Public discourse about Italy is very distorted, and we should thrive to change it

Tonia Mastrobouni is the Berlin correspondent, La Repubblica

The original article in Italian in La Repubblica is here (paywall)

Tonia Mastrobuoni (TM): Why did you start this campaign to address distorted views about Italy?

“I recently saw many wrong claims in the German-speaking media concerning Italy. I thought: if I want a change, I have to make a concrete commitment. I already did that last summer, when there was talk of the EU recovery fund – now again, as the formation of a new government in Italy was discussed; in short: with the arrival of Mario Draghi. So I thought I would tweet some data. Numbers that contradict the popular narrative of a profligate Italy living beyond its means. A problematically large part of the population in Germany, Austria, the Netherlands and other EU countries don’t know basic stuff about Italy.”

TM: Few people know that Italy has always been a net contributor to the EU budget. Or that it has had a primary surplus for decades. Why do these distorted views persist?

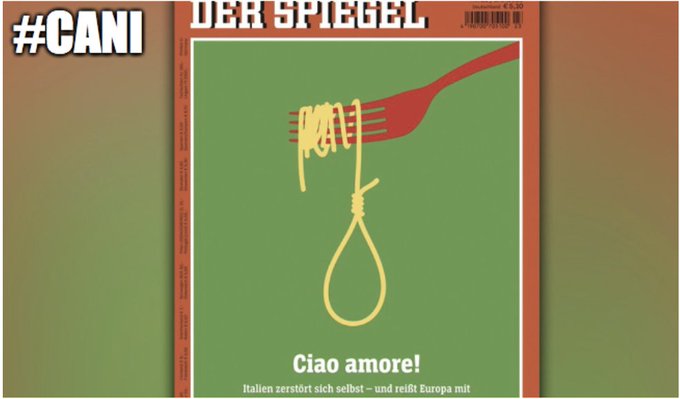

“On the one hand, I think that simplistic stories like the one about the profligate country reach many more people than facts that paint a less black-and-white picture. For example, when Der Spiegel writes yet another story about Italy destroying itself and other EU countries because it is unable to reform as some in Germany would like. It can be shown that Italy has done many of the things that continue to be pushed. But there is not yet a strong counter-narrative that can reach as many people, not least because it is a less appealing narrative. But some clichés about Italy can be refuted with data; that’s what I’m trying to do with the twitter campaign. In Germany it is indispensable.”

TM: Why?

“I think that in Germany the macroeconomic clocks work a bit differently than in the rest of the world: ordoliberalism has played an important role in economic policy and also in public opinion. This fixation with balanced budgets is very common, as is a certain scepticism about state involvement. And the widespread opinion is that Italy’s biggest problem has been a lack of fiscal discipline, even though the data suggest otherwise. But beware: this German view is slowly changing.”

TM: Yes, it is changing, especially during the pandemic. Economists like Lars Feld and Clemens Fuest were the first to say ‘we need something to hold Europe together’. From Germany came the impetus of the Recovery fund and a lot of public money was injected into the economy.

“Yes, I think the dominance of ordoliberalism is crumbling. But a lot will also depend on how the public discourse changes, and what the outcome of this year’s federal elections will be. But you can definitely say that other German economists are gaining influence, like Isabel Schnabel, the German representative on the ECB board. She has a much more international outlook than some of her colleagues.”

TM: Unfortunately, however, the “frugal” countries are reviving some false narratives about Italy.

“True. And in Austria or in the Netherlands you can’t use ordoliberalism to explain it. But the narrative of a profligate and untrustworthy Italy simply works, you can gain a political advantage in the short term. The unfortunate thing is that these divisive narratives also drive the growing political polarisation in Europe. And Italy is a favourite victim because its public debt was already higher before the pandemic than in other countries. The Germans, the Austrians and the Dutch are not wrong in saying that we need to think hard about how to deal with public debt. But the truth is also that spending cuts have been made in the wrong places, for example in the health system.”

TM: Some say that we should simply write off part of the debt. Do you agree with that?

“No. And I am not at all in favour of playing down Italy’s problems. I have often repeated it: of course Italy has structural problems. The skyrocketing public debt was mainly due to mistakes made in the 1970s and 1980s. Then, because of fiscal austerity, which had negative macroeconomic effects, it was not possible to bring down the public-debt-to-GDP ratio. Then came the financial crisis and the debt-ratio started to increase again. There are other problems, of course: stagnation, the North-South divide, dysfunctional politics, income levels lagging behind countries like Germany. I have the impression that the stagnation of the last 20 years and now this sequence of economic crises have been a breeding ground in Italy for a certain fatalism. And I think that the worst reaction from the German and northern European side is to hit Italy hard. It’s clear that large parts of the Italian population are asking themselves ‘What kind of tone is this from our partners?’ Maybe we should start to see Italy mainly as an important partner again.”

TM: Do we need something like ‘change through rapprochement’, like Willy Brandt’s famous campaign for the East, but this time for the South?

Yes. Merkel has already started with her push for the Recovery Fund. It is a significant change to commit to a large, albeit temporary, fund to ensure Italy and others can recover faster from the crisis.

TM: Perhaps dictated, however, by the awareness that a fast German recovery and a collapse of countries like Italy, after the pandemic, would again put the survival of the Eurozone at risk.

“Yes, but it’s still a big political shift. My hope is that we don’t stop there now. That the Next Generation EU will concretely contribute to Italy recovering. And that we will then proceed along this path of making European integration work. We must also hope that Italy can get rid of this fatalistic spirit, which has often been, and risks being in the future, a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Be the first to comment