The compartmentalised nature of the EU’s policy process may be undermining its impact on climate negotiations

Tom Delreux is a Professor of Political Science and Joseph Earson is a Postdoctoral Researcher, both at UCLouvain

Cross-posted from LSE Europp

Vicenza : U.S. Army photo by Jim McGee

International climate negotiations are often synonymous with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and its annual Conferences of the Parties (COPs). Yet, a variety of other international forums have over recent decades become important settings for dealing with different aspects of the broader climate crisis.

These include informal plurilateral institutions like the G20, treaty-based frameworks like the Montreal Protocol and formal international organisations like the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) and the International Maritime Organisation (IMO). Collectively, they make up the so-called ‘international regime complex on climate change’.

The international regime complex on climate change

A regime complex is an international governance structure made up of institutional forums which govern aspects of a similar issue area (here, climate change) and have overlapping membership. As Karen Alter points out, regime complexes create a governance dynamic greater than the sum of the individual forums – political dynamics in one forum can affect outcomes in another.

Hence, negotiations on international climate agreements seldom take place exclusively within the confines of a single focal forum, which is the established negotiating forum for reaching an agreement on a specific issue. Rather, non-focal forums – the ‘other’ forums of the regime complex – also matter, as they can provide opportunities to build coalitions or to prepare breakthroughs in the focal forum.

For instance, between 2011 and 2015, the UNFCCC was the focal forum for what would become the Paris Agreement. While it was decided in 2011 that the Paris Agreement would indeed be negotiated within the UNFCCC, the negotiations were on the agenda of many other forums within the regime complex in the leadup to UNFCCC’s COP21 in 2015 (such as the G7, G20 and Major Economies Forum) – and what happened in these other forums had an impact on the UNFCCC negotiations.

EU diplomacy

The other forums of the regime complex thus present opportunities for ambitious, resourceful actors to conduct additional diplomatic activities in support of a particular multilateral climate negotiation. This is the case for the European Union. As an established climate leader with a vested interest in facilitating global climate governance via multilateral agreements, the EU has developed a robust and increasingly strategic form of diplomacy to support its climate negotiating objectives.

Furthermore, the EU itself, though various strategy documents, hints at diplomatically working across the different fora of the regime complex in support of multilateral climate negotiations. Taken together, the EU’s ambition, resources, and own statements suggest that the EU is attempting to use the available forums in the regime complex to facilitate reaching ambitious multilateral climate agreements.

However, the EU’s potential to conduct such a strategic – or comprehensive – climate diplomacy across the various forums of the regime complex is undercut by its internal institutional structures that handle the EU’s involvement in various forums of the regime complex. The EU has a compartmentalised policy-making system that is principally organised by policy area (such as transportation, environment and trade). Accordingly, the EU’s positions in different forums of the regime complex are determined in separate venues that often operate in relative isolation from each other and which are characterised by a lack of communication and alignment.

For different international forums, different Council configurations, Council working parties or Commission Directorates General are the key venues for internal EU coordination. Hence, on the one hand, the EU’s track-record and ambition as a climate leader suggest a strong potential to strategically work across the different forums of the regime complex. On the other hand, its internal compartmentalisation makes such a comprehensive use of the regime complex less likely.

An empirical test

In a new study, we address how this internal compartmentalisation affects the EU’s ability to conduct a comprehensive climate diplomacy in the broader regime complex. We examine the EU’s diplomacy in the regime complex relating to the negotiation of four international climate agreements from 2015-2018: the Paris Agreement (2015, with the UNFCCC as the focal forum); the Carbon Offsetting Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA; 2016, with the ICAO as the focal forum); the Kigali Amendment (2016, with the Montreal Protocol as the focal forum); and the Initial Strategy on Reducing GHG Emissions in Shipping (2018, with the IMO as the focal forum).

