the EU’s Directive on Unfair Trading Practices in business-to-business relationships in the agricultural supply chain. There will be a new independent ombudsman (as in the UK) and a price monitoring body to report unfair practices to. The list of banned practices will be expanded after an evaluation.

Unfortunately, as an NGO coalition said in March, the draft law is weak medicine, too late. As antitrust expert Kim Manuel Künstner put it: “It would be easy for food retailers to work around the proposed bans.”

German authorities know there is a problem, but aren’t (yet) tackling it effectively. If there were a vibrant and organised antimonopoly movement in Europe, as there is in the United States, it might be possible to take serious steps at last.

There is one hell of an agenda to organise around here. Food and retail affect every last one of us.

Real solutions

What can be done about all this? We suggest several broad approaches.

1. Break Them Up. Breaking giant chains into pieces could re-invigorate the food system, in Germany, the UK and far beyond. Why should we tolerate such coercive power in our economies? We also love Tommaso Valletti’s related suggestion, outlined in our last newsletter, of reversing the burden of proof for mergers and takeovers by large firms – and also his paper explaining why breakup is easier than you may think. Also see the U.S. lawyer Zephyr Teachout’s new book Break ‘Em Up: Recovering our Freedom from Big Ag, Big Tech, and Big Money. It will take years to change the public and political narrative so that this can happen – but we’re confident we’ll get there.

2. Support those in fear. Victims of this private power will not speak out because of the fear. Oxfam Germany has pioneered a path for other NGOs. Trade unions could engage: in the UK alone, some 3.6 million people are employed in the food sector. This U.S. article explains why. Politicians – on the left and the right – can find enormous opportunities here to side with small businesses. Check out the recent launch of the new U.S. group Small Business Rising, fighting “to break the power of monopolies.” We need more of this energy, outside the United States.

3. Protect suppliers directly. Ban these and other unfair trading practices enabled by monopolising power. Complement this with the right kind of transparency – that is, forcing monopolists to be fully transparent about their practices. Use “bottom-up pricing” from the farmer to the consumer, not the other way around. In Spain, with the Real Decreto-ley 5/2020 that came into force in February last year requires production costs to be listed in the contract, and the contract price between producers and first buyers must explicitly cover production costs.

4. Overthrow the dominant Consumer Welfare Standard. One alternative is the “Excess Power Standard”, currently under development by our co-founder Michelle Meagher. Without noticing power we cannot hold it to account, or see how our economic systems are set up to promote monopoly. We must assess the power of firms not just to raise prices and reduce output, but also their power to externalise costs onto society; to exploit suppliers, employees and other stakeholders; and to leverage economic power into political power. Alternatives include the “Effective Competition Standard” – see the analysis by Marshall Steinbaum and Maurice Stucke here – or the “Protection of Competition Standard”, by Tim Wu, here.

Be the first to comment