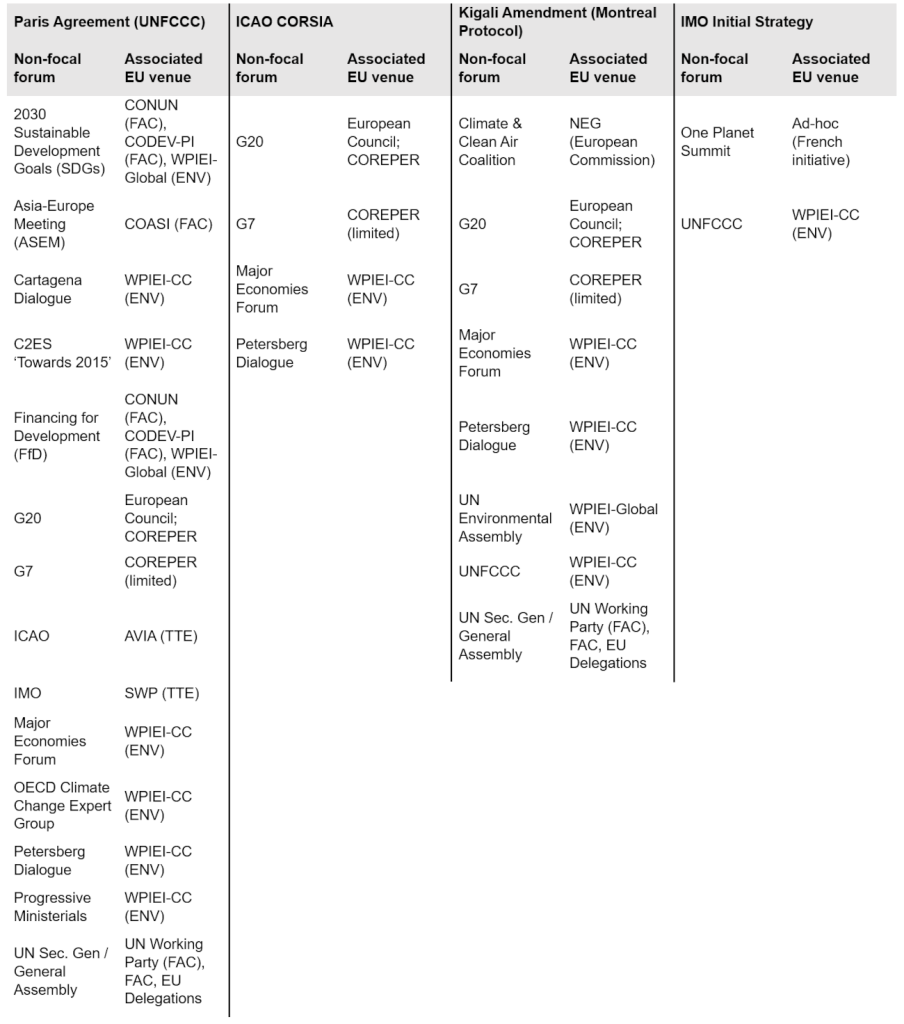

The table below presents the forums of the regime complex in which the EU was active for each negotiation, as well as their corresponding internal EU venues involved in determining the EU position for these forums.

Table: Non-focal forums for four international climate agreements

Based on a triangulation of official documents and 43 semi-structured interviews, we find that internal EU compartmentalisation in general hinders the EU’s attempts to pursue a comprehensive climate diplomacy. In other words, how the EU is internally organised limits the EU’s ability to push for its climate objectives in the entirety of the regime complex.

In the cases of the Paris Agreement and the Kigali Amendment negotiations, internal compartmentalisation restricted how the EU used the different forums of the regime complex to advocate for the main negotiations: its activities were mainly limited to building political support and consistent messaging. Conversely, in the cases of CORSIA and the Initial Strategy, compartmentalisation meant that the EU was active in hardly any forums at all outside of the main negotiating forum.

We note three important aspects of compartmentalisation that limited the EU’s comprehensive use of the regime complex. First, with the exception of the Paris Agreement negotiations, differences in priorities and policy framings between the EU venue responsible for the main negotiations and the EU venues responsible for other forums meant that it was often difficult to bring up the negotiations outside the focal forum, as the relevant venues dealt with non-climate issues and were often less interested in the negotiations.

Second, a lack of communication channels between internal venues limited the EU’s use of forums to support the negotiations. If these venues were not regularly in touch with each other, they were unable to coordinate. Third, a lack of resources within the EU policy system often meant that the EU internal venues were not closely following what happened elsewhere in the regime complex beyond their particular area of expertise, which reduced the potential for conducting a comprehensive climate diplomacy across forums.

Missed opportunities

Overall, we present a nuanced picture of the EU’s climate diplomacy and its place in international climate governance. On the one hand, the EU has attempted to use a variety of non-focal forums in support of its objectives in some focal forum negotiations. This confirms the EU is a strategic, resourceful actor on international climate issues: it makes use of opportunities provided by the regime complex. On the other hand, compartmentalisation undercut the comprehensiveness of the EU’s climate diplomacy.

The EU is clearly limited in how it uses non-focal forums because of the silos present across the different internal venues responsible for the different international forums of the regime complex. The number of forums in which the EU is active and the ways it uses them to support negotiations in a focal forum is in fact quite restricted. Given the potential for conducting a comprehensive climate diplomacy in the regime complex, compartmentalisation results in a missed opportunity for the EU and this will likely continue to be the case unless the EU can overcome its siloed policy process.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of European Public Policy

Thanks to many generous donors BRAVE NEW EUROPE will be able to continue its work for the rest of 2023 in a reduced form. What we need is a long term solution. So please consider making a monthly recurring donation. It need not be a vast amount as it accumulates in the course of the year. To donate please go HERE

Be the first to comment